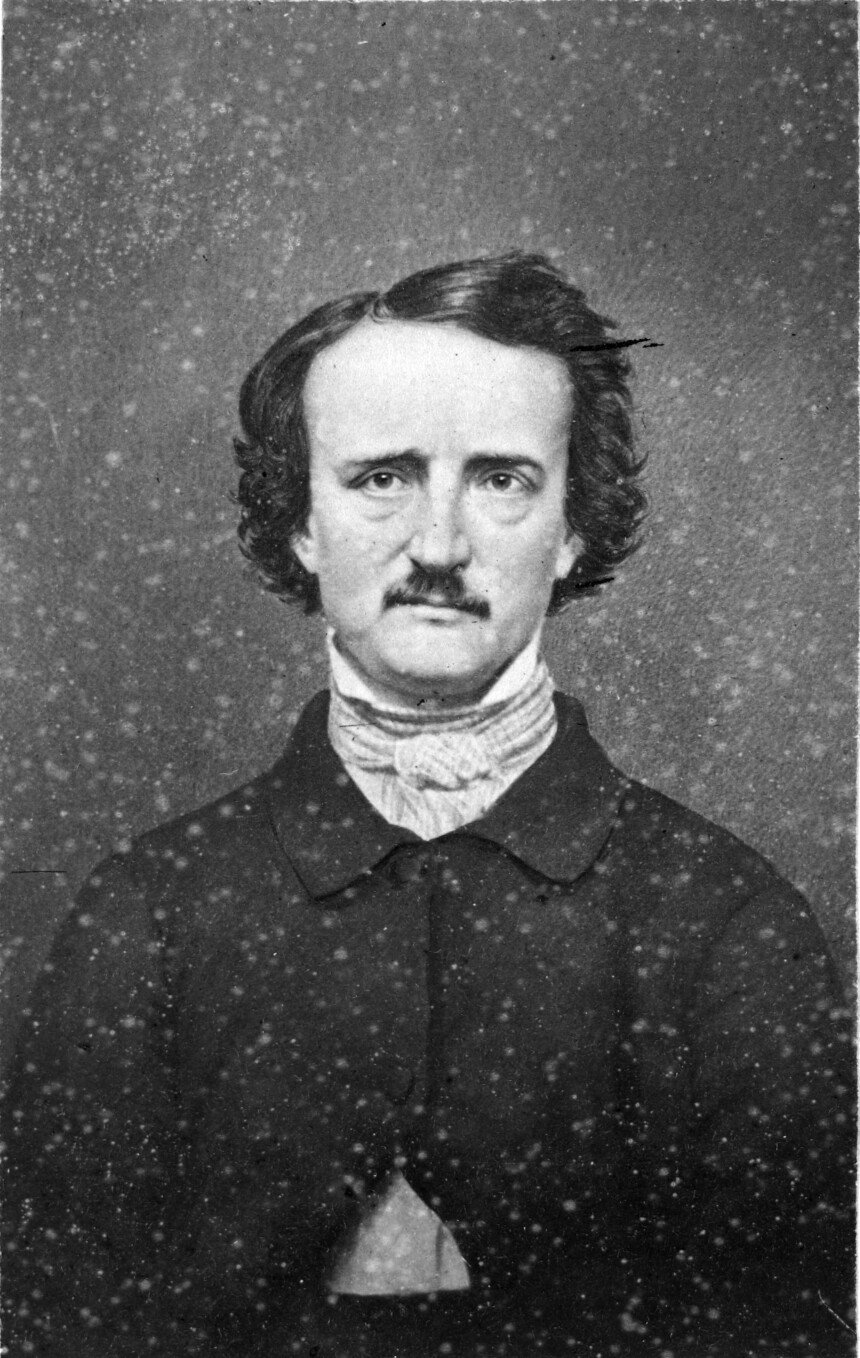

If there are two vocations more opposite than, on the one hand, the starving but gifted poet, mystery and horror-story writer, and prolific essayist and, on the other, the obscenely rich, ambulance-chasing attorney, this writer does not know them. Yet these two are conjoined at birth. To understand this, one must know something about the life of the famed author of “The Raven,” “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” and brilliant essays on many cultural and political topics.

