This article is drawn from the author’s speech on accepting The Rockford Institute’s first John Randolph Award at the historic Menger Hotel in San Antonio, a short distance from the Alamo.

For this occasion, I have been asked to reflect on “the historian’s task” and “the American republican tradition.” To do so could be a gloomy undertaking—examining two things apparently suffering through terminal illness. I shall try not to make it too gloomy.

First, let us consider that shrine of heroism nearby known as the Alamo. How should we think about it—or, rather, what is wrong with the way most Americans do think about it? We are taught to see the Alamo as one of the great exhibits of American valor. I beg to differ: It depends on what you mean by “American.” The Alamo is an exhibit of Texan valor and Southern valor. If we call it “American,” we might be tempted to think of the U.S. Army and then of the U.S. government, neither of which deserves any credit for the Alamo. Soon, we will have conflated the heroes of the Alamo with the U.S. government soldiers so eloquently eulogized by Lincoln, who destroyed the “Union” and founded the “nation” at Gettysburg. When we have slipped into this way of thinking, we have falsified the central story of American history by erecting a fake nationalist continuity of struggles for liberty. We have perverted the meaning of the Alamo, whose heroes sacrificed for the liberty of their land and their posterity.

The forces that triumphed at Gettysburg were still in the making at the time of the Alamo. But already, a significant segment of Northern Americans were denouncing the heroes of the Alamo, their fellow countrymen, as enemies—as violent frontier barbarians and pirates engaged in spreading the sin of slavery and stealing from the harmless Mexicans. These people kept Texas out of the Union for ten years. Texas finally was allowed to join, wisely reserving in her accession the right of secession. Fifteen years later, these same Northern forces mobilized two million men, a fourth of them foreigners, to destroy the liberty of Texas and keep her captive, as they openly boasted at the time, for the North’s economic benefit. At the same time, triumphant New England pundits and German 48ers used the victory to convert American history from what had been a story of constitutional republican liberty into the story of a Redeemer Nation leading the march of humanity into an ideal future of Massachusetts-writ-large.

So, let us be careful to know what we mean when we say “American history,” lest we misrepresent both history and the republican tradition. Otherwise, we might even end up, God forbid, equating the heroes of the Alamo with imperial wars against remote foreign peoples. While I am at it, let me point out the nationalist trick of adopting from the South as “American” anything that is favorably regarded, while only disfavored things are described as “Southern.” Thus, we have books on “Celtic” valor to avoid discussing the disproportionate contribution of Southerners to American heroism. We have “country” music rather than Southern music. We have Texas, when she is in good favor, denominated as “Western” and “not Southern.” In fact, historic Texas has been what she has been only because she is the offspring of Dixie. The Texans of song and story are Southerners on a new and bigger landscape. Otherwise, Texas would be just another Kansas or South Dakota of sodbusters, land speculators, and Yankee schoolmarms.

After almost a lifetime of considering what historianship is, I am satisfied that what it should be is storytelling. History is about human beings, and human beings do not live as a scientific experiment, nor as a logical proposition, nor as an ideological exhibit. Our existence is a drama, a story taking place in the mind of God. Through history, we have our only knowledge of the mysterious drama of our existence, beyond what has been granted us as Revelation.

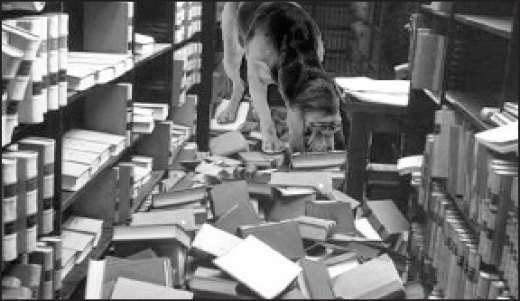

I like the delightful saying of English historian Veronica Wedgwood: “History is not a science—it is an art, like all the other sciences.” Even better, one by the great English poet and classicist A.E. Housman: “A historian is not like a scientist examining a specimen under a microscope. He is more like a dog searching for fleas.” Or, more seriously, we can make the same point by calling on John Lukacs’s perfect definition: “History is a certain kind of memory, organized and supported by evidence.” In asserting that historians do not achieve certainty, I am not denying that they may be judged according to their degree of honesty and competence in handling evidence.

If history is best understood as a story, at least two things follow. First, a story—like that of the Alamo—is somebody’s story; it is not everybody’s story, as those with an agenda, whether they be nationalist ideologues or multiculturalists, claim. Everybody can learn from a story, but, if it is to be real and valid, it has to be some people’s story. It follows that America in our time cannot have a real history, because America today does not have a real people. There was a time, peaking in the World War II era, when the inhabitants of this vast and diverse nation-state almost mingled into one people. That opportunity is now past. The inhabitants of the United States are corralled under the same territorial monopoly of force and exploitation; they share the same bread and circuses. They are not a people, only the motley subjects of an empire. Aggregations of Oprah watchers, sports fans, and mall shoppers do not a people make. After Augustus, the story of Rome ceases to be the story of an heroic and patriotic people. The Roman people pass from sight, and the history of Rome becomes only an account of more or less evil emperors and a chaos of peoples without stories. Such is America in the Era of Bush. The future history of the last national election can be written only as a meaningless contest in which the Jocks barely beat out the Nerds for possession of the imperial palace.

What is a poor historian to do if there is no core people whose story is to be told? For certain, we cannot turn to the academy. Most of the work of academic historians today can portray the American story in no other terms except those of an abstract fantasy of oppressors and oppressed. No society has ever had more professional historians and devoted more resources to historical work of all kinds—or produced more useless, irrelevant, and downright pernicious products—than modern America. I know an historian who teaches that the great Virginians of the American Revolution were like the Taliban—presumably, because they carried weapons and were not feminists. This is to reduce human experience to a paltry and partial perspective, to remove from it everything that is worthwhile and ennobling, usable and true. But this is what academic historians mostly do these days.

Second, if we accept that the historian’s task is to tell somebody’s story, it follows also that all stories may be told from more than one perspective—historians should not be engaged in categorical political and moral judgments. An historian should be trying to say something true and useful about human beings, and doing so modestly and cautiously. No historian can discover an indisputable truth, at least not about anything important. But that is what historians are claiming to do these days by reducing the drama of human experience to abstract, supposedly universal theory.

Now, because I am arguing the immutable variability of human perspectives on human experience, please do not accuse me of being a relativist or a deconstructionist. My text here is not Foucault. It is Scripture: “Judge not, that ye be not judged.”

The American Historical Association recently gave its grandest prize to a politically correct work that was later shown to be based on fabricated evidence. Then, there is Eric Foner. Professor Foner, at the time of the fall of the Soviet Union, was organizing public statements urging Russian leaders to save the noble communist experiment by crushing the Baltic peoples with the same ruthlessness, as he put it, with which Lincoln crushed the South. Foner has been elected president of both of the two most important academic historians’ organizations in the United States and is retained by the Disney Corporation as a consultant.

The sins of omission are even greater. The most important work of history published in this country in the second half of the 20th century was John Lukacs’s Historical Consciousness. It has been through three or four editions. To the best of my knowledge, it has never been reviewed or even noticed by any of the leading academic historical journals in this country. Why? Because it lies outside of the blind alley where academic historians follow their road to perdition. By the same token, if Jesus were to return tomorrow, the news media would not report the story. As in the case of the historians, it would not fit into their prefabricated pseudoreality. If the story became widespread enough, reporters would go to work to discredit the motives and sanity of those who were testifying to it. That would be the only reaction to truth of which they are capable.

History can take many forms, but I am speaking chiefly here about its most familiar form—history as the story of the nation-state—and in its American version. This history is supposed to be objective and factual, but it is also implicitly charged with a social purpose—to sustain a community with the stories of common ancestors and their legacy. As Ernest Renan remarked: “Getting history wrong is part of being a nation.” The conflating of the Alamo and the U.S. Army is a product of the nationalist history that long dominated American thinking but has now been virtually supplanted by multiculturalism. The nationalist history was fake. It was really the history of New England Yankees, and it ignored, slandered, or coopted the stories of other Americans. Early on, the “intellectuals” of Massachusetts set out very deliberately—and you can document this with great specificity—to make the American story their exclusive property. After the War to Prevent Southern Independence, their mission was complete. The proud fox-hunting Virginia planter George Washington was turned into a prim New England saint, and the heroes of the Alamo were coopted for Lincoln’s war on the South. To explore how Bostonian “American” history became multicultural/“gender” history would take many pages. I will only say that the two things are more closely related than many are willing to admit, just as debauchery and Puritanism are two sides of the same coin. But at least the old nationalist history had a limited fungibility. The new history has no redeemable value whatsoever.

It used to be that academic historians were trained by immersion in primary sources. An historian might have a bias or a theory to prove, but his first duty was to absorb the primary materials and bring back an honest summary of what they had to tell. This was a pretty good rule, and I will not deny that there is still such good craftsmanship going on here and there. But academics as a group have abandoned the search for accuracy and proportion and weighed judgment. The primary sources are there to comb for illustrations of preestablished dogma, no matter how ripped from context. What is this dogma, and where does it come from? It is an abstraction about the conflict of classes. The prevailing “mainstream” interpretations of American history today are interpretations that 50 years ago were current only in the communist neighborhoods of the New York City boroughs—except that now few practitioners are naive enough to deal only in economic class conflict. Today, they wield the much more destructive weapons of race and “gender.”

Back to my all-too-commonplace example of the historian who equates George Washington with the Taliban: It is a sadly true consequence, I think, of the dissolution of American peoplehood that the great Virginians of the War of Independence really are not a part of this historian’s story. They are really not a part of the story of most of the inhabitants of the American Homeland Insecurity today—for whom George Washington can signify little more than a cartoon character with wooden teeth. What this historian has done is super-impose on the Virginia story something familiar from his own story—the oppressors of the Old World, the Cossacks who harassed his ancestors. But that is not all: This historian has further confused things by a false theory that human life is forever and only a story of oppressors and oppressed. As a result, the czar’s Cossacks, the Taliban, and the great Virginians are best understood as equivalent oppressors. Such historianship constitutes neither a contribution to knowledge nor a useful teaching for society’s young. Such, however, is the educational regime that is being dispersed today with immense resources and the prestige of the supposedly learned. Such malicious word games destroy the chance that we, or the rest of humanity, might gain wisdom from the stories of our forefathers.

Even when it is not badly distorted, academic history has become not the remembered story of human life but only a commentary on dogma. This falsifies the vast contingency and complexity of our existence and action in time and converts it into a tawdry, diminishing determinism. It poisons the community by denying its existence apart from conflicting elements. It converts great segments of humanity into oppressors who deserve only annihilation. The result is today’s academic history—a weird combination of supposedly objective “social science” and romantic exaltation of favored minorities designated as “the oppressed.” This history fails both as accurate record and as material for social comity. As Christopher Lasch pointed out years ago, scholars have abandoned the search for reality in favor of the classification of trivia. But it is worse than that. It is in the nature of dogma that dissenters are quickly suppressed. Conformity of opinion about what is significant and true about the past has never been as rigorous among academic historians as it is today.

What, then, are we to do about our stories, and about the historian’s duty to tell stories that are true and useful? Our only hope is where it has always been found: in art—that is, imagination disciplined by honest evidence. It was observed long ago that the novel and history have a common ancestor: narrative. It has been more recently observed by John Lukacs that the two, where they are of the pure descent, may be moving together back to their origins. We already see much evidence that I could cite. It is not coincidence that the greatest history of the American war of 1861-65 was written by a novelist, the late Shelby Foote. Foote observed at the end of his 20 years’ labor that the novelist and historian are both engaged in the same work—a search for understanding—though operating by partially differing methods. The academics do not treat the works of Solzhenitsyn as history. But how could the history of the Russian people in the last century ever be told more truthfully than by this great artist and thinker?

Henceforth, American history is likely to be only the story of the rise and fall of the imperial machinery and its masters. There is no people who can cherish an American story. However, there are some remnants of peoples with stories to tell who remain in this imperial heartland: traditional Catholics and Southerners, the real Californians described by Roger McGrath and the authentic Westerners about whom Chilton Williamson writes. Let us hope that the future brings forth scholars of art and integrity to craft and preserve for these remnants their stories. For it has been truly said that we are what we remember.

Leave a Reply