All of the enchantment of the violin and its repertory, the provenance of Russia and specifically of Odessa, the pedagogy of Leopold Auer (who also taught Jascha Heifetz, Efrem Zimbalist, and Toscha Seidel), and decades of international celebrity—that’s a lot in common. But these books, one about Mischa Elman and one by Nathan Milstein, are in no way a matched set. They don’t even belong on the same shelf.

Allan Kozinn’s study of Elman gives his subject the benefit of research, knowledge, and perspective. Mischa Elman (1891-1967) was a child prodigy who emerged from a humble background to achieve towering success in only a few years. By 1904, he had made a successful Berlin debut. In the next year, he caused a sensation in London and was asked to play for the kings of England and Spain. At the age of 17, Mischa Elman was already “the king of violinists”—but not for long.

He was soon to be the victim of a

famous witticism—one that marked a sea cliange of style and performance practice. Elman attended the Carnegie Hall debut of Jascha Heifetz (October 27, 1917) in the company of the eminent pianist Leopold Godowsky; and when Elman remarked “Isn’t it awfully hot in this hall?” Godowsky replied, “Not for pianists.” The humor of that anecdote has masked its reality; and in a sense, there is the theme of Kozinn’s volume. Though Elman had earned the respect of Auer, Joachim, and Ysaye—that is to say, the blessing of the 19th century—he was made to seem “old-fashioned” by the aggressive and brilliant Heifetz, just as the world was shaken up by the First World War. Much of the sweetness of life, in the form of flexible tempi, beautiful sonority, and personal expressivity, was blasted away as music absorbed mechanical imagery, the industrial ethos, and modernist assumptions.

When the smoke cleared, the strict and streamlined approach of Arturo Toscanini displaced the more freely breathing and manipulative styles of Mengelberg and Furtwängler, among conductors; and among pianists, Arthur Schnabel’s aristocratic approach displaced the personalized renderings of Elman’s friends Leopold Godowsky and Josef Hofmann—although Vladimir Horowitz, a grand-Romantic by any standard, did not begin his American career until 1928. But Horowitz’s Romanticism, like Heifetz’s, surely differed from the subjective interpretation that had come before. It was personal and individual; but it was also glitzy, highly polished, and modern.

The difference between Elman and Heifetz can today be vividly demonstrated by comparing their early recordings of the Tchaikovsky concerto, both conducted by Barbirolli—Elman’s of 1929 (available today on Pearl GEMM CD 9388, imported by Koch International) and Heifetz’s of 1937 (formerly on a Seraphim LP, 60221, if you haven’t got the original 78’s). Elman is searching, soulful, and singing; the barlines scarcely exist. Heifetz is brilliant and tight; the melos is submerged beneath the passage-work.

Kozinn’s book does more than tell the story of a great instrumentalist; it uses him as an example—a salient one—of the fate of the Romantic virtuoso in the modern environment. Though he does not make the comparison, there may have been more than a stylistic difference between Elman and Heifetz; Elman was a devoted family man all his life; Heifetz died in an embittered loneliness. What Kozinn does argue, in portraying Elman in context, is that his Jewish background was decisive in determining his musical character. He sees Elman as a product of the tradition of the badchen, and other Russian, American, and Israeli violinists in that light as well. He implies, too, that Elman had an affinity with the melodic line that is highly vocal in its orientation, the same point a German critic made when he proclaimed that Elman’s performance of the Mendelssohn concerto had the quality of bel canto. As one who once had the good fortune to hear Elman play that piece, I can’t argue with the judgment.

Allan Kozinn’s biography of Mischa Elman is brimming over with information and analysis, with anecdotes and criticism, and with the sense of a musician’s life. His book includes as it should a complete discography, and gives a thoroughly satisfying account of Elman’s career in context, as well as close-ups of his personal life. Mischa Elman, who left such individual sound-images behind, deserves no less.

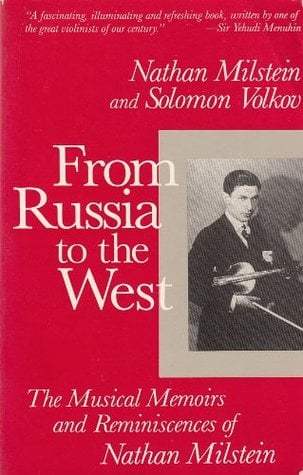

But Nathan Milstein (born 1904) has not agreed that he himself deserves such a thoughtful treatment. His reminiscences of Odessa and St. Petersburg before the war and the revolution, of Soviet Russia in the early 1920’s, of Auer and Horowitz, and of the Russian culture he misses to this day—all these have a colorful force. He continues with his stories of his western travels, an abundance of anecdotes about celebrities, and too many references to food. Perhaps Milstein’s best chapter, if it is not his treatment of Rachmaninoff, is the one on Eugène Ysäye and Queen Elizabeth of Belgium. But as the pages fly by, the realization sinks in that Nathan Milstein has no theme, no organizing idea that he wishes to impart. Although he emphasizes his Russian roots, he goes so far as to embrace his nearly stateless existence, so Russia and exile is not his theme. The violin, curiously enough, is not his theme, either. Aside from some remarks on the importance of bows, this great violinist has little to say about his instrument. And most of his remarks about the violin literature are oddly shallow: Beethoven didn’t know how to write for the violin, Brahms’s violin concerto isn’t much good, and neither are those of Sibelius and Elgar.

The one pattern I could isolate was a series of stories ending “Milstein was right!” or “Nathan, you were right!” But though many of his observations are shrewd ones, Nathan Milstein hasn’t taken the trouble to make much out of his memories, which in this form remind me of nothing so much as one of those “as told to” sports autobiographies that blight the bookstalls.

Just why Milstein would settle for so little is hard to understand. The elegant violinist of impeccable taste and musicianship would hardly seem to be the source of so much self-indulgence and triviality, and so little serious substance. But so he is. Milstein’s book is recommended for those in search of gossipy stories, memories of food, and explanations of why Nathan Milstein is great, even without his violin.

[Mischa Elman and the Romantic Style, by Allan Kozinn (New York: Harwood Academic Publishers) 405 pp., $42.00]

[From Russia to the West: The Musical Memoirs and Reminiscences of Nathan Milstein, by Nathan Milstein and Solomon Volkov, Translated from the Russian by Antonina W. Bouis (New York: Henry Holt and Company) 282 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply