I returned to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) last May and July and noticed that Serbia had changed dramatically since my last visits there in late 1993. The financial reforms of a 75-year-old Serbian university professor, Mr. Dragoslav Avramovic, who has solid banking experiences in Yugoslavia and abroad, had stemmed the soaring inflation rate almost overnight. Prices had stabilized if not dropped; agricultural and industrial production had increased, the budget was balanced, and incomes, even pensions, had risen. The hard currency reserves markedly increased. Yugoslav citizens could even exchange their dinars for German marks one to one (up to 50 dinars). To avoid the printing of additional dinars to pay for the good crop (the present reserves of food could last for almost two years), Avramovic had minted large quantities of gold coins, the ducats, with gold from Serbian mines. They were accepted with enthusiasm. Instead of minting only 100,000 as originally planned, a half-million of them were to be available soon.

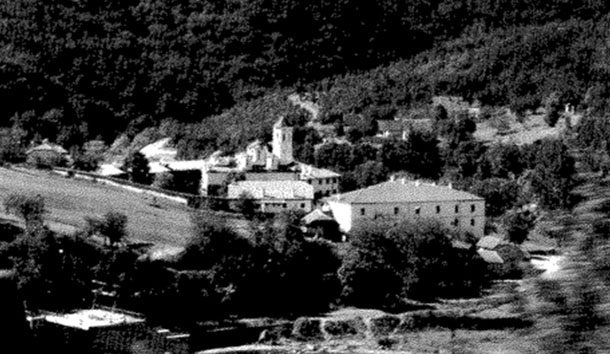

Unemployment was still running around 30 to 40 percent in the FRY, largely because sanctions had cut off the country’s trade links. But some towns were prospering, such as Vranje, in southern Serbia. Over half of its 65,000 inhabitants were employed. The giant YUMCO textile plant, one of the largest in Europe, had 13,000 employees; it imported some 10,000 tons of cotton last year alone. The SIMPO furniture manufacturer had about 6,000 workers, and the shoe manufacturers at Kostana make some five million pairs of shoes a year; the tobacco factory and the lead and zinc mines were thriving, too. These ventures make up the backbone of prosperous Vranje, whose bustling mayor Mr. Tomic is very proud of his town. The famous Serbian author Bora Stankovic was born there, and the town was alive with characters from his plays. For the spiritual heritage of one millennium, it was exciting to visit the orthodox monastery St. Prohor Pcinjski near Vranje, to stay there overnight in the old hostel, to enjoy the excellent cuisine—including the delicious trout from the Pcinja River—and to meditate and pray at the monastery.

But troubles still abound for many FRY citizens, particularly for the pensioners who worked for many years in the West. Because of the sanctions, their pensions have been blocked, and because of the restrictions on visas, it is difficult if not impossible for them to travel to the country where they worked (e.g., France, Germany, Sweden) to collect their money. They were affluent before 1992, now they depend on whatever welfare is available.

As a consequence of the successful financial reforms, the shops and supermarkets were full once again. The Belgrade cafes and restaurants were bustling, and tourism was in full swing. Most of the gas stations were still closed, with the exception of a few private ones, but hundreds or even thousands of “gas smugglers” were selling from their private stocks. The authorities do not interfere, because these men supply the fuel that the private transport system needs. Many of the smugglers were Albanians, and Montenegro, the twin republic of FRY, is flooded with less expensive Albanian fuel. Of course, most Albanians hate the Serbs, but money and greed often trump history.

The neighboring countries had long since lost faith in America’s and the E.U.’s promise to compensate them for the huge financial losses caused by sanctions against the FRY. During an international meeting of journalists in the FRY last May, the Bulgarians, Greeks, and Rumanians put their losses at four to five billion U.S. dollars each, the Ukrainians at two to three billion, and who knows how much Macedonians have lost. All of them had received only empty words and promises.

Serbs were pleased to hear from Bonn that the Nazi past of Mr. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, the former foreign minister of the German Republic, had finally been publicized. He had never forgotten the important role that the Serbs and Yugoslavia played in defeating Germany in the two world wars, and many Serbs to this day hold him primarily responsible for engineering the Yugoslav tragedy.

