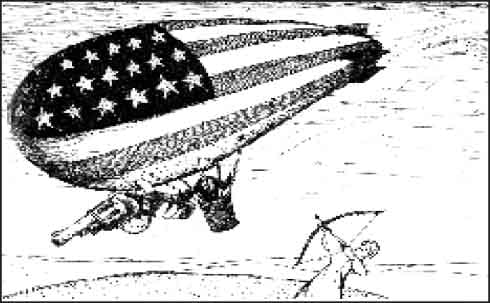

America’s present position is paradoxical. On the one hand, her unparalleled power and wealth are reflected in the astoundingly imperialist “National Security Strategy” unveiled last October, which asserts a right to stop any country “from pursuing a military build-up in hopes of surpassing or equaling the power of the United States.” That America is a global empire may be celebrated, regretted, or viewed with alarm, but it cannot be denied.

On the other hand, America is in deep moral decay. Her decadent elites are unwilling to confront a demographic deluge that can only end in population replacement. Her survival as a nation with distinct origins, traditions, and institutions is no longer uncertain but unlikely.

The paradox was aptly illustrated by the panic that gripped Washington, D.C., following the recent sniper attacks. The city trembled—the same proud city in which decisions are made that determine the destinies of millions of Iraqis, North Koreans, and Serbs. And September 11, far from proving the strength of the imperial edifice, displayed its underlying fragility. Another major terrorist outrage—and those in the know say that it is not a question of “if” but of “when”—would likely cause mass panic and an economic nosedive.

Americans simply lack the moral fiber necessary to maintain an empire. They would be well advised to consider the lessons of two previous attempts at imperial expansion at the tail ends of decaying civilizations.

Justinian heroically attempted to put the Roman Empire back together, but the recovery was short-lived. It drained the empire’s resources so thoroughly that, only decades after his death, Muslim hordes swept almost unopposed through the Holy Land, Egypt, and the rest of North Africa, conquered the Fertile Crescent, and twice besieged the imperial capital itself. While the fruits of the recovery lingered on for centuries in the splendor of Ravenna and Venice, we know, in hindsight, that the Eastern empire’s manpower and treasure would have been better deployed in protecting its borders and in consolidating its body politic.

Justinian’s inability to foresee the nature of long-term threats to his empire may justify his actions. The blunder committed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the last quarter of the 19th century, when it embarked on a policy of imperial expansion in the Balkans, was less pardonable: Many contemporaries understood the danger and warned that the experiment would prove fatal to the Habsburgs.

Austrian expansion, marked by the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina agreed upon at the Congress of Berlin (1878) and by the province’s subsequent annexation (1908), sought to address the problem of nationalist discontent by bringing external sources of agitation into Vienna’s orbit. This policy only aggravated the problem: In an age of patriotic awakening among its many small nations, the old and feeble supranational empire lacked the will and the resources to absorb Bosnia and to keep Serbia in check.

Expansion also led the Dual Monarchy to seek control of the corridor between Bosnia and the remainder of European Turkey, the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, which further complicated the “Eastern Question.” Its attempts to subjugate Serbia by means of a tariff war (1906-1911) proved ineffective and, indeed, enhanced Belgrade’s links to Paris and St. Petersburg. Meanwhile, the Habsburg Empire was growing increasingly frantic about the problem of Serbian nationalism, while simultaneously fanning its flames: For Franz Ferdinand to visit Sarajevo on St. Vitus Day in 1914 was an act of folly comparable to the Prince of Wales parading through Dublin on St. Patrick’s Day. There is a sense in which World War I was caused by Vienna’s Serbophobia, and some segments of the German-speaking world have blamed the Serbs ever since for the first of their two great disasters in the 20th century.

World War I destroyed the Habsburgs and the rest of Europe with them, but the gross carnage was possible only because millions of young men whose countries were not attacked were willing to die for the imperial ideal. Britain’s lads volunteered for king and country, even though the kaiser had no intention of mounting an invasion across the Straits of Dover, and the mother country could count on the loyalty of millions of Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, and South Africans whose graves dot the landscape of Picardy. Italy’s war aims included expansion to the eastern shore of the Adriatic, the land “where only the stones are Italian,” in the name of Venice’s long-dead glory. This ambition was to cost Italy half a million lives and lead her into another disaster a generation later. The extent of Germany’s appetites became obvious at Brest-Litovsk, and the same lust for the Slavic-inhabited Lebensraum led her into the terminal blunder known as “Barbarossa” a quarter of a century later.

The cost of empire is the inevitable ruin of the nation that embraces the project. Such a warning will not impress the ideologues of “benevolent global hegemony,” but I am comforted by the thought that America’s decline may commence sooner than we think, and that it will not last as long as the decline of Rome, Byzantium, or the Ottoman caliphate. The grounds for such cautious optimism are to be found in certain features of our postmodern empire that make it different from previous imperial endeavors.

First of all, the American Empire is feminized. All rising and strong empires have celebrated manly virtues. It was sweet and decorous to march east with Alexander, to vanquish Gaul with Caesar, to ride with the Old Guard at Austerlitz, and to administer India with Clive. On the other hand, as we have seen with the Hellenistic heirs to Greece and late Rome, when virility is gone, sensuality, magic, mystical religion, and astrology set in. The American Empire’s doctrine of “humanitarian intervention,” the urge to mediate its dominance in terms of “saving children” or bringing “human rights” to the “oppressed” is a form of effeminate mystical religion.

Our empire keeps trumpeting itself. It is morbidly self-conscious rather than heroically spontaneous. A strong, viable empire does not need to justify itself to its citizens or its subjects: The former have a natural understanding of the project and readily identify with it; the latter simply do not matter—they obey. In the United States, by contrast, we are bombarded by self-justifying theories based on ideological assumptions that are alien to America. True empire-builders have no need of “ideology”—“a system of interested deceit”—because they have a vibrant culture. The proponents of postmodern empire constantly complain that the citizenry needs to be “engaged,” “educated,” and “informed,” because their notions remain uninternalized by most Americans. For that reason, the emerging empire is unable to count on the self-sacrificial enthusiasm of its rank-and-file.

In the heyday of the Raj, a district commissioner would dress for dinner even though he ate alone, the temperature was over a hundred degrees, and he was the only European within a hundred miles. Today’s Americans are more akin to Epicurus, a product of Hellenistic decadence, who preached maximizing pleasure and minimizing suffering: “The end of all our actions is to be free from pain and fear, and, once we have attained all this . . . the living creature has no need to go in search of something that is lacking.” The Zeitgeist is reflected in the obstinate refusal of young Americans to enlist even in the jingoistic aftermath of September 11 and in the attempt of the recruiters to induce them by an array of strictly material incentives.

Continuation of the imperial experiment will further strain America’s weakened moral fiber and erode her liberties. We need a prudent reallocation of resources combined with a realistic assessment of our current moral capabilities and a pragmatic evaluation of the real threats to our civilization: Third World immigration and Islam. That is the path of physical survival, cultural revival, and spiritual renewal. It may not seem likely, but miracles do happen.

Leave a Reply