At the Crossroads

by Justin Raimondo

“No one is free save Jove.”

—Aeschylus

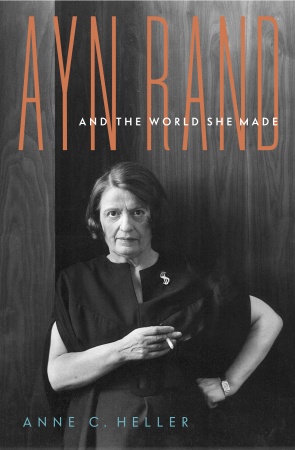

Up until now, Ayn Rand hasn’t had a biographer worthy of the name: only the memoirs of embittered ex-followers, or hagiographies written by devotees. Anne Heller’s Ayn Rand and the World She Made remedies that lack. It’s the first serious attempt to get behind the ideologue and catch a glimpse of the woman. Not that there aren’t a few problems . . .

Born in Russia in 1905, Rand, the middle daughter of a well-to-do pharmacist, was swept up in the turmoil of the Bolshevik Revolution, and one of the persistent themes of Anne Heller’s book is that this was the formative influence on her life and the development of her philosophy. While early experiences can have an outsized impact, Heller overplays this angle. For example, she tries to make the point that Rand’s Jewish heritage made her an outsider in Russia, and that because pogroms were sweeping the country as she was enduring her difficult girlhood, her reaction to rampant Russian antisemitism was the genesis of her philosophical outlook and literary method, which elevated outsiders to the status of heroes. Yet Rand never said a word about such struggles, and the historical record tends to contradict Heller: The Whites led the pogroms, as the proportion of Jews in the Bolshevik Party was a mainstay of their propaganda. Yet Rand and her family fled to the White-held Crimea, only returning to St. Petersburg after the Soviet victory.

Heller, who had no access to the archive of materials jealously guarded by the Ayn Rand Institute, has nevertheless done her research. Her book describes Rand’s youth in Russia with an impressive precision and attention to detail. Yet Heller tends to blow small incidents out of proportion. She describes an occasion when Rand’s mother, a vain and difficult woman, denied her a midi blouse and forbade the drinking of tea, considered too adult for a child. From this, Heller concludes,

The elaborate and controversial philosophical system she went on to create in her forties and fifties was, at its heart, an answer to this question [“Why won’t they let me have what I want?”] and a memorialization of this project.

Rand was no more than five years old at the time—yet we are expected to believe that she developed an entire worldview out of this incident. Though Heller dots her book with similarly amateur psychological diagnoses, the effect is not fatally disfiguring: She does an excellent job of documenting Rand’s early influences—including the decisive role played by her father—and shows how her unusually strong sense of self transcended the crumminess of revolutionary Russia and gave her the self-possession to defy the dreary spirit of the age.

Rand dreamed of going to Hollywood and writing for the movies, and once she managed to get out of Russia—just before the Iron Curtain fell—the movie industry was to be her bread and butter until the success of The Fountainhead in 1943. She worked for Cecil B. DeMille and was hired by the wardrobe department of RKO—just in time for the stock-market crash of 1929. Rand considered herself lucky and drove herself—with that force of sheer will which animated her characters—churning out a steady stream of short stories and movie scripts that went unsold.

Rand was nothing if not persistent. Her first sale, “Red Pawn,” tells the story of a woman who signs on to become the mistress of the commander of a Soviet prison because her husband is incarcerated therein. As the plot unfolds, the commander discovers the meaning of what it is to love something other than the proletariat. “Red Pawn” was never produced, but the money allowed her to quit the wardrobe department: She was now a full-time writer.

She found more success with a play, The Night of January 16th, a courtroom drama in which the jury was chosen from the audience. Based on the trial of Ivar Krueger, the Bernie Madoff of his time, the play manages to romanticize a con man who embodies the Nietzschean values that were still part of Rand’s Russian baggage.

The same spirit pervades her first novel, We the Living—the story of one young woman’s fight to preserve her soul against the soulless prison house of Soviet Russia. It is “Red Pawn” fleshed out, yet another romantic triad in which the girl rents herself to a Soviet official in order to save the man she loves. A friend sent her manuscript to H.L. Mencken, who liked it but warned an incredulous Rand that the anticommunist slant would make it virtually unpublishable. She could hardly believe the virus that had victimized her family in Russia had followed her to America.

We the Living, published in 1936, received a lot of attention for a first novel—which, as Heller points out, contradicts the starving-artist-overcomes-indifferent-world myth promulgated by Rand and her followers. Praised by the Washington Post and the Herald Tribune, panned by the pro-Soviet New York Times and The Nation, the novel made a name for her among conservatives.

It also made her a name among American leftists, who dominated Hollywood. When Rand sought work as a screenwriter, she ran into a brick wall. “She talks too much about Soviet Russia,” one industry insider told her agent. Blacklisted, Rand stepped up her anticommunist activities, lecturing and giving interviews. Heller avers that this doomed her efforts to bring her family to America, and her correspondence with them ceased: She didn’t want to endanger them.

A stage adaptation of We the Living and another play went nowhere, but Rand—who, in her journal, vowed to turn herself into “a writing machine”—was undeterred. She began the novel that was to make her famous: The Fountainhead.

The Fountainhead is the story of an architect, Howard Roark (very loosely based on Frank Lloyd Wright), who wants to build his buildings his way. Here, again, Heller raises Rand’s ethnicity to center stage, contending that Roark’s psychology is a perfect reflection of “the Eastern European Jew”—an argument made no more convincing by repetition. Heller is on steadier ground when she drops the antisemitism trope and traces the distinctively Russian origins of the book, noting that

in Roark-land, as in Russia, production is prized far more than its cousins accumulation, acquisition, and pleasure: no good character . . . wants anything material or relational for himself, and even the bad characters’ deepest ambitions are spiritual.

Rand practiced what she preached. Her novel unfinished, and her money running out, she signed on as a volunteer for the presidential campaign of Wendell Willkie.

A more unlikely champion of Randian values could hardly be invented. Rand, however, insisted on projecting her values and ideas onto anyone who caught her fancy. She was, after all, a fiction writer. She threw herself into the campaign, speaking on street corners, and befriended Mencken, Albert Jay Nock, and other Old Right stalwarts. When Willkie lost and then went over to the New Deal, Rand and her confrères organized the “Associated Ex-Willkie Workers Against Willkie,” an organization devoted to exposing the former candidate as a tool of the U.S. Communist Party. She decided it was time to form an organization dedicated to advocating a consistent defense of capitalism and individual rights and, in the process, met Isabel Paterson, book editor at the New York Herald Tribune. A committed libertarian with a reputation for prickliness, the widely read Paterson instructed the Russian émigré in American political theory and history, effectively Americanizing Rand’s evolving philosophy. “She was clearly modifying her earlier Nietzschean belief of the native superiority of the best . . . relative to ordinary men, which permeates her writing of the 1920s and 1930s.” Pointing to the first edition of We the Living, which is filled with Nietzschean turns of phrase cut from subsequent editions, Heller avers, “In America, heroes are made, not born.” The mature Rand would emphatically agree.

Meanwhile, The Fountainhead still had not found a publisher, and Rand’s agent was getting peevish: Maybe she needed to rethink the character of her main hero, who, the agent said, lacked internal conflict, the essential ingredient of a good fictional creation. Rand was horrified. Roark’s stylized consistency was the whole point. The author-agent relationship ended.

In the spring of 1941 Rand was without literary representation and a job, The Fountainhead was unfinished, and her money was nearly gone. It was at this point that a savior appeared: Richard Mealand, head of Paramount’s New York office. He and Paterson went to bat for The Fountainhead, and an editor at Bobbs-Merrill, Archibald Ogden, made the book his cause: When his boss vetoed it, Ogden threatened to resign, and a contract was signed. Rand engendered antagonism from the intellectuals but also inspired champions whose zeal made up for their lack of numbers.

The Fountainhead, an American classic, requires a plot summary no more than does Huckleberry Finn. Suffice it to say that the climax of the novel, in which Roark blows up his own building because its original design has been altered, limned the impact Rand made on the critics, and the public at large. In a typical review, Diana Trilling managed both to miss the point and to underscore her own incomprehension, writing in The Nation that The Fountainhead was written as “a glorification of that sternest of arts, architecture,” likening it to communist-inspired “proletarian” novels and declaring that “anyone who is taken in by it deserves a stern lecture on paper rationing.”

There were some good reviews, but initial sales were slow. In the fall of 1943, however, sales started to climb, and Bobbs-Merrill initiated a new publicity campaign. By the end of the year, the book had sold 100,000 copies, Warner Brothers had bought the movie rights, and Rand had been hired to write the screenplay. She and her husband moved to Hollywood, where she bought a house such as Roark might have built, designed by the modernist architect Richard Neutra.

She was at the top of her artistic form and had reached the pinnacle of success: Now began the descent into didacticism. Instead of turning to her next novel, she began work on a nonfiction presentation of her views, with the unpromising title The Moral Basis of Individualism. Heller informs us that “she found expository writing boring and difficult at this stage in her career,” and the project was aborted. But was it?

Atlas Shrugged, her magnum opus, has all the elements of a thriller such as Rand might have written in her youth: drama, colorful characters, and the kind of tension that she had hoped to bring to her stage plays but never quite succeeded in achieving, except in novel form. It also features long philosophical speeches, including one that goes on for 50 pages, in which the hero starts with the axiom “A is A” and winds up his stem-winder justifying laissez-faire capitalism, going from metaphysics to epistemology to ethics and on to political economy along the way. Rand managed to get away with it, but just barely. At times, the dry didacticism nearly overwhelms the extravagant romanticism that is her hallmark as a writer in the tradition of Victor Hugo and Edmond Rostand. The Americanization of Ayn Rand, the shedding of her Nietzschean and Russian literary-intellectual roots, sent her on a path that would lead, in the end, to artistic sterility—the end of her career as a novelist, and the beginning of her career as a cultist.

She received thousands of fan letters, one of the most impressive from 19-year-old Nathan Blumenthal. They soon engaged in a correspondence, which led to a meeting—and the rest is tabloid history. I won’t go into the details of the affair that ensued. The memoirs of the participants, including the caddish Branden (Blumenthal’s adopted name) and his wife, Barbara, have told us more than anyone needs to know. These two latched onto Rand like leeches and encouraged her to create the cult of “Objectivism”—the somewhat crankish-sounding name she gave her philosophy. Her circle of older friends vanished, replaced by the youngsters of “the class of ’43,” mostly relatives and friends of the Brandens, who, after the publication of Atlas, started a lecture organization, a publishing house, a magazine, and even a theater company centered around Rand’s ideas.

She never wrote another word of fiction. Instead, she devoted herself to “the world she made,” as Heller’s title suggests: a narrow, cramped, cult universe, from which she gradually excommunicated all but the most slavish.

A good half of Heller’s book is devoted to the antics of many people who called themselves Rand’s disciples, and they were nothing but trouble in the end. Rand should have remembered her Nietzsche:

When Zarathustra had taken leave of the town to which his heart was attached . . . here followed him many people who called themselves his disciples, and kept him company. Thus came they to a crossroad. Then Zarathustra told them that he now wanted to go alone: for he was fond of going alone.

[Ayn Rand and the World She Made, by Anne C. Heller (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday) 592 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply