A New World Begins: The History of the French Revolution by Jeremy D. Popkin; Basic Books; 640 pp., $35.00

Zhou Enlai was asked in the early 1970s what he, one of the architects of the Chinese communist revolution, thought of the French Revolution. His response: “Too early to say.”

The international press seized upon that comment, which satisfied every cliché about Eternal China and served as proof of Zhou’s profundity and long-range vision of history. Alas, we now know the anecdote is proof only of Zhou’s confusion and faulty hearing, as he thought he was responding to a question about the much more recent student uprisings in Paris. Perhaps it’s also proof of the journalistic habit of not allowing the facts to interfere with a good story.

Nevertheless, the story bears repeating. It reminds us that historical events can indeed have new meanings for the societies that they help create and for anyone seeking instruction, illumination, or diversion.

Jeremy Popkin, whose Short History of the French Revolution, now in its seventh edition, has been a staple of undergraduate syllabi for decades, confronts this question directly in his new book, which is a more comprehensive narrative aimed at a broad, educated audience. Considering A New World Begins, both a culmination of his scholarly career and a contribution to contemporary debates, Popkin attempts to show how much of modern politics was born in the French Revolution, and how knowing its history can enrich our understanding of today’s political challenges.

Popkin’s general approach is sober and seeks balance. As he puts it in his introduction, “the Revolution’s message and its outcome remain ambiguous.” Even if the ideas that it unleashed, such as nationalism, republicanism, and individual rights are “part of the heritage of democracy,” the subsequent violence and oppression in the name of those ideals cannot be ignored either.

“The respect for individual rights inherent in the Revolution’s own principles does require us to recognize the humanity of those who opposed it” Popkin admits, “and it requires us as well to consider the views of those who paid a price for objecting that the movement did not always fulfill its own promises.”

Reflecting the development of his own scholarship and broader trends in the literature, Popkin makes a special point to include both discussions of the role of women in the Revolution and also its relationship to the vexed question of slavery in France’s Caribbean colonies. The bulk of his story, however, takes place in l’Hexagone—as mainland metropolitan France is known—with only occasional forays into developments elsewhere on the Continent or overseas.

Popkin begins and ends his book with references to ironically paired biographies. The first links Louis XVI with glazier Jacques-Louis Ménétra. The two were near contemporaries, and Ménétra was one of the first Frenchmen of his station to publish a memoir, allowing for fascinating comparative glimpses into the early days of the Revolution.

The second is a pair of revolutionaries, Jean-Marie Goujon and Pierre François Tissot. Goujon, a passionate speaker and radical leader, died in 1795; Tissot, less fiery, gradually abandoned radical politics and became a businessman and academic. Tissot made his peace with Napoleon and the Bourbon restoration, writing one of the first histories of the Revolution and becoming one of the few Frenchmen who both participated in the events of 1789 and lived to see the proclamation of the Second Republic in 1848.

Those human stories provide dramatic punch and are useful reminders of the short span during which France, Europe, and the world were turned upside down.

In the body of the book, Popkin’s narrative decisions are conventional. He begins with a broad discussion of the life of Louis XVI and the society that produced him. He then covers the economic and political crises that led to the dramas of the Estates General, France’s pre-revolutionary legislative body, including the first revolutionary act in the Tennis Court Oath, leading to the storming of the Bastille, and the Terror.

The book’s first third takes the story up to the royal family’s failed attempt to escape the Revolution in June 1791. From that point on, Popkin’s focus is on the effort to create a French republic. The narrative highlights the personalities that shaped the revolution, from Marquis de Lafayette’s doomed efforts to preserve the constitutional monarchy, to the republican efforts of Jacques Pierre Brissot and the moderate Girondins, to the excesses of radical Jacobins such as Georges Danton, Jean-Paul Marat, and Maximilien de Robespierre.

For readers unfamiliar with the less dramatic aspects of the history, Popkin devotes three long chapters to the years after the Thermidorian Reaction, during which the Republic ended the Terror and overthrew Robespierre. During this period, from the summer of 1794 to the fall of 1799, different factions struggled to build a new republic under the multi-headed executive of the French Directory, the five-member ruling committee of the Revolution. This period is often disregarded by those who want to rush from Robespierre to Napoleon’s coup. In Popkin’s hands, however, the ebb and flow of parliamentary arguments, draft constitutions, and uprisings radical and royalist provide a series of important examples of how difficult, if not impossible, it is for radical change to give way to stability.

