Bridge of Spies

Produced by DreamWorks SKG

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Screenplay by Matt Charman,

Ethan Coen, and Joel Coen

Distributed by Touchstone Pictures

Steven Spielberg’s new movie Bridge of Spies recounts the Cold War spy swap America made with the Soviet Union in 1962. We gave the Russkies atom spy Col. Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance), and they returned our downed U2 reconnaissance pilot Gary Powers. The film is beautiful to behold, filled with superior performances, and, if taken at face value, seriously misleading. It lists so far left, you half expect to hear bilge pumps on the soundtrack.

The film begins in 1957 with the arrest of Soviet spy Rudolf Abel, born William Fisher. Spielberg and his writers (Matt Charman, and Ethan and Joel Coen) contrive to make of Fisher a wholly admirable martyr-hero to the Soviet cause. They seem to forget that the KGB sent him here to do grave damage to America. Beyond acquiring and sending atomic plans to his home country, Fisher was serving far vaster aims. His spy masters had gone so far as to imagine that, should the Soviet Union prevail in a war on its Western enemy, he might one day have a hand in taking over the American East Coast. The key to winning this war would be, of course, the atomic information Fisher was sending them. This meant they were envisioning the deaths of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Americans. And why wouldn’t they? Hadn’t Stalin murdered 22 million of his own people before he shuffled off this mortal coil in 1952? Why shouldn’t Americans contribute their mite to the communist cause? This, then, is the man Spielberg and company think we should admire.

To be fair, Spielberg has followed the lead of Fisher’s court-appointed American defense attorney, James B. Donovan (Tom Hanks), who explains in his 1964 account of his involvement in the Fisher and Powers cases, Strangers on a Bridge, that he came to admire Fisher’s stoic resolve. Here, he marveled, was a man who was ready to face doom rather than cooperate with his American captors. There’s no question that Fisher was brave. But what about his cause? He was committed to an ideology that openly professed a morality in which ends justified means. He was wholly on board with Stalin’s breaking of those millions of eggs to make his rancid communist omelet. Donovan, a conventional liberal, apparently was unable to make the relevant distinctions. Yes, Fisher was stalwart, well educated, talented, and witty, but he also subscribed to a political philosophy that condoned murder when it served the expedience of the moment. Donovan never acknowledges this in his book, probably because, as a bien pensant liberal, he never entertained the notion that a man of refined bearing and tastes such as Fisher could countenance murder as an instrument of politics. On such naiveté civilizations founder.

Fisher was born and raised in England, where his revolutionary father had fled in 1903 in order to evade czarist persecution in the Mother Country. In the 1920’s his father brought him back to Russia, the better to enjoy the fruits of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The younger Fisher joined the army and, later, the KGB to serve the cause. He did so well as a radio technician practicing deception against the Nazis that the KGB sent him to America in 1948 to practice some more.

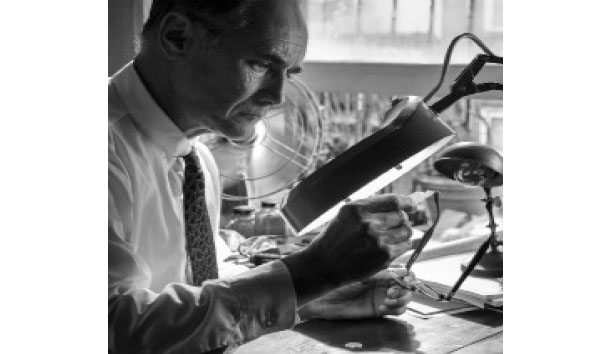

Having established his cover identity as a photographer, he began to gather information from Soviet agents stationed in New Mexico and elsewhere about America’s nuclear plans, which he dutifully transmitted to Moscow by means of his shortwave radio.

And what of those Americans sworn to stymie such foreign skullduggery? According to Spielberg, the FBI and the CIA were to a man either bumbling fools or vicious bully boys. In an early scene, we watch about 15 FBI agents sweatily galumph up the grimy stairs to Fisher’s Brooklyn studio apartment, only to discover he’s left ahead of them. They then pursue him on the streets, where he effortlessly gives them the slip. When they later manage to corner him in the Manhattan hotel room where he conducts his espionage, he’s able to outwit them once again. Under their very noses, he palms and destroys a coded message. He’s a veritable wonder at his dubious craft. But is this true? Not according to Donovan, who reports that only three agents went to arrest Fisher, and that they quickly foiled his attempt to destroy evidence. It seems Spielberg and his writers were so intent on portraying Fisher as a superior creature that they couldn’t resist depicting the men who were doing all they could to protect our country as buffoons.

In the subsequent trial, Donovan’s legal defense of Fisher was not successful, but he did persuade the judge not to sentence him to death. Donovan argued that Fisher wasn’t an American citizen; he had been sent to our shores in the service of his country and should be regarded as a soldier and given the rights of an enemy combatant. Donovan clinched his argument by pointing out that America surely had agents in the Soviet Union. It followed that one day Fisher might prove far more valuable alive than dead. He could be exchanged, should one of our spies be apprehended in Russia. Five years later Donovan’s artful courtroom suggestion became a reality with the capture of Powers.

The second half of the film takes up Donovan’s mission to East Germany, where he’s sent to negotiate the exchange. Along the way, Donovan learns of an American doctoral student, Frederick Pryor, who has been arrested for being on the wrong side of the just-erected Berlin Wall and threatened with execution. When Donovan announces his intention to include Pryor as part of the swap, a weasel-faced CIA agent tells him not to go all bleeding heart. The mission, this fellow insists, is to obtain Powers’ release; the kid’s not to be part of the deal. As one would expect, Donovan indignantly refuses to comply. He’s being played by Hanks, after all. This makes for an interesting plot turn, especially if you’re unaware, as I was, that the CIA man and his warning are fabrications.

The film’s many departures from fact in the cause of ideological purity and ersatz excitement—including a wholly imaginary scene in which shots are fired into Donovan’s living room by citizens irate that he’s defending a commie—are, shall we say, unfortunate. When it comes to the physical details of time and place, Spielberg has been scrupulous. For the scenes on the New York City subway that Donovan takes to his offices in lower Manhattan, for instance, Spielberg acquired a 1950’s rail car in which Hanks sits among everyday commuters rocking placidly along to their everyday jobs. Why go to these lengths in verisimilitude if elsewhere you’re going to invent things that never happened?

As for the acting, Hanks gives yet another of his now patented everyman performances that have defined his later career. Here he’s a quietly determined citizen doing his duty. We watch him in an early scene arguing his corporate client’s case with an opposing attorney representing injured truck drivers. Donovan insists the individual suits be combined into one legal action. When his adversary plausibly avers this would go against fundamental insurance theory, Donovan smiles amiably but digs in his heels. In the cause of reducing his client’s costs, he’s admirably adamantine. The iron fist in the velvet glove. This, as we will learn, is the trait that will serve him well in the 11th-hour negotiations he must enter into with East German and Soviet officials when they try to welsh on their agreement to release both Powers and Pryor. Behind his smile and twinkling eyes, Donovan is shown to be as unyielding as a ferret. He reminds me of my Uncle James, a lawyer serving the interests of the Brooklyn Union Gas company in the 1950’s. He was one of those Roman Catholic Irishmen who, given the educational opportunity denied their parents, were then showing their mettle. A son of a waterfront dock worker, he had served in the Navy in the Pacific and, like Donovan, rose to be a commander in the naval reserve. He was tough, shrewd, and implacable in the pursuit of his company’s goals. While Donovan was higher up on the class ladder than my uncle, he wasn’t that far removed from his humbler origins and was well aware of the class issues that had preceded him and his kind. There’s no doubt these origins played their part in shaping these men. They knew how to play the game in which they found themselves.

Playing the role of Fisher surely posed a more difficult challenge. But the British Rylance is more than up to it. Using a perpetually downcast visage and unsmiling demeanor, he comes across as an entirely alienated man. When the FBI breaks into his room, he looks entirely unsurprised. They might be a passel of unloved relatives descending on him unexpectedly. He’s willing to tolerate them, but only from a glum sense of duty. Rylance’s Fisher is a professional’s professional, disciplined and unreadable. The performance enables you to see why Donovan admired Fisher: He had fallen under the spell of a champion dissimulator. After all, lawyers need to obscure their intentions in court. Should they know the man they’re defending is guilty, they must nevertheless proceed as though he weren’t. What’s not so easy to see is why Spielberg and his writers should also have come under this lawyerly mystique. You would think they would use their art to pierce Fisher’s shell and uncover the deadly motivations within. But, no, they allow themselves to be as misled as Donovan. They have bought into the Irishman’s argument that Fisher was just a soldier on a mission and, further, that America’s panicked reaction to him was an example of Red Scare hysteria inspired by the likes of Sen. Joseph McCarthy. The film asks us to believe this in the face of the clear evidence to the contrary. Communism, judged on its intentions rather than its deeds, remains Hollywood’s holy cause. After all, communists meant well, didn’t they? Let’s play a thought game: Imagine Fisher had been an idealistic Nazi intent on establishing an offshoot of the Reich in America for our citizens’ own good. Would he be given the admiring treatment this film accords the communist Fisher? Does snow fall on Rodeo Drive?

Leave a Reply