For Johnny Johnson, it was always Saturday night. He was the stuff of fictional heroes who prevail over their circumstances. A British army doctor who later joined the Royal Navy, Johnny came from a broken home, never married, and eventually saw his only child given up for adoption. When he left school in the depths of the Depression, he had no prospects of a job and turned to medicine because he “thought he might meet girls there,” rather than from any burning sense of vocation. He struggled with financial worries and declining health throughout his adult life. It is possible he suffered from some form of personality disorder, or even schizophrenia.

But the world was one vast opportunity for Surgeon Lt.-Cdr. John Robb-Johnson, whom I met in early 1965, when he was 43 and I was 8. Whatever his circumstances, he always believed that the next day, or the next moment, would be better. For him, the glass was always half full; often literally so, as he consumed up to two bottles of gin per day. While he formed few close friendships, Johnny was widely popular and extravagantly generous with his time and money. People loved to hear him talk. He had a bottomless fund of stories, which sometimes became more amusing, or dramatic, over time, but which never failed to hold his audience. Among other things, Johnny had been an Olympic-class oarsman, a professional boxer, a fairground barker, a naturist, a published poet, and a sometime mercenary. When officers in the Kenyan air force attempted a coup d’état in August 1982, Johnny immediately made plans to fly to Nairobi and offer his services to the loyalist forces. A fluent Swahili speaker, he reasoned he was “just the sort of unscrupulous bugger” to help maintain the status quo, although in the end law and order was restored in his absence. As consolation for missing out on the action, Johnny went off on holiday to Northern Ireland, where one night two members of rival sectarian gangs shot each other in the pub where he was staying. I asked him what he had done. “Assessed the situation,” he said. “One of them was dead, and the other was hit in the gut. I stuck my hand in the hole and offered him a brandy until the ambulance arrived.”

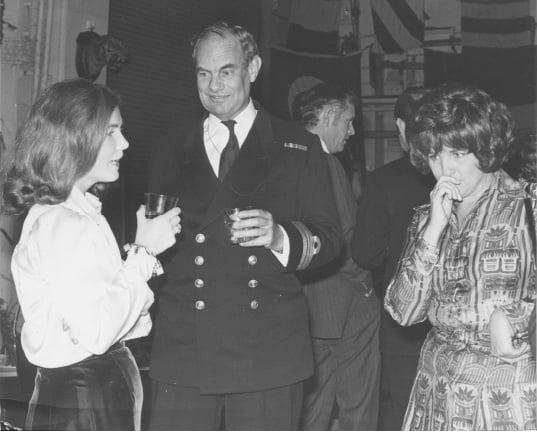

At the time I met Johnny he was a burly, broad-shouldered man who habitually dressed in grey-flannel trousers and a navy-blue blazer, in whose breast pocket he kept a monocle. After rather abruptly leaving the army, he was serving as the ship’s doctor on HMS Protector, an ice-patrol vessel commanded by my father. Protector’s core mission was to set sail each autumn for Antarctica, and to return to England the following spring. Supervising the physical and psychological welfare of a ship’s company of 250 in this most inhospitable of places proved a stern test of Johnny’s professional skills. I once asked my father how his friend and subordinate had coped. “Not bad,” he said. Then he laughed in a distracted sort of way. “Apart from the seaweed incident.”

The “seaweed incident” had come about when Protector was in some lonely spot in the South Atlantic, where Johnny had decided it was time for him to carry out a snap inspection of the ship’s food-storage locker. He was always rightly keen on maritime hygiene. In this case, something about the texture or quality of the stores struck him as “off,” although there were those who subsequently felt that it was Johnny himself who was the more impaired. Whatever the cause, the result was that Protector’s meat ration for the month was unceremoniously cast overboard on her doctor’s orders. Johnny’s substitute diet for the crew of boiled seaweed with a generous rum seasoning was, at best, imaginative and, at worst, toxic—Protector duly recorded the Royal Navy’s first confirmed cases of scurvy in over a century, the subject of a lively ministerial exchange in the House of Commons.

When Johnny separated from the navy in his late 50’s, he spent a month in Saudi Arabia tending to the needs of a large community of British builders employed on a housing complex in Riyadh. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his time in the desert kingdom ended in some acrimony. Walking home from his clinic one day, he was arrested for carrying what was described as a “mobile bar” in his briefcase, imprisoned in medieval conditions, and eventually released on order of King Khalid (or so he insisted) and deported to England. A week later, Johnny presented himself at the same recruitment agency that had placed him and politely enquired if they had a vacancy. The man who greeted him at first failed to make the connection. “Yes,” he said. “There’s an opening in Riyadh, thanks to some bloody fool of a doctor named . . . ,” and that “pretty swiftly” concluded the interview, Johnny recalled.

For the middle-aged bachelor, there was nothing remotely embarrassing or unseemly in showing affection for a young schoolboy. It was all entirely innocent, and, more to the point, it was fun. Looking back on it, it’s possible Johnny’s fondness for childish rituals like gorging on cake, watching cartoons, or what he called “rotting up” authority figures testified to the stunted emotions still warring inside the globe-trotting doctor. All I knew at the time was that I loved him as a substitute father, a figure of power and authority in the outside world, but who liked nothing more than to sprawl on the floor reading aloud from Winnie the Pooh (he once translated the story into Latin for my amusement) on a rainy afternoon. For some reason, I lost touch with Johnny between the ages of about ten and twenty. In the meantime, I discovered politics, grew my hair (those were the days), and affected the general air of a distressed motorcycle-gang member. Hearing one day that Johnny was in town, I decided to shock him by walking into the pub dressed in a black leather ensemble and a Chairman Mao cap rakishly pushed back on my head. The last time we met, I had been wearing an English prep-school uniform. When I went in Johnny was sitting at the bar with a large gin, looking completely unchanged. “Ah, Christopher,” he said. “What will you have?” We might have been chatting five minutes earlier for all the emotion in his voice. Johnny immediately assumed the role of a drinking companion, one sustained, with occasionally chaotic results for us both, throughout the rest of his life. I suppose he was lonely. Once, he wrote to me, “God, what I would give for a spotty-faced kid to take fishing.”

Upon retiring from the navy, Johnny moved back to Portsmouth, where he made several appearances before the local magistrates on various charges—drunk and disorderly, biting a policeman, taking the stage at a meeting of the local Social Democratic Party to denounce the delegates as “a bunch of Castro-loving scum.” Although denied long-term employment, he was occasionally able to stand in as a locum for other doctors. Once when driving in a specially equipped radio car to visit a patient, Johnny lost control of the wheel, skidded on some leaves, and ended up trapped upside down in a ditch. He was later found to have suffered a fractured skull. Reaching for the transmitter, Johnny calmly identified himself and told the dispatcher to send two backup vehicles, one for the original patient, the other for him. In his mid-60’s, he took up with a Portsmouth woman of about half his age, whom he had hired as a house-cleaner. She already had a common-law husband, a local judo instructor, so the situation was delicate. But Johnny was touchingly gracious when the affair ended and kept the woman’s photograph on his desk, alongside that of his departed son.

Some time later, Johnny invited me to join him to watch the annual university boat race in London. I arrived at the pub, which was hot, noisy, and full of tattooed men in their 20’s whose speech was untrammeled by the demands of political correctness. In the thick of this mêlée, Johnny wasn’t so much sitting in a chair as sprawling in it almost full-length, legs crossed, laughing and joking, the picture of self-contentment. Not for the first time, I could only marvel at his powers of social assimilation. Abandoning the boat race, we moved on to a jazz club somewhere under Piccadilly Circus, where Johnny, typically, insisted on buying everyone’s drinks for the rest of the night. In his wallet, he kept a slip of paper with a favorite quote, attributed to William Penn, which dictated his daily spending habits. “Any good thing I can do, any kindness I can show to any human being, let me do it now; let me not defer it nor neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again.” We never knew where the money came from, and found out only when the local bank starting proceedings to recover what Johnny cheerfully called a “stupendous” overdraft.

