Once, in a Paris bookstore, biographer Leon Edel heard Ernest Hemingway’s take on T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom. “Camels!” bellowed Papa. “Camels!” In his new book, Thomas McGuane has given us Horses! Horses!

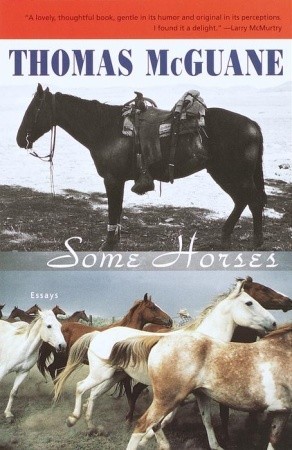

There is a theory that the artist who invests too much intellectual capital in the pursuit of sport or hobbies cheapens, or stints, his art. For 30 years—in a dozen books—Thomas McGuane has been one of the Wests foremost chroniclers of rile sweeping change and daily vagaries of life in America’s fastest-growing region. But Mr. McGuane has not published a novel since 1992 (Nothing But Blue Skies), occupying himself in the interim with the writing of essays on the blood sports and a subject close to his heart—horses. Some Horses (complete with a Cormac McCarthy-esque dust jacket) is his latest effort in this vein.

The long holiday from the demands of fiction raises two questions: Has McGuane given up on the novel as his primary form of literary expression, a form with which he has previously dazzled readers (e.g., of The Bushwhacked Piano, Ninety Two in the Shade, Keep the Change) with his virtuosity? And has he become the sort of complacent writer who slips easily into the limbo of updated reprints (three of the nine pieces in Some Horses were cut from the herd of his 1982 collection of sporting pieces, An Outside Chance)?

Some Horses is dedicated to Buster Welch, a Texan and legendary cutting horse trainer much admired by Mr. McGuane. Mr. Welch’s six-decade career as horseman and rancher is the subject of the eponymous “Buster,” in which he instructs the writer in his cabalistic equine art. McGuane’s regard for his mentor is such that he can write:

. . . an unbroke horse is original unmodeled clay that can be brought to a level of great beauty or else remain in its original muddy form, dully consuming protein with the great mass of living creatures on the planet, but a cutting horse is a work of art.

The best of the three reprints, “The Life and Hard Times of Chink’s Benjibaby” is a comic rumination on the life of a much admired, talented, and extremely difficult cutting horse. McGuane is fascinated by this mare’s cutting skill and high-strung hijinks, which include routinely wrecking stalls and horse-trailers and causing near riots at cutting horse competitions: “The first description I ever had of Chink’s Benjibaby was that she was the horse that jumped out of the El Paso Coliseum.” Another reprint, “Another Horse,” is at best an amusing piece about an elk season camping trip, rather than one about horses. In fact, horses play only a small part in the story, being—like tents, trails, and mountains just part of the scenery. The essay is a vivid paean to life in the Montana Rockies, the sort of writing at which McGuane excels, yet in the overall scheme of the book it is nothing more than stylish boilerplate.

In “Roping from A to B,” McGuane writes humorously about his days (20 years ago by now) as an amateur team roper on the local Montana summer rodeo circuit.

My own mental drill is based on advice from a fine old roper: “Remember one thing when you back your horse into the box. There are nine hundred million Chinese who don’t care whether you catch the steer or not.”

At essay’s end, the author competes in a rodeo in Gardiner, Montana, and with his partner wins the team roping event, proving that he isn’t merely a writer with “Ivory Snow hands.”

“Roanie” is the nickname of McGuane’s own “Lucky Bottom 79,” definitely a soulmate (I would guess that Mr. McGuane believes horses to have souls) to the aforementioned Chink’s Benjibaby. Roanie takes a routine trip to the veterinarian, where the gelding misbehaves and is returned home like an incorrigible schoolchild with a curt, clinical note from the vet that reads: “Lucky Bottom 79’s rectal temperature not taken as he continually endangered human life.”

McGuane is indeed fond of the cutting horse competition circuit, as he relates in “Sugar” and —especially—”On the Road Again.” In the latter story, he takes a tour with his wife, four horses, various tools and horse supplies, and some of the more necessary items for modern survival such as a microwave oven and a color TV: The “Horsabago” is a “modern farm at seventy-five miles per hour.” McGuane is good at describing the dusty suburban arenas populated by diehard enthusiasts of his arcane sport. And then there are his funny insights on hauling his 38-foot rig on the L.A. freeway system: “Oncoming traffic was pouring into my flanks from either side until I was part of a southbound general river of metal, confined in four directions to the gestalt of a seventy-two-mile-an-hour traffic jam.” Also, Mr. McGuane has a comic adventure, lying under the Horsabago and working to repair the RV’s portable sewage system, which I’ll leave to the reader’s imagination. Altogether, the piece amounts to a compelling argument for staying home and avoiding the modern multi-crazy existence of life in the fast lane. The collection closes with “A Foal,” a beautifully rendered vignette on the advent of “a new horse.”

Throughout these essays, Thomas McGuane’s prose prances and capers like a Lippizaner stallion. His next book (The Longest Silence) will be a miscellany devoted to another of his passions—fishing—whose component pieces will shine, I’m sure, like freshly caught brook trout. All well and good, but where is this accomplished sportsman-novelist’s next novel?

[Some Horses, by Thomas McGuane, Illustrations by Buckeye Blake (New York: The Lyons Press) 176 pp., $22.95]

Leave a Reply