Ours is an age of politicization. No matter the problem, real or imagined, proposed solutions are always couched in the language of politics. No subject can be discussed without constant reference to its political ramifications. Whatever position a political leader may adopt with respect to a current “issue,” it must be judged not by its relevance to governance, but by its impact on upcoming elections. Everything, in short, is viewed through the prism of politics. Politics has come to occupy the center of the lives of many, if not most, Americans; it is the search engine for meaning in a secular world.

In his famous commencement address delivered at Harvard University in 1978, the Russian dissident writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn attempted to awaken his listeners to their condition: “We have placed too much hope in politics and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life.”

Solzhenitsyn was born Dec. 11, 1918 in Kislovodsk, a spa city in the North Caucasus region of Russia. The Bolsheviks had seized power a year earlier, but a civil war of annihilation raged until 1921 before the “Reds” achieved final victory. As a result, Solzhenitsyn was to live under Communist rule for more than 50 years. His was a miraculously long and eventful life. He survived combat in World War II, cancer, and eight years in what he called the Gulag Archipelago, the universe of Soviet forced labor camps.

The 1962 publication of Solzhenitsyn’s novel about the gulags, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, turned Solzhenitsyn from an obscure former zek (labor camp prisoner) into an international celebrity. In the years following, he was praised in the West as a political critic of the Soviet regime and therefore a friend of liberal democracy, a writer following in the footsteps of 19th-century Westernizers such as Ivan Turgenev and Aleksandr Herzen. Although he was an enemy of Stalinism, the novel is not primarily about politics but about the soul’s search for God. “Be glad you’re in prison,” young Alyoshka the Baptist tells Ivan. “Here you have time to think about your soul.”

The 1962 publication of Solzhenitsyn’s novel about the gulags, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, turned Solzhenitsyn from an obscure former zek (labor camp prisoner) into an international celebrity. In the years following, he was praised in the West as a political critic of the Soviet regime and therefore a friend of liberal democracy, a writer following in the footsteps of 19th-century Westernizers such as Ivan Turgenev and Aleksandr Herzen. Although he was an enemy of Stalinism, the novel is not primarily about politics but about the soul’s search for God. “Be glad you’re in prison,” young Alyoshka the Baptist tells Ivan. “Here you have time to think about your soul.”

The diplomat and historian George Kennan once observed that Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany were aberrations that stood outside of traditional systems of politics. On Sept. 5, 1973, Solzhenitsyn forwarded a private letter to Soviet leaders in which he made it clear that he did not consider authoritarianism in itself to be intolerable, but rather “the ideological lies that are daily foisted upon us.” This was a way of saying that the Bolshevik Revolution did something far worse than establish a tyrannical regime. Like the Nazi regime which followed more than a decade later, it sought to destroy the souls of those whom it subjugated.

Solzhenitsyn agreed with the exiled legal and religious philosopher Ivan Ilyin’s characterization of the revolutionary upheaval: “The political and economic reasons leading to this catastrophe are unquestionable, but its essence is deeper than politics and economics; it is spiritual.” In a postscript to a 1975 samizdat essay entitled “As Breathing and Consciousness Return,” Solzhenitsyn again made it clear that his concerns were fundamentally religious and moral—the state structure was of secondary significance:

That this is so, Christ himself teaches us. ‘Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s’—not because every Caesar deserves it, but because Caesar’s concern is not with the most important thing in our lives.

Early in his monumental history of the labor camp system, The Gulag Archipelago (1973), Solzhenitsyn states, “Let the reader who expects this book to be a political exposé slam its covers shut right now.” In a section entitled “The Soul and Barbed Wire,” he writes of the ascent of his own soul that had begun with his renunciation of survival “at any price.” That renunciation freed him to examine his conscience, to reflect upon his own weaknesses rather than those of others: “Reconsider all your previous life. Remember everything you did that was bad and shameful.”

Early in his monumental history of the labor camp system, The Gulag Archipelago (1973), Solzhenitsyn states, “Let the reader who expects this book to be a political exposé slam its covers shut right now.” In a section entitled “The Soul and Barbed Wire,” he writes of the ascent of his own soul that had begun with his renunciation of survival “at any price.” That renunciation freed him to examine his conscience, to reflect upon his own weaknesses rather than those of others: “Reconsider all your previous life. Remember everything you did that was bad and shameful.”

