“There is no more self-assured man than a had poet.”

—Martial

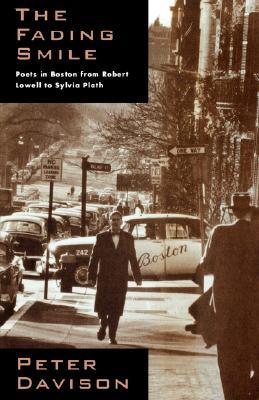

Sometimes it seems as though everyone who was anyone in postwar American poetry was attending, teaching at, or at least near Harvard in the 1950’s. This impression is confirmed by Peter Davison’s memoir: everyone was. In The Fading Smile, Davison offers glimpses into this latter-day stateside Lost Generation of American poets, a casually—we might even say coincidentally—linked group whose work would far outshine and outlast that of their Beat counterparts in San Francisco.

Davison seems uniquely positioned for such reflections. Arriving in Boston in 1955 to serve as assistant to the editor at Harvard University Press, he published his own earliest poems during this time, and later, at the Atlantic Monthly and elsewhere, had the opportunity to publish some of the best known poets of our era, including Sylvia Plath, with whom he had a brief romance in the summer of 1955. Davison was part of this crowd, though not at its center; he was on fairly close personal terms with nearly all of its members, yet—fortunately for this book—he could maintain a somewhat objective distance from them. His recollections of that half-decade and his interviews and correspondence since then with most of the key figures make for a thoughtful, revealing, yet in many ways oddly vexing study.

One strength of the book lies in its focus on this mere five-year span—in Davison’s view the critical turning point in modern American poetry. Not only were many poets on hand in Boston, but they seemed to be part of a generational shift. “Nearly all of us had had in life to struggle with our fathers,” Davison writes of his fellows, “and now our fathers-in-poetry were themselves dying.” Like the bright, rebellious sons (and daughters) they were, the younger writers consciously veered away from the forms, themes, and tones of their elders in verse.

Or was it conscious? Davison works it both ways. He disparages the prevailing “confessional” mode among these poets as “the need to prop poetry upon their bleeding flesh, . . . to insist upon their personal, beleaguered, despairing centrality.” At other times, he denies the enterprise was “a deliberate aesthetic move,” produced instead by “the nature of the era.” This may well be, of course. In his opening chapter on “The State of the Art in Boston, 1955,” and in his second, more introspective chapter called simply “The Narrator, 1955-93,” Davison compellingly evokes the Cold War tensions, tenuous material prosperity, and nascent urban decay that no doubt provided the psychic background upon which a restless, affluent generation could sketch its own frustrations. (His descriptions of Boston’s decline are especially apposite.) Though less than fair to certain poets, as we shall see, Davison’s encompassing image of a “fading smile” suggests for us a recognizable countenance of the time.

After these two overview chapters, the book is arranged into essays on individual poets—not, as the subtitle suggests. Frost through Plath but Richard Wilbur through Robert Lowell. These two represent for Davison the poles between which the other poets of the era steered. In several places Davison captures some particular nuance or gesture of a poet, not just describing accurately but indeed rendering the scene in something of his subject’s manner. We see and hear Frost in the way he “loved walking home [after a poetry reading] through the dark streets, talking his way down from the preceding high, talking his way back to earth again.” Davison’s discussions of Plath and Anne Sexton are wiser and more telling than the morose, even maudlin biographies that continue to appear, and the chapter on the late L.E. Sissman—perhaps the best section of the book—may bring some long-overdue critical attention to this neglected poet.

Unfortunately, Davison delivers these satisfactions along with so many irritations, infelicities of language, and dubious critical pronouncements that a reader may end up dismissing the entire memoir. Just a few pages in, Davison refers to the “English Louis MacNeice,” a particularly egregious error to readers of modern Irish poetry. We read that W.S. Merwin “acclimatized” (ugh!) himself to Boston, and that when he and Davison met he “spoke precisely but with confidence on a variety of subjects.” (Why precisely but confidently?) And there is this dud: “Despite their wit and ingenuity, Sissman’s early poems gasped at the deeper emotions, which other Harvard/Radcliffe poets of the time also found difficult to handle, and which the tutelage of the time, as so many poets young in the 1940’s, e.g., Maxine Kumin, Adrienne Rich, and I, would later note, tended to disparage.”