Befitting a narrative that focuses on the fate of the republic, Popkin ends his narrative with Napoleon’s coronation in 1804, leaving the empire as a story for itself. Though even there, Popkin notes wryly that when the Emperor returned from Elba in 1815, he tried to justify his renewed rule by calling on the people to rise up as they had in 1792, and even inveigled the liberal journalist Benjamin Constant to draft an addition to the imperial constitution promising the revolutionary freedoms his previous regime had undermined. “Even Napoleon realized that the ideals of the Revolution lived on,” Popkin notes—though it did not save him.

Readers familiar and unfamiliar with the history of the Revolution can read this brisk narrative with profit. Those who do make the effort should be alert to the many incidents and quotations that betray not only Popkin’s earnest small-r republicanism but also his eye for historical irony. For the most important lesson drawn from any history of the Revolution is the power of unintended consequences, and the dangers that arise when those who unleash forces prove unable to control them.

This insight was certainly best expressed by those who built the First Republic, such as the Girondist Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud. Dragged to the guillotine by his Jacobin enemies in 1793, he left us with the bon mot: “The revolution, like Saturn, devours its children.” More self-consciously dramatic, another republican stalwart, Madame Roland, made sure that a friend was standing close to the guillotine to hear her last words: “Oh, Liberty, what crimes are committed in your name!”

This insight was certainly best expressed by those who built the First Republic, such as the Girondist Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud. Dragged to the guillotine by his Jacobin enemies in 1793, he left us with the bon mot: “The revolution, like Saturn, devours its children.” More self-consciously dramatic, another republican stalwart, Madame Roland, made sure that a friend was standing close to the guillotine to hear her last words: “Oh, Liberty, what crimes are committed in your name!”

Conservatives with a well-developed sense for the tragic often nod sagely at such scenes, which highlight the fecklessness or evil of those who overthrew a king only to produce a tyrant emperor from the resulting chaos—one who turned Europe into a charnel house.

Yet there are lessons in this history for conservatives as well. As Popkin lays out quite convincingly, the overwhelming majority of aristocrats and clergy, even when presented with clear material evidence that the king needed concessions on taxes to avoid fiscal and political calamity, refused to sacrifice. Some denied there was a crisis at all; others thought they could simply ride it out, or perhaps turn it to their advantage against a weakened monarch.

Even the decision to call the Estates General was less a radical plot than a delaying tactic from aristocrats who refused concrete reforms. They stymied the king, thinking he would bend to their will, only to find within a few short years their privileges destroyed, their châteaux in flames, and the king in prison. Soon they found themselves mounting creaking wooden steps to visit Madame La Guillotine, accompanied by the rattle of tumbrels and jeers from the angry crowds in the Place de la Révolution. How many of them, if given the chance, would have gladly sent warnings to their earlier selves that it might have been wise to surrender a few extra livre to help balance the budget?

As Popkin quotes Alexis de Tocqueville, “the most perilous moment for a bad government is when it seeks to mend its ways.” Popkin’s narrative offers lessons in today’s perilous moment for those on both the right and the left—terms which are themselves part of the inheritance of the French Revolution. Today, increasingly rowdy crowds demand immediate radical change with no thought for where the journey might end, while conservatives warn that any concession would lead inevitably onto some slippery slope. As both sides seem prepared for battle à outrance (to the death), all may profit from studying the familiar yet underappreciated history of France and its Revolution. What will they learn? It’s too early to say.

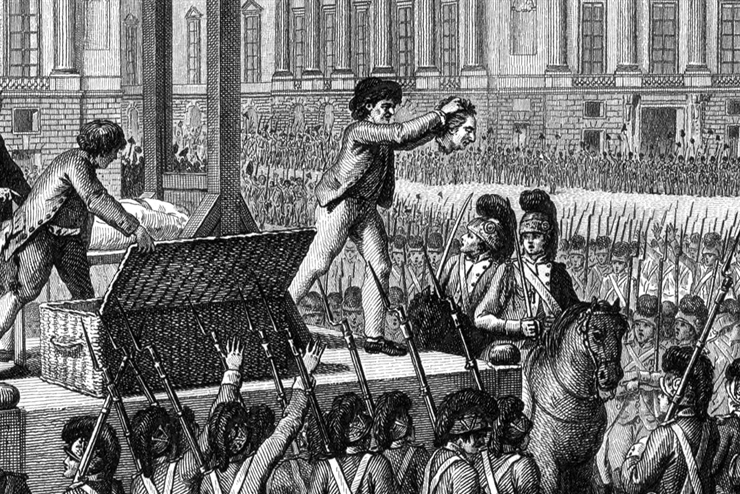

Image Credit:

above: detail from Execution of Louis XVI by Charles Monnet, 1794, engraving on paper (public domain)

Leave a Reply