He was unknown and disregarded during the whole of his short life and for years thereafter. But fortune relented. Gerard Manley Hopkins, dead for 30 years, was provided with an editor who had known, admired, and loved him and who had preserved the body of his work until he felt the time was ripe. Once known, his difficult poems found their own way. Good critics considered him the greatest of the great Victorian poets. Now his belated good fortune continues: he has found the biographer for whom any poet might wish: informed, sympathetic, perceptive, judicious. And all readers of Hopkins must hereafter feel themselves in debt to Robert Bernard Martin, professor emeritus of English at both Princeton University and the University of Hawaii.

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ life was short, obscure, and dogged by failure in his chosen vocation. His superiors in the Society of Jesus did their best to find a post where his manifest talents of mind and character might serve their order and bring Hopkins himself satisfaction and peace of mind. They failed. He suffered throughout his life from depressions so deep as to threaten his mental balance and, indeed, seems to have been happy at the end to accept death. The craft to which he applied himself with so many misgivings but with such devotion amid the manifold and trying exigencies of his life brought him neither understanding nor appreciation nor reputation. Only a handful of close friends even knew he wrote poetry. He habitually referred to himself, in letters and in verse, as “Time’s eunuch,” and his sense of sterility seemed the final cruel judgment on his life, his hopes, and his unvalued works.

Behold now how true is the ancient myth of the phoenix! A century ago Hopkins died of typhoid contracted in a filth-ridden Dublin. He was laid to rest among his fellow Jesuits in the Glasnevin cemetery, and a Latin inscription, one among some two hundred carved on a granite crucifix, is his only memorial. Yet from this earth, this grave, this dust, the poetry he wrote so painfully during his short, unhappy life has risen to speak like a trumpet to the modern ear, or like the golden echo of his own title. As the most powerful poet in an era of great poets, Hopkins left the record of his love, his suffering, and his faith in verse which, like the world of “God’s Grandeur,” is charged with energy and sustained by his passionate affirmation of the glory of creation.

Robert Bernard Martin’s biography gives a fully detailed picture of the circumstances and the social and intellectual background of Hopkins’ life: of his family, particularly his mother and father, with whom the poet had all his life a close, complex, and somewhat difficult relationship; of his education at school and at Balliol College, Oxford; of his conversion to Roman Catholicism at the age of 22, in the teeth of family, society, and friends and under the influence of the great John Henry Newman; of his even more extreme decision to join the Society of Jesus, in which eventually, after a long period of study and probation, he was ordained and in which he served all his life; and of those various posts where this dedicated priest preached and taught. In the course of his account. Professor Martin paints vivid pictures of Hopkins’ relationships with his many friends: friends as diverse as Walter Pater and Benjamin Jowett, Coventry Patmore, Robert Bridges—perhaps his closest friend, himself later Poet Laureate, to whom all readers of Hopkins owe their knowledge of his poetry—Canon Dixon, and the young Digby Dolben, dead at 19, whom Hopkins loved so deeply and whose early death was a lifelong grief to him. Professor Martin is clear and specific about Hopkins’ homoeroticism, which shaped his life and colored his verse and—far more valuable for an appreciation of that verse—shows how the poet’s repressed but powerful sexuality influenced and controlled the vocabulary, the imagery, and the pulsing emotion of his poems.

There are not many biographies that so illuminate the achievement as well as the life and character of their subjects. In Professor Martin’s book we see working harmoniously together the biographer, the stylist, the literary critic. For of what use is the most diligent and dedicated research, of what good is the keenest penetration into psyche or poem, unless these fruits can be presented in a persuasive and delectable manner? Hopkins has finally found a biographer who, like his editor and friend Bridges, sets him and his achievement forth, suffering and triumphant, to be known as fully as possible to all his admirers.

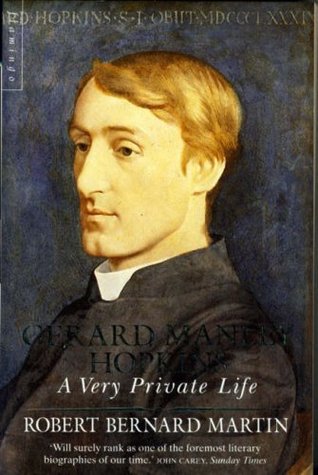

[Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Very Private Life, by Robert Bernard Martin (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons) 448 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply