“Give them hope, so they may fear.”

—The Apocrypha

There is no more Atlantis.

“Where,” I was asked in prison, by a Yugoslav State Security agent, “is this Atlantis you would like to live in, Selic?” I didn’t tell him that I wanted to live in America, it being alive and well, and still above the waters. “How many foreign divisions are there in Yugoslavia, Selic?” the agent needled me, and again I kept silent, not telling him that none were needed, him and his likes being our own, homegrown Tartars. He had never heard of Ortega y Gasset, else he would have charged him, posthumously, I suppose.

My interrogator was a defender of the will of the people, or so he felt. He, a peasant boy who had made good, and his bosses, whom the Revolution had placed in power, were ruling Yugoslavia as they were expected to. Not many polls are conducted there, but the rulers were men of acute perception, who could hear the grass grow. Much of what they did met with no disapproval, at least not statistically.

I see the dragon following me, across the ocean, carried within the heart of my knowledge. In telling, there may be a futility: customs haven’t changed much concerning bearers of ill tidings. Indifference, and the will not to see, hear, or know are still my executioners, as they were where I came from. Names had become crimes in Yugoslavia. If renaming the world could improve it, Yugoslavia would have been a heaven. They hadn’t yet progressed to calling paraplegics the “differently abled,” or to appropriating “gay” for the exclusive use of homosexuals, but they had their triumphs. Orwell was a big hit in Belgrade, as elsewhere, often with the very people who were dishing out the hogwash.

The State Security agent whose job it was to take care of me was neither horned nor fanged. As Leonard Cohen had sung of Eichman, he was merely a clerk, of destruction. He was a Protector I couldn’t protect myself from, and a computer, inputting my loss to output social gain. It was a simple trade-off in his mind, of many numbers against an entity. Before I had left Yugoslavia for good, I had talked to my friend, Srdja Popovic. A lawyer in a country where laws are regarded as impediments to revolutionary justice, he had turned his tired eyes upon me and said; “Were God meant to walk among us, why would we need the sky?” I had to smile with him then, and leave him at his task in Belgrade, for he was a courageous man, desperate beyond ability to suffer.

For life to be possible, I suppose it had to be out of reach of men, and many have written of that, including Dostoevski. Dreams and paradises when transposed to earth have an obstinate tendency to turn into hells and nightmares. There may be a dusk descending upon all of us so coddled by fortune that we have become nauseated by our own intestines. My State Security caretaker would have been delighted by the activities of various attitude police in places like London, Toronto, and New York. Among other things, he was punishing me for not being underprivileged, incapacitated, or average. He, on the other hand, was eminently average. Had he not been that, possibly he would have sat right beside me, and someone else would have interrogated us both.

My equality was to be reaffirmed by him and branded upon me, as humanely as possible. After all, he and his bosses were no terrorists, but cynical and compassionate guides into bliss. It had taken men thousands of years to articulate the idea of sin, but he was intent on abolishing it. Only one transgression was to be allowed to remain, conceptually—that of pride—while excellence and expiation were to be dispensed only by him and those who had invested him.

No nurture, I found, could turn a sable into a pelican, but my State Security godfather would have never subscribed to that. Though no Lysenko, he was committed to breeding virtue, the way Prussians effect their miraculous, square-edged hedges. If the world spurns his efforts, so much the worse for the world. He could, and would, ban any knowledge contrary to the beliefs he considered humanizing. Whether it ever occurred to him that the world went somewhat beyond humanity itself, I do not know. I suspect that it wouldn’t have mattered to him at all, for his will was to stamp his mark on everything, right down to housebroken pets and mechanized people.

Before my Eastern European, befuddled, emigre eyes, shadows flitter at high noon. Democracies have existed as long as men, as well as attempts at freedom, and the two did not always coincide. The will of the people, as Kipling wrote, may not have much to do with the way of the world, for multitudes are as prone to make mistakes as individuals. Our misconceptions, before man became mostly a computing animal, were a luxury allowed to us by our own impotence. They were paid for by those who entertained them, not by the species as a whole.

I’ve yet to hear of a committee steering a lifeboat to safety. In our days, few dictators are elected, but their proliferation should speak to us of the danger we all feel, but many fail to acknowledge. It will not be the Bomb that does us in: when Herodotus met the Scythians, they were a degenerate, obese race, on their last legs to extinction.

Everybody dies, and all things die: it is the price we pay for living. So the only thing left to us is to ensure that we have lived. The promise of life breathed upon us is as tenuous as our existence. No technology will ever be able to fulfill it, for the simple reason that no technology is ever going to be alive. If we ever succeed in breeding simulacra of life in our workshops or laboratories, we will only have completed what we have so far set out to do. Our world will have become solid-state, crystalline, and dead, to no one’s detriment but our own.

These things, unfortunately, go beyond ideology. Our search for life without its consequences, evident with Brazilian tribes as with the people in America, is the only danger we face. The communists have only turned out to be the most ferocious, devoted, and consistent hunters after safe, and deathless, life. Maybe that is the reason that their name has been tied up with so much murder and destruction.

We are killing ourselves and everything around us with our desire to live. The first outcome of our “rationalism” has been by now a permanent quantification of everything. That which cannot be counted, many have come to regard as nonexistent. But how is one to quantify love, devotion, loyalty, courage, truth, or even life itself? Nobody speaks of anyone being “partially alive,” yet I have been told, often, that Yugoslavia, for instance, is “freer” than the Soviet Union. Our ability to make such distinctions may be a good indicator of why slavery still rules the world.

Intrinsically, there is no reason why freedom should be dependent upon opportunity. Of course, Marxists would disagree with me, but I have seen men spring out of misery and meanness issue from privilege. Men have been free, and free of fear as well, in very adverse conditions, and they have been, and are, dying of fear in wonderlands of plenty. Cancer and AIDS are not our plagues, but our fear of them is. Death has no name, and cultures have differed, so far, mostly in their attitudes towards it.

What is it that forces families of Americans kidnapped in Beirut to come before TV cameras and tell us all that the lives of their loved ones are worth more than the honor, the probity, and, in the last instance, the safety of their own nation? Men have faced death since the first ones came to life; yet for thousands of years they have evolved countless ways to meet it with dignity, grace, and courage. I wonder which of those qualities are left to those of us kept plugged into life-support systems, as doctors tinker with us, making us even more mechanical than we already are.

It is the mind-set that has legislated the safety belt upon me that sees no taking in giving. Freedom is opportunity, for downfall as well as rise. In the Soviet Union, they have excised out of life all the possibility of failure by creating a unified, equitable, and universal failure. The world of seedless fruit and sinless sex will have become a reality only with the loss of our navels, which, in itself, is impossible no more.

For ages, people have divided themselves into real human beings and those who are only biologically human. But our divisions have become much more blurred, numerous, and inconsequential. Our spokespersons, representatives, and delegates to life would otherwise be out of mandate. Statistical entities, existing only in computer-degradable minds, are becoming new units of humanity—the Western experiment in the existence of the person is giving way before the ancient Asiatic reality of masses.

If biological success is to be measured by the spread of a species upon earth, we are almost as viable as bacteria or fungi. There is no reason, I suppose, why economics shouldn’t apply to humans as well. Where men have become mere fractions of millions, and billions yet to come, it is hard to envisage any other system but a collectivist one. In Montenegro, the death of every man was a loss, for the whole country never numbered more than 200,000 individuals. In India, cyclones wash away more people than that yearly, while the Chinese are apt to execute an equivalent of the Montenegrin army in a single anti-crime campaign.

Life is but a precondition to living. No place in this continuum and, I suspect, in any other, is boundless. Infinities there are only of choice, upon finite worlds. People, in their millions, spend eons watching TV, playing cards, or merely existing, convinced of their right to endless living, so they could, I suppose, have their crack at frittering away the cosmos.

In Canada, where I live, and in the USA, which I love, I see a rampant, galloping flight from the responsibility of being human. Or alive, for that matter. Our technology, economics, our medicine, and social doctrines are all working together to absolve us from the dignity of being responsible for our own lives, as well as for our deaths. Every year I find myself less free than the preceding one. Looking back upon the North America of the 50’s, I realize that it was a paradise. Freedom then had not yet become conditional upon safety—transgression was punished more severely than nowadays, while prevention was still a rightfully medical term.

