The Ozark Mountains make up an area that American literature has largely passed by, leaving it the province of folklore and song, of homespun stories that seldom make their way to the lowlands. Ken Carey’s fine new book about the region, Flat Rock Journal, fills a great void, and not simply because with a literature so tiny it has few peers.

Deep within the briar-tangled Missouri highlands, Carey has spent the better part of the last three decades well. He has raised children without having to worry about guns, gangs, and drugs; he has fed his family largely on food that he has grown in the flourishing gardens of his 80-acre farm, fulfilling the Kentucky farmer-poet Wendell Berry’s prescription for a righteous life that too few people in our urban culture can follow. Along the way he has paid careful attention to his surroundings, contemplating the mores of the mountain people (who emerge as far more complex, and far more interesting, than the L’il Abner stereotypes outsiders have long been fed), campaigning against logging companies that clear-cut the Ozarks’ old growth forests without regard for the health of the land, and pondering the mysteries of the universe.

Carey, a born essayist, is especially good at giving us a glimpse of daily reality in the mountains; to his evident dismay, one of these realities is the ratio of reptilian to human life. “Copperheads,” he writes, “outnumber people in the Ozarks by such an extraordinary ratio that most of us hope we never learn just what it is. They are not only our most common snake, they are, in all probability, our most common animal. I killed thirty of them in the yard around our house the first summer we lived here, all within a few feet of our living area.” The argument wheels; so much killing sets Carey, who leans toward Zen Buddhism, to examine his feelings about life and death, about killing and dying. He eventually arrives at an answer satisfactory to him: “The kill-nothing philosophy is sublime. But in the Ozarks anyone exhibiting so pacific a temperament during summer months would soon be compost.” Compost is good for the tomato beds, he admits, but Carey has larger plans for himself and his family. His philosophical excursions on these and other country matters make for thoughtful reading.

Thoughtful, not somber. Carey avoids taking himself too seriously. Indeed, many of his sketches of rural life are a stitch, as a country storyteller’s tales should be, as when he recounts an exchange between two old-time dowsers arguing over where to dig a new well for his farm, “critiquing one another’s methods, concurring on some points, differing on others, arguing less vehemently as time went on, until at last, they both agreed on a spot.” He is just as good in relating his encounter with a suspicious grubstake miner who manages to keep a step ahead of the pursuing Forest Service, from whose holdings he aims to dig up a small, yet always evasive, fortune.

Carey, a Berkeley student in the 1960’s, uses his rural vantage to criticize the larger society beyond the Ozarks’ gates; those criticisms, however, lack the rancor and illiberality of his youthful bent. Sometimes his observations are quite striking. “Seven years without radio, television, or newspapers made it clear to me that until then I had been living in a world defined by values other than my own, a world of description, handed down to me by family, culture, and the language through which I was taught to filter my impressions.” (There: in 50-odd words Carey distills the whole point of Bill McKibben’s recent book The Age of Missing Information, a sometimes long-winded excursus in media criticism.) Other of Carey’s remarks can be a little dippy: “I have many suits, this human dress but one.” Fortunately, those lapses are rare.

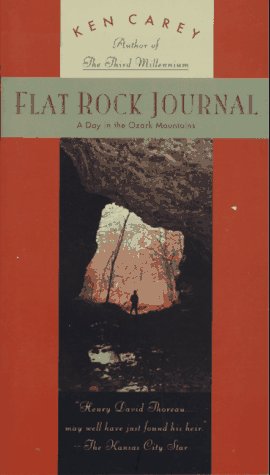

To judge by his book. Ken Carey has found a true home for himself and his family in this neglected corner of America. In the Ozarks, he notes with satisfaction, poverty becomes a kind of wealth. If the land were easier of access, it would have been stripped bare, like much of the comparatively gentle Appalachians to the east. Poor though they may be, the Missouri highlands have been good to Ken Carey, giving him the footing for an always engaging memoir, full of reverence for nature and the good life in the spirit of Henry David Thoreau—and of William Shakespeare, whose ideal human, like Carey, “Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks. Sermons in stone, and good in everything.”

[Flat Rock Journal, by Ken Carey (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco) 230 pp., $18.00]

Leave a Reply