Suddenly, Solzhenitsyn became aware that he had never forgiven anyone for anything, that he had judged others without mercy. As a result of this self-scrutiny he perceived a profound irony: “I nourished my soul there, and I say without hesitation: Bless you, prison, for having been in my life!”

Solzhenitsyn recognized that the problems confronting Russians, indeed all men, were fundamentally spiritual, not political, in nature. No political system, therefore, could provide a solution to them, and that included democracy, which Solzhenitsyn, citing Joseph Schumpeter, referred to as “a surrogate faith for intellectuals deprived of religion.”

History knew of few democracies, he wrote. People had lived for centuries without them and were not always worse off for it. Russia herself had long existed under authoritarian rule and her people died without feeling that their lives had been wasted. If such systems had functioned for centuries, Solzhenitsyn thought it was fair to conclude that they could offer people a tolerable life.

In his Harvard address, Solzhenitsyn informed his audience with regret that, having lived in the West for four years, he could not recommend it as a model for a post-Communist Russia. He did not cite theoretical opposition to democratic political systems as his reason, however. He reflected that, “Through deep suffering, people in our country have now achieved a spiritual development of such intensity that the Western system in its present state of spiritual exhaustion does not look attractive.”

A political system should not, Solzhenitsyn argued, be measured by its military power or the size of its economy, but by the sum of the spiritual progress of individuals under its authority. In America he witnessed little spiritual progress but much evidence of decadence, including crime, pornography, intolerably vulgar music, and the identification of happiness as the ultimate goal in life. America suffered from the “forfeited right of people not to know, not to have their divine souls stuffed with gossip, nonsense, vain talk,” he wrote. “A person who works and leads a meaningful life has no need for this excessive and burdening flow of information.” This problem has, of course, grown much more severe since the creation of the internet.

A political system should not, Solzhenitsyn argued, be measured by its military power or the size of its economy, but by the sum of the spiritual progress of individuals under its authority. In America he witnessed little spiritual progress but much evidence of decadence, including crime, pornography, intolerably vulgar music, and the identification of happiness as the ultimate goal in life. America suffered from the “forfeited right of people not to know, not to have their divine souls stuffed with gossip, nonsense, vain talk,” he wrote. “A person who works and leads a meaningful life has no need for this excessive and burdening flow of information.” This problem has, of course, grown much more severe since the creation of the internet.

It isn’t necessary to read Solzhenitsyn for very long before one becomes aware of his sympathy for authoritarian governments of a non-despotic and nonideological character. In the “Author’s Note” to The Red Wheel (1971), his novelized four-volume history of the Russian Revolution, he informs his readers that the fictional Olda Andozerskaya (modeled after Alya, his second wife) is, “among other things, a vehicle for the [favorable] views on monarchy of Professor Ivan Aleksandrovich Ilyin.” More importantly, there was no figure in The Red Wheel, or in Russian history, whom he admired more than Pyotr Stolypin, prime minister of Russia from 1906 to 1911 and an authoritarian but liberal reformer who sought to transform peasants living in communes into smallholders. In Solzhenitsyn’s view, his assassination removed the one man who might have spared Russia war and revolution.

Solzhenitsyn was not alone in his admiration for Stolypin; he was later joined by Vladimir Putin, who chose the martyred leader as a role model. Putin was the driving force behind the erection in Moscow of a monument in his honor. Although the Russian president operates within a democratic framework, his personal style is authoritarian. On succeeding the alcoholic and incompetent Boris Yeltsin, a darling of the West, Putin presided over rapid economic growth, reined in the power of the so-called “oligarchs,” worked to restore Russian culture, and defended the moral teachings of the Russian Orthodox Church. Putin visited Solzhenitsyn’s suburban Moscow home on two occasions and earned the writer’s praise. “Putin inherited a ransacked and bewildered country, with a poor and demoralized people,” Solzhenitsyn told Der Spiegel just a year before his death in 2008. “And he started to do what was possible—a slow and gradual restoration.”

Although generally critical of the Western world, Solzhenitsyn expressed respect for Spain’s caudillo, General Francisco Franco, who “with firm tactics” had managed to keep his country Christian “against all history’s laws of decline.” After making a visit to Spain in 1976, just a year after Franco’s death, Solzhenitsyn reported that Spaniards could travel abroad freely, read newspapers from around the world, and criticize public policy, as indeed they had done, with some limitations, since the pluralistic reforms of the 1950s. “If [Russians] had such conditions,” he said, “we would be thunderstruck, we would say this was unprecedented freedom.” Franco’s Spain was in his estimation superior to the secular West and to the one democratic “experiment” in Russian history.

Although generally critical of the Western world, Solzhenitsyn expressed respect for Spain’s caudillo, General Francisco Franco, who “with firm tactics” had managed to keep his country Christian “against all history’s laws of decline.” After making a visit to Spain in 1976, just a year after Franco’s death, Solzhenitsyn reported that Spaniards could travel abroad freely, read newspapers from around the world, and criticize public policy, as indeed they had done, with some limitations, since the pluralistic reforms of the 1950s. “If [Russians] had such conditions,” he said, “we would be thunderstruck, we would say this was unprecedented freedom.” Franco’s Spain was in his estimation superior to the secular West and to the one democratic “experiment” in Russian history.

As he was conducting research for the third novel in The Red Wheel cycle at the Hoover Institution and elsewhere, Solzhenitsyn, to his surprise, arrived at a highly critical view of Russia’s Provisional Government that had come to power in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917, which he had once viewed with favor. For most Western historians, that revolution was a glorious, if short-lived, event in Russia’s history—the fall of the autocracy and the establishment of a liberal-democratic government. Solzhenitsyn viewed it as an anarchic catastrophe that paved the way for the Bolshevik coup d’état. His unsparing account of the first days of revolutionary turmoil has a contemporary ring.

As he writes in the series’ third book, March 1917, on the first day of that doomed revolution, a “craze began of smashing shop windows and ravaging, even looting shops.” On the third day, “The crowd started throwing empty bottles at the police.” Later that month the mob chased down and attacked police officers without mercy, shouting:

‘Beat them, grind them to sausage…with whatever’s handy—sticks, rifle butts, bayonets, stones, boots to the ear, heads on the pavement, break their bones, stomp them, trample them…. We don’t want to live with police anymore. We want to live in total freedom!’

Later still, “Each inhabitant of the capital…was left to fend for himself. Released criminals and the urban rabble were doing as they pleased.” Functional democracy, Solzhenitsyn observed, demands a high level of political discipline. “But this is precisely what we lacked in 1917, and one fears that there is even less of it today.”

As a political realist, however, Solzhenitsyn recognized that democracy was likely to be Russia’s future. He had read Tocqueville who believed, with regret, that democracy was the West’s destiny. “The whole flow of modern history,” the Russian wrote, “will unquestionably predispose us to choose democracy.” Yet democracy had been elevated “from a particular state structure into a sort of universal principle of human existence, almost a cult.”

For Solzhenitsyn, democracy was far from being a universal principle. Like Tocqueville, he looked for ways to mitigate its likely excesses. “We choose [democracy] in full awareness of its faults and with the intention of seeking ways to overcome them.” He did develop a sympathy for democracy at the local level, what he called “the democracy of small areas,” in part because he remembered the zemstva, those promising organs of rural self-government established in 1864 during the age of the Great Reforms under Tsar Alexander II, which had been replaced by the Bolsheviks with Soviet collectives.

Solzhenitsyn also recalled with pleasure the time he witnessed an election in the Swiss canton of Appenzell. Officials there spoke of individual freedoms linked to self-limitation, which Solzhenitsyn regarded as essential to responsible political and personal conduct. Freedom, in his view, had less to do with an external lack of restraint than with internal self-control. Based upon his experience in the gulag, he knew that “we can firmly assert our inner freedom even in an environment that is externally unfree.”

Solzhenitsyn also recalled with pleasure the time he witnessed an election in the Swiss canton of Appenzell. Officials there spoke of individual freedoms linked to self-limitation, which Solzhenitsyn regarded as essential to responsible political and personal conduct. Freedom, in his view, had less to do with an external lack of restraint than with internal self-control. Based upon his experience in the gulag, he knew that “we can firmly assert our inner freedom even in an environment that is externally unfree.”

On the other hand, after his years in the West, Solzhenitsyn concluded that “the notion of freedom has been diverted to unbridled passion, in other words, in the direction of the forces of evil (so that nobody’s ‘freedom’ would be limited!).”

Appenzell’s direct elections also received Solzhenitsyn’s approval. The Swiss citizens of that canton knew those whom they voted for and did not need a Ph.D. in political science to arrive at reasoned judgments concerning local housing, hospitals, and schools. To vote responsibly for national leaders whom they could not know or for proposed bills about which they were not competent to judge was, however, a different matter.

Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky had once pronounced universal and equal suffrage “the most absurd invention of the nineteenth century,” but Solzhenitsyn said only that it was permissible to have doubts about its alleged merits. Universal suffrage seemed to him to clash with obvious inequalities of talent, varying contributions to society, and differing levels of maturity. He therefore favored indirect and unequal (or restricted) voting, like what America’s Founding Fathers had thought to establish.

Unfortunately for America, the Founders’ representative government soon fell victim to the inexorable march toward mass democracy, especially with the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913, which transferred the election of senators by state legislatures directly to the people. Once established as a civil religion, democracy possessed the power, as American historian Walter McDougall has pointed out, “to conflate the sacred and secular.” Religion and leftist politics became, for all practical purposes, one and the same.

There are endless examples of this conflating of sacred and secular. The most recent is the cult that has grown up around an American black man, George Floyd, who achieved the status of saint and martyr because he died (of a heart attack according to the autopsy report) after a physical confrontation with Minneapolis police. To be sure, he was little helped by the methamphetamine and fentanyl in his system or by the irresponsible method of restraint applied by an officer. At one of several memorial services celebrating his life—a life marked by a lengthy criminal record—he was pictured with angel wings and a halo.

Concurrently, thousands of white Americans attended cultish services of repentance for their own and the nation’s alleged sin of “systemic racism.” Around the nation others, white and black, “took the knee” with heads bowed in support of “Black Lives Matter,” the religio-revolutionary movement to which all are now obliged to pay public obeisance.

Media figures do their part by their insistent demands for ever more public demonstrations of national contrition and atonement—for the removal or destruction of all monuments or names honoring Confederate leaders who stand accused of the “original sin” of slavery, and for extensive “reparations.” In this way, we are led to understand, white Americans may purchase redemption. However, even that reckoning is unlikely to pay off the alleged debt.

On Jan. 28, 1919, just weeks after Solzhenitsyn’s birth and while the Russian Civil War entered its decisive year, Max Weber delivered a lecture in Munich entitled “Politik als Beruf” (Politics as a Calling). The great sociologist had learned Russian at the time of the abortive Revolution of 1905 and had followed events avidly in several Russian newspapers. He intended to write a book about Leo Tolstoy and was profoundly impressed by Dostoevsky. Moreover, he was well acquainted with Russian emigrés who attended the Sunday discussions at his home.

Another regular attendee at those gatherings was the Hungarian critic and philosopher Georg Lukács, who had joined the Hungarian Communist Party only weeks earlier. With Lukács’s unexpected conversion in mind, Weber told his Munich audience that “he who seeks the salvation of the soul, of his own and of others, should not seek it through politics….” With civil war in Russia and revolution in Germany before his eyes, Weber concluded that politics as religion leads inevitably to violence.

Personal salvation, as Solzhenitsyn so well understood, was more properly sought along more traditional paths; this is as true today as it was in 1919.

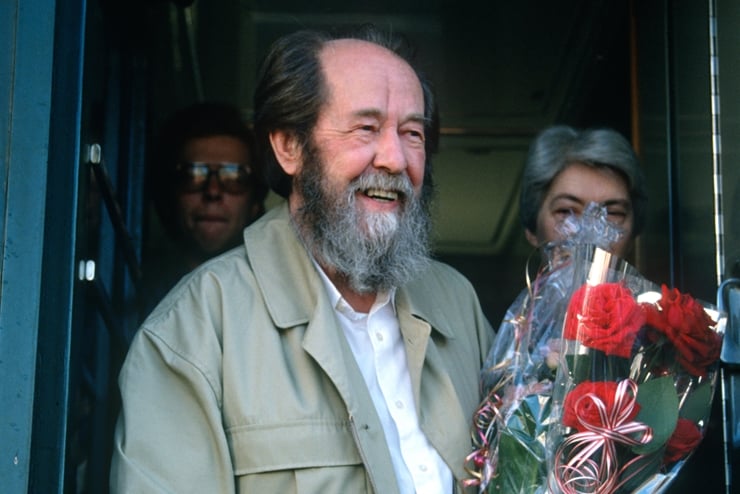

Image Credit:

above: above: on June 5, 1994 Solzhenitsyn arrives by train in Khabarovsk, Russia, returning to his homeland after 20 years of exile (Richard Ellis / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply