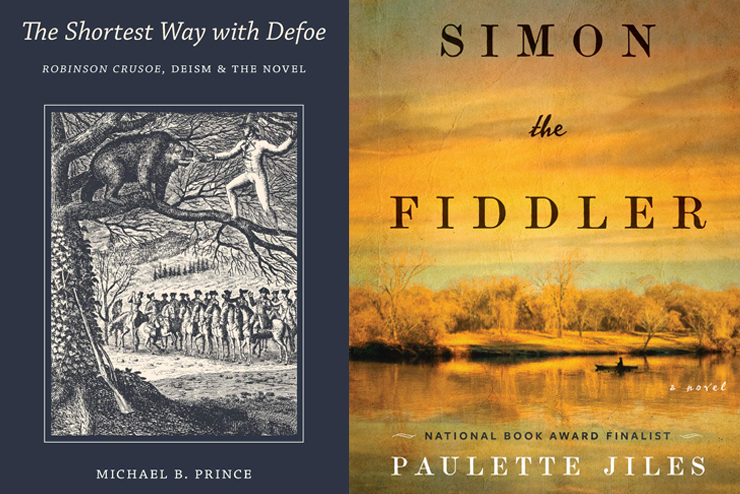

The Shortest Way With Defoe—Robinson Crusoe, Deism, and the Novel, by Michael B. Prince (University of Virginia Press; 350 pp., $69.50). Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel A Journal of the Plague Year has been much-read recently, for obvious reasons. But of course we remember him chiefly for 1719’s Robinson Crusoe, which was immediately popular for its new, realistic style, and because its hero was an idealization of English resourcefulness abroad during a period of overseas expansion. Boston University’s Michael Prince proves there is yet more to this formative work. His literary sleuthing shows how Defoe used Crusoe to perpetuate a long-running private, political grudge, and to convey a then-dangerous deism.

Defoe was born Daniel Foe circa 1660 to a nonconformist London family. He became at different times one of the Duke of Monmouth’s rebels, a soldier for William III, a Whig and a Tory journalist, a brilliant satirist, and a government spy. He was called “a Scandalous Pen, a foul-Mouthed Mongrel,” pilloried for seditious libel by one government, and convicted of treasonable publication by another. He wrote on anything from the supernatural to trade, poetry to topography, morals to foreign policy, and he published over 500 works during his lifetime. Privately, he was plagued by bankruptcy, debt, and the deaths of six children.

Defoe feuded with gusto. Among his bitterest enemies were High Anglicans and Tories angered by his 1702 hoax pamphlet, The Shortest Way With the Dissenters, which took High Anglican arguments to ludicrous extremes. Prince threads expertly through a fascinating period when English journalism was beginning to bud; over 300 periodicals were launched between 1700 and 1720. He traces Defoe’s journey from experimental writer and innovative editor to novelist of measured verisimilitude. He squirms to see what he calls the “cosmopolitan” Crusoe of the earlier books becoming “an embarrassment…a clichéd colonialist, religious fanatic, and racist” in the novel’s sequels.

There can be no “short way” into so busy and diverse an author, and Prince can be opaque, but any stylistic shortcomings seem unimportant measured against the author’s scholarship. Defoe wrote that Crusoe was a tale told with “modesty, with seriousness, and with a religious application of events…” Something similar could be said of Prince’s contribution to a better understanding of a fascinating and important person, and of the world-changing culture of his island nation.

(Derek Turner)

Simon the Fiddler, by Paulette Jiles (William Morrow; 352 pp., $27.99). To her credit, Paulette Jiles does not mind ignoring the credos of social justice in her new novel, which is set at the close of the Civil War and during the early years of Reconstruction. Simon the Fiddler is more concerned with real justice. It is also distinguished from much of American fiction so far this century by being fit to read and worth reading.

Simon is chiefly set in Texas during the conflict, destruction, and disorder of this period, which amounted to an occupation and the continuation of the war in a new phase. Jiles, a Missouri native and National Book Award finalist, has lived in and outside San Antonio since the 1990s. Simon is reminiscent of John L. Mortimer’s Song of the Pedernales: A Novel of Reconstruction Texas (1975), which also takes place around San Antonio as well as in the Hill Country during the same time period.

Historical novels written about the 1860s are abundant but often clichéd, especially when televised. They include William Faulkner’s The Unvanquished (1938), Grace King’s The Pleasant Ways of St. Médard (1916), Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), and Margaret Walker’s Jubilee (1966). Stark Young’s So Red the Rose (1934), made into a motion picture, is unfortunately obscure and overshadowed by Gone With the Wind (1939). In today’s political climate, and under the influence of liberal, revisionist Civil War historians such as Eric Foner, those older works by white writers are considered noxious.

The historical novel is a somewhat motley genre devised by early 19th century writers. To be conscientious, historical novelists must fairly examine and assess the milieus and actions of the past, then illuminate them imaginatively. Retrospective views may, however, be strongly colored by the present; literary selection inevitably entails preferences and interests. Such ruling mantras as “toxic masculinity” and “white privilege” would be anachronisms but might be honored by other writers.

Thankfully, Jiles ignores them in Simon. She does not depend upon profanity and foul language to suggest her characters’ anger, contempt, or ignorance. Nor are there sex scenes, nor gender experiments, mutilations, threesomes, or other unnatural acts. Most principal characters are worth knowing. They see meaning in their own lives and others’ and they pursue worthwhile goals familiar to us—such as staying alive in a dangerous conflict.

The hero of Simon, his companions in distress, the woman he loves, and many others are kind, loyal, and basically wholesome. Those adversaries who, through jealousy or other animus, threaten and oppose them may be powerful, calculating, even wicked—or simply petty—but they are not perverts.

In short, Simon is not marked by a hostility to traditional morality and the consequent pursuit of transgressive acts and moral revolution that characterize much of the fiction preferred by magazines like The New Yorker.

(Catharine Savage Brosman)

Leave a Reply