Field of Blood is one of the best new novels I have read in many a year, a superbly written book by a Russian scholar and analyst who is also a careful artist, a stylist, and a poet in prose and in form who has accomplished what few essayists and nonfiction authors ever succeed at: mastering, with apparent effortlessness, the craft of fiction. Wayne Allensworth has written a fine novel worthy of comparison with some of the best American works of fiction in recent times.

The subtitle, “A Modern Western,” is Mr. Allensworth’s cue to the reader: a reference both to a literary genre and a particular geographical and culture setting, the American West. The “Western”—that pulpy concoction dating from the late 19th century and rising only occasionally to the level of real literary merit—continues to hang around, mainly on the revolving book racks placed in pharmacies and convenience stores. Its original inspiration, melodramatic, moralistic, and culturally vainglorious though it was, had some basis in reality, but one that had largely ceased to exist at about the time it was appropriated by Hollywood. Nevertheless, it lingered through the 1950’s before the revisionist and highly ideological anti-Westerns (most of them cinematic) of the next decade finished it off, save on the shelves of Walmart.

Field of Blood, on the other hand, is equally beyond the sentimental myth and the revisionist countermyth. Allensworth is concerned with (and for) the old human reality of the West that is now dead—and risen from its grave as a murderous insatiable zombie. The zombie is possessed, not by the spirit of the Old West, of the frontiersman, the cattle rancher, the cowboy, and the Texas Ranger, but by the demons of a New West that has wholly supplanted the Old: a reality shaped by the postmodern realities of commercialism, globalism, and vanishing borders; of personal immorality, self-indulgence, excess, addiction, brutality, and nihilism; of secularization, cultural homogenization, urbanization, rampant technology, bureaucracy, and imperialism, militarization, and the endless wars produced by them.

Allensworth’s Parmer, Texas, on the international border is not a multicultural community. It is a town strictly divided by a recognized border as real as if the international line to the south had jumped north some miles just to certify and accommodate the local situation. In fact it is more real than the surveyed border, being more conscientiously respected. “The family” (the Mexicans) live on one side (a no-go zone for Anglos) of the new line, the whites on the other. The Anglos are represented and led by “the soldiers”: American veterans of foreign wars waged in the Middle East, Afghanistan, and other hellholes, returned to find their hometowns transformed into ghost ones by the centripetal force of the big cities and the economic, cultural, and spiritual devastation of whatever remains of the withered communities that have stayed behind. Arrived home, they discover that they have left the war in Iraq behind them only to be drawn into another war that differs very little from the former one. Between the banks of the Tigris and the Euphrates, the enemy were the Sunni troops loyal to Saddam Hussein, and assorted terrorist groups. On the banks of the Rio Grande, they are the Mexican cartels engaged in drug smuggling, torture, and murder, foreign criminals against whom the soldiers must employ the tactics familiar to them from their Iraqi tours of duty. In a home altered almost past recognition during their absence, the soldiers find continuity—even a kind of security—in resorting to the urban warfare that seems to have followed them there. War is what they know, and all they know. And having been brutalized by wars fought on behalf of empire abroad, they are comfortable fighting a brutal conflict against a different abroad that is invading their own country. Though the soldiers and the family are mortal enemies, their attitude toward each other seems almost to be that of rival football teams before a game. The conflict is personified by Sheriff Manny Rodriguez of Parmer County, who is playing both sides of the field, and his deputy, Cole Landry, former comrades-in-arms in Mesopotamia. This fact, and the apparent contradiction between Rodriguez’s ethnicity and his office, emphasizes the cultural confusions resulting in contradictions that are equally confusing. (“‘It was the old myth of the Anglo magic that did you in, amigo,’” Rodriguez tells Landry. “‘They didn’t become you. You became them. And I,’ said Rodriguez, ‘am the result of the . . . union.’”) The novel’s progressively suspenseful story builds by degrees to Parmer’s annual ritual, a symbolic confrontation on Veterans Day between the soldiers and the family that, despite its violent overtones, ends in an unexpected manner.

Field of Blood is Wayne Allensworth’s first novel. Like most first novels, it displays abundant traces—so obvious that they often seem almost like direct references—to the dominant model present in the author’s mind, which is the fiction of Cormac McCarthy. This is true of the book’s stylistic techniques, but also of its mood, its tone, its authorial voice, and the voices of the various characters. This manifestation of the texts behind the text is at once natural and inevitable. Most young, or beginning, novelists import into their first work a number of such influences (often of voice), which blend with time and experience in a unique personal style in which the early enthusiasms are difficult to detect. Unfortunately, as Raymond Chandler once remarked, a writer’s faults are easier to imitate than his virtues, a truth that is partly confirmed by this book, though certainly the strengths are there also, as well as Allensworth’s own. Field of Blood has a relentlessly portentous tone with which McCarthy’s readers over the decades are well familiar. Portentousness in itself can have its intended effects, but it does become annoying when the mood is unrelieved. McCarthy’s dark novels, from which this one takes its color, are lightened in places by comical interludes, some of them amounting almost to slapstick. In Field of Blood, however, humor never really intrudes, and the grounding atmosphere remains unembroidered. Were this a longer book, the fault would be graver and more obvious than it is here. Still, Allensworth’s text would be the richer for tonal variation and a dramatis personae more diverse in type and sounding less like one another.

However that may be, Field of Blood is a considerable literary achievement as well as an appalling prophetic vision of contemporary America, and of the modern world. I can think of no more pessimistic view bound between covers, yet the pessimism compels the reader and pulls him in rather than putting him off. This is a true, and terribly beautiful, novel by an artist of considerable ability. Mr. Allensworth reports that he is well started on its successor. It deserves to be anticipated with eagerness.

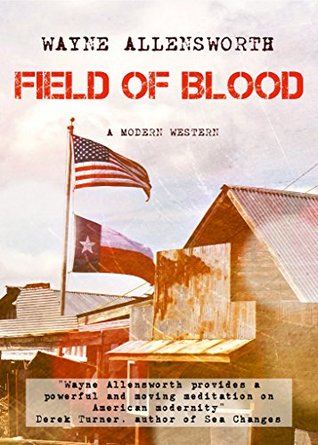

[Field of Blood: A Modern Western, by Wayne Allensworth (London: Endeavour Media) 213 pp., $7.99]

Leave a Reply