Since these poets’ activities overlapped so much, by the time we are halfway through the book we feel as if we have attended the same workshop, poetry reading, or Poets’ Theatre production a dozen times. Davison has so heavily documented the chronicle that in places it hardly resembles a memoir at all. On the other hand, it remains too subjective to be deemed scholarship. Perhaps the largest single flaw in The Fading Smile is Davison’s assumption that the “turn” in American poetry that occurred during these years was necessarily a welcome one. When he says that “American poetry in the mid-1950’s had taken a sharp turn toward the European and was due for a correction,” we get the sense that he is applauding rather than assessing the movement’s eventual impact on contemporary American verse. Thus, early in the book and apparently without irony, Davison remarks that the younger poets “might not have a great deal to learn from Frost’s poems themselves”; meanwhile, we cast a glance at Lowell’s or Plath’s literary descendants and sigh “More’s the pity.”

No poet Davison covers fares worse in this respect than Richard Wilbur, whose verbal brilliance and personal equanimity Davison finds difficult to reconcile with an era that became as identifiable for poets’ breakdowns, abortions, and suicides as for their poetic accomplishments. Indeed, Davison presents Wilbur as little more than a straw man for those who would argue in favor of raw confessionalism in poetry. Davison’s tone ranges from the softly patronizing to the blatantly envious. Even when characterizing the Confessional school in essentially negative terms, he seems to chide Wilbur for having an alternative poetic stance: “Wilbur shunned the high-profile self-expression to convey . . . the inner states of other persons, other actors, and to avoid both the private and the aesthetic dangers of self-revelation.”

Of course, Davison never explains why poems featuring “other persons, other actors” cannot be expressive of the poet. (If not of the poet, then of whom?) Moreover, this “avoiding danger” complaint merely borrows from the famous put-down of Wilbur’s early work by Randall Jarrell, whose comparison of Wilbur to a football running back who “settles for six or eight yards” indicates only that Jarrell understood sports even less than he did Wilbur.

Over and over we hear Davison’s resentment: Wilbur has been “extremely fortunate with fellowships”; his awards and honors have been “lucky for his poetry” because they have occasionally relieved him from what Davison deems an already “enviable teaching schedule.” Even worse, Wilbur has always “lived at a sanitary distance” from his academic work. (Compare this to Merwin’s “wary distance” from classrooms or Philip Booth’s “cautious distance” from Wellesley.) Wilbur’s great sin in the 1950’s, it seems, was his independence from the kind of workshoppery and poetic commiseration that marked literary Boston. Wilbur’s work did “not take a sharp turn, as Lowell’s and other poets’ did”; he had the temerity to keep “at arm’s length from the younger poets,” to “protect” or “insulate himself from the poetry world.” Wilbur says he found the Poets’ Theatre—so hallowed in Davison’s memory—”amusing but not engrossing”; long before that, at Amherst, he opted not to take the college’s only creative writing course. “I never thought I was missing anything,” Wilbur admits. And he probably was not.

If Wilbur is guilty of not needing his Boston compatriots (Davison included) to confirm his talent or revise his drafts, then Davison himself may have—albeit unwittingly—hit on the flaw at the core of our current poetry, so much of which derives from the university writing programs that are the legacy of the poetic era Davison memorializes here. The problem, of course, is that such a community cannot be manufactured or programmed—much less staffed and tenured. Late 1950’s Boston was a vortex of American poetry, as Davison ably demonstrates, one that was important, exciting, and frenetic, but also accidental and brief. As Adrienne Rich says of Harvard’s John L. Sweeney toward the end of this book, “He knew in some way that good poets come from everywhere.” Davison knows this, too, just as he should know how often the greatest talents will keep “at arm’s length” (and further) from what he admits is the “acidic turmoil of literary life.”

[The Fading Smile: Poets in Boston, from Robert Frost to Robert Lowell to Sylvia Plath, 1955-1960, by Peter Davison (New York: Knopf) 346 pp., $24.00]

Leave a Reply