This fine first collection of poems from William Bedford Clark, the renowned Robert Penn Warren scholar who, as the back cover announces, “abandoned poetry as an undergraduate” and returned to it “in late middle age,” is a triumph of elegant formalism. This volume—which ranges widely in form and motif, from the sacred to the profane, from the personal past to the larger cultural and historical past, from a 1680 massacre of Franciscan martyrs to the cultural chaos of the 1960’s—provides ample reason both to mourn Clark’s long hiatus from writing poetry and to celebrate his return.

I am firm in my somewhat contrarian belief that book reviews, especially brief reviews of poetry volumes, must avoid raising questions that have outlived their uselessness, or posing problems—somehow rooted in the reviewer’s tendentious preoccupation with his own craft as poet—that condemn any possible answer to insignificance. Tell the reader what’s in the book. And something about what’s not in the book. You won’t find here the all too familiar skinny pseudo-imagism stranded at the crossroads of the pictorialist impasse and confused notions of free verse, so characteristic of contemporary poetry. These poems have no right-side-of-the-page phobia, no words drifting formlessly down the far left side of the page, no disordered typographical romancing of blank space. What you will find is everything from a number of well-made sonnets in modes traditional and invented to numerous skillfully constructed poems in vers libre. And you will find an extraordinary groundedness, a poised and engaging sacramental sense of experience, as when these poems address the actual sacraments of the Church (“Passion Sunday,” and “Adoration at 2 a.m.”); and in the sense of the sacred discovered in subjects ranging from the care of lawns, to hurricanes (Katrina and Rita) and bombings (“Oklahoma City”), to family memories (“An Okie Parable”) and high-school class reunions (“Welcome Northeast High Class of ’65”). Most of these poems feel comfortably Southern, with their sense of place and sense of the past, and the unobtrusive meditation on history that informs many of the poems, the sense of how the past leans over and gnaws at the present, builds to an earned affirmation in the last lines of the book, a coda:

old ways are best, from east to west;

love’s sudden strife engenders life,

that strains for Eden, where a fountain rose.

The first poem in the book, “Blue Norther,” is the title poem and as such has a special claim on the reader’s attention. The cold wind from the north, the blue Texas norther, “swift, and merciless,” blows in at night, and breaks “the earth’s back” with its icy grip. All nature is “unprepared,” and “the earth turned in upon itself again.” Naming “the first signs of a darkling season,” the poet concludes that

Suburbia could use its Hesiod,

Its Virgil or Horace.

We have need of old wisdom,

Here along Burton Creek.

This sets the tone for all that follows, and it is not much of a stretch to see it as the emotional core, the subsumptive metaphor for the entire book. In rapid succession, we move through cold gray days where an “old man has grown too deaf to know / whose ghost whispers on the stairs” (“Sketch in Charcoal”) to “places that are bad beyond reason,” places that the “Kiowas, Comanches, the crafty Osage” passed by, places where you must “Trust the trees. / They have a thing to say” (“Plains Song”). Mowing the grass, Clark meditates in the long shadow of “the duststorm’s black wall . . . a sign in our father’s time” (“Lawncare”). There is sufficient weather in these poems to make glad the heart of a weather-channel storm-chaser hoping for a chance of tornados—and sonnets. Clark rings many changes, and even if you cannot imagine a well-made sonnet about an academic promotion and tenure-committee meeting, a room through which another kind of blue norther blows, you will find it here (“Tenure Deliberations”).

And the wind blows through the poems about “the sixties,” such poems as “Cultural History,” where “Divorce and worse / Line up behind a tardy psychedelic hearse”; and “No Lady of Shallot,” with its recurrent motif “Back in the 60s (not yet THE SIXTIES)” and its evocation of “Ruined Camelot” and the 70’s that followed and “failed to surprise: / the slow replay of a quick fast-forward.” The icy grip of the wind includes the horrors of abortion, confronted head-on by Clark in such poems as “Preventive Grace” and “Abortions.”

Halfway through the book, Clark’s formal poetic sense opens out, and the poise of his vision walks hand in hand with risk-taking (“In the Maze at Mandeville”). The symphonic variation of this brief volume startles and satisfies the attentive reader throughout. The poem entitled “2495 Redding Road” deploys a Hemingwayesque “iceberg” (since the general reader is not likely to recognize the title as the Connecticut street address of the exiled southerner Robert Penn Warren), and evokes the “place of sturdy grace” that Warren and his family made, all too quickly razed. And my personal favorite in the book, on first and fifth reading, is “The Franciscan Martyrs: New Mexico, 10 August 1680.” It is the longest poem in the book, in the most open and variable form, and it is the linchpin of Clark’s meditation on history, the past that is never past. The poet doesn’t just warn us: “It is late in the day.” He counsels us: “Do not presume to warrant martyrdom, / But prime yourself for San Lorenzo’s Day.”

I have called Clark a formalist poet. Perhaps I should clarify what I mean by that term, since in my experience—with thousands of my students in poetry classes, with thousands of readers of, and live audiences for, my own poetry—form is one of the most vexed and troublesome words and notions. The prescriptions or heuristic functions of sonnet or villanelle, of meter, line, rhyme, and stanza, do not get at the mystery of form. Poetry is a way of knowing the world, and our deepest access to such knowledge is through felt apprehension of a poem’s form. Since William Bedford Clark is best known in the academic world as a leading Robert Penn Warren scholar, it seems appropriate to conclude this review with a quotation from Warren. In his classic volume coedited with Cleanth Brooks, Understanding Poetry, the finest introductory textbook on poetry ever published, Warren asks what we mean when we use the word form and observes, “To create a form is to find a way to contemplate, and perhaps to comprehend, our human urgencies. Form is the recognition of fate made joyful, because made comprehensible.” Clark’s poems, in the profound lucidity of their contemplation of personal and cultural urgencies, possess the kind of deep form that amounts to “the recognition of fate made joyful.”

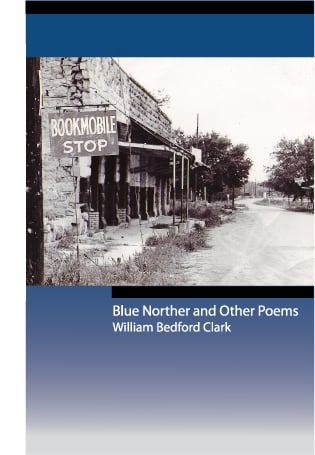

[Blue Norther and Other Poems, by William Bedford Clark (Huntsville, TX: Texas Review Press) 44 pp., $14.95]

Leave a Reply