Every fact of Edgar Allan Poe’s life is hotly disputed, as there is a wide range of sources, primary and secondary, to sift through, as well as thousands of utterly contradictory letters from dozens of Poe’s contemporaries. But more important is his character as it is known to have developed.

Edgar Poe was born to a family of stage actors who lived in Richmond, Virginia. When the boy was an infant his father mysteriously disappeared while the family was on tour in New York, and his mother died of “consumption” when Poe was three, in 1811. Elizabeth Poe had been famed as the most beautiful leading lady in the South, and had performed to excellent reviews in Europe.

Acting went hand in hand with extreme poverty. Three-year-old Edgar was left a penniless orphan with nothing but an obsessive love for his young, beautiful, famous, and doomed mother.

The citizen who chose to take him in was rich John Allan of Richmond, a Scotsman, and only the second multimillionaire in the entire South. Allan was a grasping merchant and deeply resented his lack of social standing despite his wealth. He therefore decided to dabble in philanthropy, and the grudging adoption of widely pitied little Edgar suited Mr. Allan’s venture. Mr. Allan did, however, insist that his own surname be inserted as Edgar’s middle name.

Allan remained, first, last, and always, a merchant out to increase his fortune. Accordingly, Edgar Allan Poe was put to menial work in Allan’s firm. Poe was intermittently “educated,” and began his private writings at the age of 14.

Whether conscience or social disapproval prompted the move, Allan eventually sent his teenage ward to the University of Virginia. Despite an excellent academic record there, Poe soon found himself falling into gambling, buying expensive clothing, and showing off in the social life of the university town. He “borrowed” money from Allan and from every acquaintance he could make, to retain the image of a rich young Southern gentleman, either sending the bills to Allan or simply not paying them.

Poe knew he would inherit from John Allan someday.

Edgar’s profligacy could not last long, and Mr. Allan removed him from the school and threw the boy out into the world. He was permanently cured of the spendthrift lifestyle. After a period of near starvation, Poe lied about his age and, under the pseudonym E.A. Perry, enlisted in the Army, where he served honorably, rising to the highest enlisted grade of regimental sergeant-major with lightning speed (two years). While stationed in Charleston he wrote and published his first mystery story, “The Gold-Bug,” set in that harbor. Upon learning of this, John Allan, respecting only “officers and gentlemen,” procured Poe’s appointment to the U.S. military academy at West Point. Allan insisted on this partly because it was free and partly because West Point was far away.

But West Point was not totally free: Each cadet was required to supply his own firewood for the northern winters, and Allan refused to send any, or the money to procure it. Poe almost froze to death, despite some donations from his cadet friends, including several future Confederate generals. By now Poe’s skill at begging was being well honed, but Allan remained unaffected. The myth that Poe’s expulsion was caused by a sensitive young poet’s unsuitability to “rough, crude” military life is exploded by several facts: He was well liked and respected by the other cadets, he had a strong record at the academy, and he had demonstrated his fitness for the military by his previous exceptional service. Poe engineered his own expulsion; a cadet was not free to resign without his father’s permission, and Allan would not give his. One morning the “uniform of the day” was “white cross-belts,” and Poe lined up for inspection wearing only the belts. After expulsion he dedicated his first (self-published) book to the Corps of Cadets. (The only remaining copy is in the West Point library.)

Poe returned to Richmond and, through various schemes, took over and expanded the Southern Literary Messenger, a hitherto unknown monthly, which soon, under Poe’s hand, became the center of culture for the entire South. The South of the time admired literary avocations for true gentlemen. Poe didn’t try to break into the Northern market because he came to loathe that region. He claimed many causes in the Messenger, among them the coldness of the climate; the “lack of breeding” of Northern ladies; the inferiority, in his opinion, of Yankee poets and essayists—Longfellow, Whittier, Holmes, Emerson, etc.—and the Transcendentalist religion and other forms of spiritualism that swept the formerly Puritan intellectual classes in the Northeast, which Poe considered both heretical and silly. The only Northern writer Poe ever admired was Nathaniel Hawthorne. However, he could not find enough talented contributors in the South, either—at least on short notice—so he was forced to write almost all the poems, stories, and essays in his Richmond magazine under various pseudonyms, while paying the overhead for an intellectual publication out of his own pocket. But he patiently awaited his “great expectations” from John Allan’s death.

When the magazine folded, Poe moved to Baltimore, which, at the time, was a deeply Southern city, and considered by Poe his second home. There a widowed aunt had admired his writing to such a degree that she charged him no rent, preferring the title “landlady” over the blood connection. Poe and his landlady’s 13-year-old daughter fell in love and married (which was legal in the South), to her mother’s great joy. Later, when they had to move to the North, the couple remarried several times so as not to shock the sensibilities of those people as to the youth of his bride. Poe never, of course, mentioned that she was his first cousin.

All this time, Poe awaited old Allan’s death, and then the probate of his vast inheritance. Certainly, Poe had been “disinherited,” by Allan’s word, many times, but there had always been a grudging reconciliation. For a while, his major means of support were contributions to the Northern magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book.

The greatest novelist of the Old South, William Gilmore Simms, wrote an extremely long letter to Poe, apparently in reply to the latter’s ostensible request for advice on Americans’ troubles with English pirating of their works; Poe’s own were reprinted throughout England and translated and published in France, without royalties. Poe also begged Simms for money. Simms began with a long exposition of his admiration of Poe’s genius and Simms’ familiarity with all his work. He explained that he had no money to give. He admitted that he knew of Poe’s tainted reputation as a man, but did not believe it. Then he offered Poe some good advice. Poe had taken to picking fights with Godey’s, which had paid him well, and Simms reminded Poe that Simms, personally, had persuaded Godey’s to publish and pay Poe. He must stop quarreling with the Yankees, and must attempt to reenter his proper social class, by a little humility, to the point of obscurity for a while. Then Simms gave his best advice: He recommended prudence, a virtue that was disparaged by the literary world, but which was Poe’s only hope unless he wanted total destruction. Simms signed his letter “sorrowfully, yr obdt. Servt.”

Poe didn’t listen.

Something must be said about Poe’s vices. He was, by now, an inveterate beggar—any letter, or word, of praise for his work received a letter in response begging for money. This led to lying about himself, which has frustrated Poe’s biographers ever since. Although Poe’s family was in England briefly as actors, with the infant Poe, and Allan took him to Britain for a short visit, Poe claimed to have been educated in England, and aped English mannerisms. He claimed that his name derived from the Italian river Po, to account for his artistic sense. Of course, when he finally moved to the North, he was suddenly blessed with plenty of “Southern plantations.” Most obvious to any Poe scholar was that he set many of his short stories and detective mysteries in Europe, to live the picturesque and romantic life he had made up for himself.

Indeed, Poe wrote that he considered the Southern part of the United States to be an improved extension of Europe’s past glories, architecture, chivalry, mystery, and lifestyle (though he condemned Europe’s corrupt politics), and therefore saw nothing incongruous in combining the best of both regions in his writings, or alternating between them. Certainly, Southerners had adored Waverley, Ivanhoe, and others of Sir Walter Scott’s European historical novels. (One Northern historian of the last century has gone so far as to claim that Scott’s novels were the cause of the War Between the States.) By contrast, Poe thought of the Northern United States as consisting of “dark little gremlins secretly running the ‘Machine’” through conspiracy.

Poe’s love for his own region is made clear by his essays on poetry and short-story writing as well as on many other subjects. Many times he stressed his opinion of beauty: It isn’t just prettiness, but must always be mingled with a flaw—whether it be a scar on a woman or a ruined turret on an otherwise stunning architectural work. (And what is the greatest “flaw” in this world but death?) The flaw that mars and therefore completes loveliness creates tragedy—a characteristic Poe applied not only to his own life, but to everything he laid his eyes on or admired. His own flaws were clearly contributors to his tragedies. Whether this turn of Poe’s mind was the major cause of his love for the South would take a philosopher or a psychiatrist to decide. Could he see enough into the future to grieve the Lost Cause? Were the signs of the impending doom already visible to the perspicacious? Thomas Jefferson clearly saw it enough to “Southernize” his political views late in life on the issues of agrarianism, slavery, and other Southern institutions. General Lee “went South” with more sorrow for Virginia than for the Union. Writers from John C. Calhoun to William Gilmore Simms must have seen this tragedy approaching. Could this linkage of beauty and tragedy have had less influence on one of Edgar Allan Poe’s sensitivity?

Since Poe’s most popular works today are the stories, readers think of his settings being in Europe, as many of the stories are, but most of his other work is as American as any other written here at the time. A few out of dozens of Poe’s poems that could be considered “romantic European” in style might include “Eldorado,” “The Haunted Palace” (which many critics have read as his own unfounded fear of approaching insanity), “Ulalume,” and a handful explicitly set in Europe. Poe’s great essays, of course, all concern the South and the America of his day, when they reference any specific location at all.

Contrary to myth, Poe did not drink often. He had a disease worse than common alcoholism: As seldom as he touched liquor, one drink and he fell to the floor unconscious and on the verge of death. This led to his horror of premature burial. Similarly, Poe took no drugs. But he had studied De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater and described the effects of drugs too accurately, leading to the mistaken belief that Poe was a dope addict. His last vice, though most would not consider it one, was gullibility. In order to use Poe’s services, his worst Northern enemy, the fashionable hack Rufus Griswold, endeared himself to Poe so much that Poe made Griswold his literary executor with exclusive rights to Poe’s biography. The hateful book was a bestseller after Poe’s death and completely destroyed his reputation. His old landlady, aunt, and mother-in-law spent the rest of her life trying to resurrect Poe’s reputation.

Poe moved to the North because that was where the money was for literary figures. The wealthy Longfellow, Lowell, Emerson, and their coterie of poets and essayists received most of their money from theater lectures and recitations in Boston, and Poe’s literary fame had reached that far (though the “insult” that Poe was a “professional Southerner” had not, yet). He was eventually hired by the Knickerbocker Review and lived in a farm cabin with his wife and mother-in-law in what is now The Bronx. It was there that he wrote “The Raven” and may of his other famous poems, essays, and stories. It was also there that his beloved, still-child bride died, apparently of malnutrition.

For a while, Poe rose as a literary celebrity. Unfortunately, he was forced to read everything written by the New England poets. He despised them, and broadcast it in his first Northern essays. Then Poe wrote long essays on each poet in particular, beginning with Longfellow, whom he proved without a doubt to be a pathological plagiarist, poem by poem. (Poe looked up the original poems, usually antique Scottish.) Poe was, of course, subsequently fired from the Knickerbocker Review (edited by this writer’s one Northern ancestor, to our family’s shame) and insulted, in print and everywhere he went. He received no invitations from Boston for theatrical recitations. This time marks the first use of “professional Southerner” that this writer has found, even though Poe had tried to hide his origins by attributing his first book to “A Bostonian.” This might also have been why Poe set so many stories in Europe.

It didn’t help that some of his essays defended John C. Calhoun and states’ rights, and opposed the immediate and national abolition of slavery. Nor did it help that Poe’s essays on “ratiocination” (disciplined reason), though meant to explain his mystery stories and essays, undermined Transcendentalism. Nor did it help that he insisted in his essays that all poems have clear rhyme and meter—that they were songs without music, and therefore should be read rather “sing-song,” as most readers of the time had little access to music at home. (Even today our young are wrongly taught to “read poetry as they would prose.” The modern teaching of reading poetry has so uglified the art form that it is dying out among the young, who would otherwise have a gift for true beauty. Try reading Poe’s “The Bells” or “Annabel Lee” in the modern prosaic manner. Poe designed them to be impossible to read that way.)

Poe’s essays, as his admirers know, are the vast majority of his corpus, though they are forgotten for political reasons. They vary in range of subject matter from furniture, to architecture, to criminal detection, to journalism, to mechanical hoaxes, to religion, as well as to politics and poetry and the art of plagiarism.

Poe found himself unpopular, fired sequentially, and forced to leave the North, contracts or no contracts. Once again, he could have used a good lawyer, but the mirage of a large inheritance still gave him hope, especially now that Allan was dead and the probate of his will had been under way for some time.

Poe died of exposure in 1849, at the age of 41, in a Baltimore charity hospital, ignorant of the legal circus in Richmond that was still and unnecessarily dragging on.

At about this same time, Charles Dickens published his own famous novel, Bleak House, which concerned a promising, aristocratic, but indolent young man who obsessively awaited the probate of his elder’s estate, only to find, at the end of many years of litigation, the barristers celebrating that the case was over: The money had all gone to legal fees, and there was none left to dispute by the heirs, including the now penniless and consumptive protagonist.

Poe did the same thing at roughly the same time, without the indolence. Another coincidence was that Dickens was later a great enthusiast for the South and the Confederacy, as Poe, the “professional Southerner,” was and would have been.

Wealthy old man Allan had handwritten his will without witnesses, leaving his huge estate to “my children.” But he had failed to mention in his will that he had several categories of “children”: Those of his marriage; those “of his body” through numerous paramours; those whom he had taken under his wing for free labor and introduced as his children, but never legalized; and, of course, those he had legally adopted, of whom Edgar Allan Poe was famously a member. Worse, each category had plenty of presumptive heirs within it, and none seemed inclined to join forces.

The civil law in Virginia at that time was unclear on which “children” would be the true heirs of the South’s great multimillionaire. Virginia law was still based on English common law. Naturally, each would-be heir, except Poe, hired his own attorney. When the litigants ran out of Richmond lawyers, they hired attorneys from as far away as New England and Georgia, and one English barrister. The word got around, and other lawyers came and bought their way into the litigation. There was time enough for some people to read the law and be admitted to the bar, just for this probate.

One legal expert lists the howlers in Allan’s will, which deepened the lawyers’ gold mine: Sections in this “holographic” will were clearly written by someone else, though in the first person; codicils without dates, or witnesses, or unsigned; four pages of irrelevant thoughts that wandered through Allan’s mind; ambiguities, incongruous and even conflicting provisions, such as treating twins as if they were one person; specific bequests, later followed by “my whole estate”; “eldest child” and “youngest child” reversed; no executors or trustees, although the money was to be held until an unspecified child reached a certain age; “at the expiration of five years” refers to nothing in particular; “share of boys to be double that of girls,” which knocks the rest of the will in a cocked hat. The expert concluded, “This is less than an untechnical will; it is grossly stupid and ineffectual.”

Under current law, such a will would be summarily dismissed, and Allan’s entire estate would have quickly gone by Descent and Distribution, which would have been to Poe’s great benefit while he was alive. But not in those days. Nevertheless, the case could have been quickly settled out of court, but the army of lawyers had no desire to kill their cash cow.

There is little doubt that any decent, rapid probate would have saved Poe’s life, and given us ten or thirty years of beautiful poetry and thrilling literature, when Poe would have been at his highest powers. The Confederacy might have been the world’s center of culture, winning allies worldwide for her soldiers while they fought for independence. Poverty does not usually benefit art—vide Lord Byron, Poe’s early model, or Shelley or Tennyson—especially if poverty kills the artist.

During the probate almost as many new legal firms were founded in Richmond as had existed in the whole of the South. The fame of Poe’s name and Allan’s wealth drew lawyers like flies. We don’t know if, when Allan’s money finally ran out, the attorneys celebrated as boisterously as they did in Dickens’ Bleak House. The final end of the probate did not harm the legal profession: Once established, attorneys create their own market.

“The Jolly Testator” (attributed to Lord Neaves), a favorite of lawyers on two continents, is a song of gratitude for injudicious probates. It ridicules men like Edgar Allan Poe’s adoptive father:

He writes and erases, he blunders and blots,

He produces such puzzles and Gordian knots,

That a lawyer, intending to frame the thing ill,

Couldn’t match the testator who makes his own will.

Leave a Reply