Was he for real? The general consensus was that, while Johnny might occasionally embroider the detail, his instinct for controversy, coupled with his zeal for full-bath immersion in whatever captured his imagination, put the rest of us to shame for the bounded horizons of our own little lives. He really did engage kings and heads of state in correspondence on esoteric matters of public health and thought nothing of flying to Lagos or Bombay in order to deliver sometimes unsolicited speeches on the subject. He really did have an effusively signed photograph of himself and General Zia-ul-Haq, the latter fixing him with a shark-like grin, on his wall. He really did cause a near-riot when he harangued a medical forum in Sri Lanka on that state’s abnormally high incidence of liver disease, which Johnny attributed not to the traditional alcoholic causes but to a variety of other “lifestyle” factors which, he boomed from the platform, “more properly belong[ed] to the Biblical cities of the plain.” And, finding himself in the receiving line to meet the Archbishop of Canterbury following a service of consecration at Westminster Abbey, he really did tell the Primate of All England that his sermon (somehow touching, at length, on gay rights) had been a disgrace to the occasion. I was next in line, and can still remember the look on the prelate’s face.

Probably like most of Johnny’s circle, I adored and shrank from the performance in about equal measure—delighting in the energy of excess, blanching when he unleashed one of his sometimes spectacularly tactless oratorical thunderbolts. But there was rather more to him, I learned, than his ability alternately to charm and shock. As Johnny himself observed, one doesn’t survive to posterity by being colorful. His own claim was spiritual—it was as a child of God that he asked to be judged.

The first real hint of Johnny’s faith came one night when, after listening to me interminably complain about something, he said quietly, “Shall we read Psalm 88? It covers this ground rather well.” I suppose I had then been friends with him for some 20 years. We knew that he liked to attend Sunday-morning services at Portsmouth Cathedral (handily adjacent to his favorite pub), and that he often broke into a lusty a cappella version of “Zadok the Priest” at inappropriate moments, such as on a crowded commuter train, but that was it. Judging from his surface behavior, Johnny seemed to believe that man was merely trapped in the rubble of some cosmic joke with no punch line—that “Godot,” as he’d once remarked in another context, “wouldn’t join us today.” But now I gradually came to see that Johnny’s Rabelaisian public image coexisted with—and, to some extent, defined—a singularly robust Christianity. He had no use for most of what he called the “happy-clappy” clergy. “They’re really social workers, and they sweat with embarrassment when you talk to them about God,” he said. It was the “great position” of the Church that Johnny respected, the fact that She had lasted for centuries and still provided “the only real manifesto about how to live life.” In time, I saw him apply this conviction in a number of ways, from volunteering in the cathedral kitchen, to providing unpaid medical help to the indigent. A friend remembers being at a party where Johnny’s long-suffering bank manager “rather indiscreetly told me that Johnny was having cash-flow problems. He was down to fifty pounds. The man and I talked, then he left and Johnny came over and asked how I was. ‘Broke,’ I said, ‘in mind, body, and pocket.’ Johnny immediately laughed. ‘Do you want any money? I can give you fifty quid.’” That gesture summed up the man. Without ever seeming to bear an Atlas-like burden for the public weal, Johnny was supremely generous with what he called “the few faculties” granted him, more often than not anonymously so; there are those who might be surprised even now to learn the identity of the benefactor who scrubbed the floors of their church or left a box of toys outside their back door in the dead of night.

“I may have made a mess of my career,” Johnny told me not long before he died. “But I don’t think I’ve made one of my life.” Nor do I. To me, he remains the embodiment of everything a Christian might aspire to be—charitable, compassionate, and above all utterly fearless in his refusal to accept handed-down truths. He may have been an affront to the Church’s more blue-rinse image, but Johnny’s priorities were rarely those of the world. Without God and without truth, he once said, there was only a “dull little merry-go-round of things and possessions and successes.” And the truth is, about those who were lucky enough to know him, that he changed us. I’m here to testify to that.

Leave a Reply