Nothing in this whole wide universe is as unsafe as freedom. In fact, that could be a definition of it. Risk is what we pay with to have a chance at life. Otherwise, we would only have a chance at safety. A continent discovered and developed by those who were able and willing to risk is gradually being transformed into a playground for those willing to have us all domesticated. It was probably inevitable for us to turn upon our own selves the principles we have been using, so far, in our dealings with the world. But still it is a sorry thing to witness. I wish I were not party to it, but I am, by being alive.

There can be no adulthood without freedom, nor can there be any humanity without adulthood. For those unwilling to risk, there is always the freedom of choice, inseparable from the obligation to face the consequences. There can be no equality between freedom and slavery, ignorance and the search for knowledge, spiritual baseness and nobility. Living in this world from Belgrade to Chicago, from London to Lusaka, and from Peru to Iran, I have found it, unfortunately, mostly a place where little men base their stature upon the misery of others. Vast myriads of human beings upon this planet are united in their belief that their malfunction is a result of someone else’s success. There is no dearth of ideologues, least of all in the West itself, willing to support them in this belief There is an almost universal anti-Western, especially anti-American, feeling in all the Third World countries where I have lived. This feeling is a product of envy and injured pride.

Ideologies of jealousy are a feature of our times, more than of any other. Never before were the differences between success and failure so pronounced and obvious. That is not the fault of viable nations and societies, but an outcome of modern technology. While cursing the Satan of America, Khomeini does it by microphone in front of cameras, despite an express Islamic ban on human representation. In Kuwait, sheiks endlessly cruise the streets in their Cadillacs, fingering their worry beads and denouncing Western decadence. There are no cultures in this world but one: the culture of man fleeing nature, and the only differences are those of degree. We should not let anyone extol their impotence as a virtue. Those who rail against big power imperialism engage in petty, often much more vengeful, oppression, either at home or against their immediate neighbors.

This world is at war, and no one needs to look at a map of battlefields to see that. Beyond the borders of a very few fortunate states, homicidal frenzy, darkness, lethargy, oppression, and wholesale deception are the rules of life. Yet, among North Americans there is a blissful unawareness of the world beyond their frontiers. Even when they do travel, few travel outside beaten routes or spend time with people living in accord with their geography. We have allowed ourselves to agonize over “issues” like the right to life, a right that is mocked by each act of injustice, disability, and death we cannot do away with. We battle over women’s liberation as if all other liberations were achieved already, including the emancipation from those who would speak in the name of all of us. We talk of racial equality without ever having seen any equality, anywhere. Homosexual groups demand the right to celebrate their choice, as if it were a matter of aesthetics. We have lost the war in Vietnam and are losing the one in Central America because of our unwillingness to die for our right to our way of life. Nobody is going to fight our battles harder than we can do it ourselves. Nicaragua is not threatened by communism. We are. Maybe, for the Nicaraguans, communism represents a hope in their misery, but at least we have pulled away from such despair.

Like vacationers in a shark cage, much of the West is mindlessly taping the sights and sounds of the world as it is, outside the fragile bars. North America is still only a continent, yet to be upgraded into a planet. It must begin gauging itself by the rest of this world, instead of by its own fancies. No peace can be achieved by disarming oneself, spiritually, mentally, and physically, in the face of dangers which are formidable.

My father and my mother fought with guns to transpose the promise of life from heaven to earth. They were Yugoslav Communist Partisans in the Revolution to usher in the millennium. Both, as commissars, told their captive audiences of the coming of the New Man: noble, selfless, greedless, and cooperative. We lost most of our closest kin in the Revolution and probably dispatched many others’ relatives to oblivion. Upon hearing my father’s revolutionary spiel, his father-in-law, an incorrigible individualist and a businessman, told him: “You don’t know nothing yet!” Only my father’s intervention saved him from being shot as an obstacle to the Shining Future. Yugoslavia was the Nicaragua of its age, just as previously it had been a Lebanon. Deja vu is often merely faulty memory: as soon as he consolidated his power, Tito abolished all parties but his.

Like D.T. Suzuki, my parents saw that the world couldn’t go on in its present form. Though it had been derived from our wish to have it mirror ourselves. Dr. Suzuki’s world demands endless sacrifice: we are told that we must evolve further, to fit the nightmare of our own creation. But we cannot evolve, for we have already evolved. We arc what we are, and no amount of armed revolution or scientific tinkering is going to make us less evil, destructive, and aggressive than we are. Those who talk of the New Man, and of Changing Our Ways If We Are To Survive, are talking of death, destruction, and wholesale gelding. In our species, aggression is a means to survival; only females bear children, while males mate with them, instead of with each other. In my postwar, revolutionary, liberational time, I remember the talk of dismantling the family, to liberate us all further. The same words are to be heard today, on this side of the ocean, from people who see no abridgment of freedom in the wealth of regulation instituted at their insistence, purportedly to make the world safe for everyone. Adults do not need a safe world, but a living one. What am I to say to my children, when they are advised in school to “discuss” a blow they have received from another child? Hijackers won’t disappear if their demands are either met or forgotten. Bullies, I have learned in my Yugoslav prison experience, never strike where they don’t consider it safe, and it pains me to see America regarded as a convenient victim. If we are to survive in a form worth maintaining, we must come to grips with our humanity, instead of searching for an alternate one.

Death is a misfortune only after a misspent life. We should be thankful for its capacity to clear the ground for new life and to teach us some humility and economy. Saving our hostages in a manner that lays this part of the world open to further terror is a crime, infinitely greater than losing unwilling soldiers in a war for survival. Willynilly all of us from the West are involved in exactly such a war, and if anyone wants to know what the enemy is like, there is no shortage of illustrations. Those who have chosen to embrace any means to assault the producers of their food, consumer goods, weapons, technology, and ideology should be made hostage themselves. Berserkers should expect no quarter for their communities or those who support and goad them on.

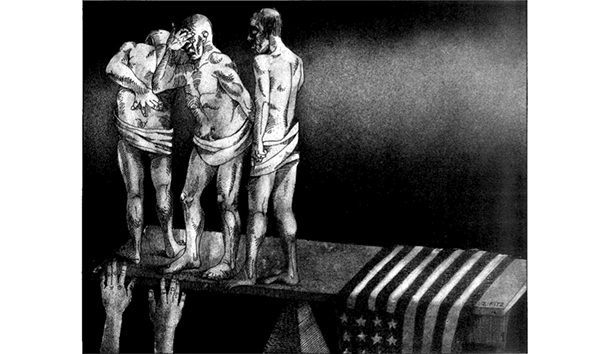

In grappling with wolves, it is the wolves who set the rules. We have all crossed the last ocean, and the only way out, now, is up. North America has built itself into a giant, promising the world a relief for at least some of its ills. It has achieved that mostly by itself and has no one to praise or blame for it. It is an island in a howling world, and the howling won’t go away through any technological, menagerial, or psychological trick. There are barbarians camped out there, waiting precisely for what is happening: for someone to open the gate, and for the men of the city to destroy themselves.

Even paranoiacs have real enemies, as it was noted on a Paris wall in the spring of 1968. Our enemies are mostly ourselves and our desire for painlessness. Khomeini, Khadafy. Hitler, Stalin, Mugabe were always merely predators. They had preyed on our weaknesses and won, at least for a time. But those are the times that determine our consciousness, the way Auschwitz determines the consciousness of a people. Good times are not what we are all about. Living hurts, but not as much as extinction. As opposed to mere death, the loss of the chance to reach our humanity is irremediable. Why do we find it so hard to understand that which is sublime in us? How does it happen that there is so much cause for evil, and yet there are good men in the world as we know it? The way things are, we might all be screaming gunmen, venting our rages upon each other.

Those should be the questions we ask ourselves. Let those who have forced us to raise them understand the Shiites, Sandinistas, communists, and other haters of this world. If things continue going the way they have for some time now, we all may live to see all our questions answered, even the ones we did not dare ask. Only, then there will be no place to emigrate, and Atlantis will again be under the sea, much heavier to emerge from than were it mere water.

Leave a Reply