There was much discussion about the Pope’s planned visit to Belgrade. Most members of the orthodox clergy objected to the idea. The Vatican had too vigorously supported the secession of Slovenia and Croatia; it even beat the E.U. in its rush to recognize them. Nor has the Catholic Church ever apologized to the Serbs for the role played by many Catholic clergy in the holocaust of Serbs from 1941 to 1945 in the independent state of Croatia. During that time, some 800,000 Serbs were murdered by the Croatian fascists and their Muslim allies from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many Catholic clerics collaborated with them. More than 200,000 orthodox Serbs were forced to convert at gunpoint. There were some Catholic clerics who protected and even risked their lives to save their Serbian brothers, but other Vatican circles helped the most notorious killers to escape at the end of the war to South America, Australia, and the Middle East. This was the well-known “rats channel,” or “monastery path.” One of its organizers was a Croatian Catholic cleric, Krunoslav Draganovic, the secretary of the order of St. Jerome’s Brotherhood. Dozens of other clergymen helped him. The recent book by Simon Wiesenthal (Justice Not Revenge) recounts this story.

The availability of much-needed medical supplies and drugs had not improved. Babies and children, the chronically ill and the aged, were still dying from lack of treatment. The situation in the Republika Srpska (the Serbian part of Bosnia and Herzegovina) and in the Republic of Serbian Krajina had reached the crisis stage. Diabetics were still dying because there was no insulin and they had no money to buy it on the black market. The infant mortality rate was still rising ominously. One of the few international organizations trying to help was UNICEF.

Among the main topics of discussion in Serbia was the problem of Bosnian Serbs after the Contract Group Ultimatum. Would they accept it? Most people I spoke to said they would not, because the plan did not settle the constitutional problems of the three entities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. They believe it is impossible to have all of them in a single state or union, especially after this horrible civil war in which nobody is completely innocent. But the main obstacles to the peace agreement were the maps. Most of the Serbian people of Bosnia and Herzegovina live in its western part, where their capital city Banja Luka is located. Serbs from the Serbian Republic of Krajina are also there. They are connected with their brothers in eastern Bosnia and with Serbia by a thin corridor whose narrowest part, near Brcko, is only four to five miles wide. The Bosnian Serbs and the Serbs from Krajina opened this corridor in heavy fighting in 1992 and 1993. It is vital for their survival. Yet the Contact Group maps gave Brcko (at the Sava River) to the Muslim-Croatian federation, thus cutting the vital lifeline and leaving western Bosnia and Krajina at the mercy of, alas, hostile Muslims and Croats! It is said that this vital corridor would be replaced by a viaduct or something like one under U.N. protection, perhaps even with Russian soldiers patrolling it. But can the Bosnian Serbs trust the U.N.? Many Serbs see this as setting the stage for a possible replay of the massacres of 1941 to 1945.

The official FRY might try to persuade or even compel the leaders of the Bosnian Serbs to accept the Contact Group plan and to try to improve the maps and the constitutional arrangements through negotiation at a later date. But is this realistic? Couldn’t (or wouldn’t) the hostile European-American coalition block any and all changes favorable to the Serbs?

During a press conference, the Montenegrin Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic discussed the problems of the modern Montenegrin merchant fleet. Montenegro had possessed about 40 ships. But immediately after sanctions were imposed, many ships were blocked, mostly in Western ports. They were not allowed to leave, and Montenegro had to pay about 100,000 U.S. dollars per day to the port authorities where the ships had been “arrested.” If they refused to pay, the ships were to be confiscated and sold. A few of them were sold at auctions, at very low prices. Shipping, tourism, and aluminum mining represent about 70 to 75 percent of the Montenegrin income.

The Serbs I spoke to were still saddened and disappointed by the disinformation about them that continues to issue from the West. Why do Western media refuse to report Muslim and Croat offenses during the present official cease-fire in Bosnia and Herzegovina? What kind of stories would have been written if Serbs had initiated the offenses? The most depressing fact for the Serbs remains that they have been betrayed by their former allies, whom they considered to be close friends: the Americans, the British, and the French. How were they so easily manipulated?

When the Muslims and the Croats were killing each other during their war in 1993, thousands of Croats were fleeing their homes in Travnik, Konjice, Bugojno, etc., ahead of advancing Muslim forces, fearing reprisals. When they reached the Serb-held territories, they were treated in Serbian hospitals and then transported to Croat-held areas. During the last days of the autonomous western Bosnia (the Bihac enclave) of Fikret Abdic, tens of thousands of Muslims fled to the Serbian Republic of Krajina, seeking protection from their Muslim brothers. Did CNN, the New York Times, or Time report this?

Leave a Reply