Inside the whackiest state’s nonsensical plan to bankrupt itself for sins of discrimination it did not commit

Determined to maintain its lead as the whackiest state in the Union, California created its own slavery reparations commission two years ago. Recently, the commission released its recommendations, which are so fanciful, illogical, and impractical that California’s premier position as whackiest state seems assured for years to come.

That California is at the forefront of the reparations insanity is ironic for several reasons: California entered the Union as a free state with a constitution that prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude; California remained loyal to the Union when the Civil War erupted; California gold shipments were critical to Union success; and more than 16,000 Californians voluntarily enlisted to fight in the war— not an insignificant number considering California’s small population in 1860.

California’s location on the Pacific Coast kept the War Department, for the most part, from using California troops in the East. Nonetheless, hundreds of volunteers saw combat as the so-called California Hundred and the California Battalion with the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry, fighting in more than 50 engagements, many of them in the Shenandoah Valley.

Most Californians who joined the Army saw service only in the West. Altogether two regiments of cavalry, eight regiments of infantry, and two smaller units were organized in California and performed some kind of duty in the West. Some watched Southern sympathizers. Others fought Indians. Two large expeditions, one under the command of Col. Patrick Edward Connor, an Irish-born veteran of the Mexican War, and the other under Col. James Henry Carleton, also a Mexican War veteran, insured the Central and Southern Overland Mail routes stayed open.

Connor fought several skirmishes and battles with Paiute and Shoshone warriors, who had taken advantage of the withdrawal of federal troops during the Civil War to wreak havoc in the Great Basin. Carleton did the same with Apache warriors and also with Confederate soldiers in Arizona and New Mexico.

Because of the efforts of the California troops and the leadership of Connor and Carleton both the Great Basin and the Southwest remained secure and the lines of communication and trade, the U.S. Mail, and overland emigrants were protected.

Despite this history, California taxpayers, including descendants of those California troops, are expected to cough up hundreds of billions of dollars for payments to black Californians, who were never slaves.

In September 2020, the California legislature enacted into law a bill that established a “Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans.” With the governor, president pro-tem, and the speaker all being Democrats, it should surprise no one that those appointed to the Task Force are all Democrats. Of the nine members, four are black men, four are black women, and one is a Japanese-American man. All have histories of left-wing activism.

The task force issued its “California Reparations Report” at the end of June 2023. The report is a more-than-1,080-page, forty-chapter beast. Much of it is about slavery in the American colonies and in the United States in general and the conditions under which blacks lived in America following the abolition of slavery. Throughout the report California often plays second fiddle to the United States in general simply because blaming California for black suffering is difficult at best.

Individual examples of alleged mistreatment of blacks abound but there are far fewer examples of blacks being wronged by discriminatory state action. Moreover, those blacks cited for having a claim against the state often prevailed in court. Of course, that’s where all these claims should be today. There are legal remedies available to blacks but that would mean argumentation based on fact and not on assertion. Making reparations a political issue and not a legal one certainly simplifies things.

One theme that recurs in several chapters is what the authors call “over-incarceration.” It’s alleged that too many black men are serving time in California’s prisons, which is attributed to the “racist” criminal justice system. Blacks are only some 7 percent of the state’s population, it is noted, but 28 percent of the prison population—four times their percent of the general. “Over-incarceration” without a doubt—unless someone cares to look at California crime statistics, which reveal blacks commit about 30 percent of California’s homicides and other violent crimes.

Repeated, again and again, as part of the over-incarceration assertion is that “blacks are sentenced to longer prison terms than whites for the same crime.” More proof of the racist criminal justice system! Not really. When sentencing is adjusted for prior felony convictions, the sentences for blacks and whites for the same crime are virtually equal. Anyone can see this for themselves by looking at the annual report to the California state legislature by the Judicial Council of California, titled “Disposition of Criminal Cases According to the Race and Ethnicity of the Defendant.” The task force evidently didn’t bother to consult the report.

This pattern of ignoring evidence, contrary to the task force’s mission to catalogue harm done to blacks in California, is uninterrupted throughout its thousand-plus-page report. Many of the harmful actions cited could also be cited for whites. Two such examples are homeowners’ insurance rates and loss of property through the state’s power of eminent domain. Yes, blacks in crime-ridden neighborhoods pay higher rates for insurance, but those rates are not nearly as high as those paid by whites who live on the hillsides and in the canyons of the brush-covered Santa Monica Mountains and other similar areas.

Blacks have been forced to vacate their property through eminent domain but so, too, have a far larger number of whites. When I was growing up in the post-WWII era, freeway construction in Southern California was as omnipresent as smog. Most of those displaced by the construction of such freeways as the San Diego, Ventura, Hollywood, and Santa Ana were whites. A possible exception was the Santa Monica freeway, whose eastern half ran through predominately black neighborhoods. Whether black or white all property owners were given “just compensation” for the loss of their property as guaranteed by both the California Constitution and the U.S. Constitution. Now, fair market value is always subject to dispute but, again, that applies to whites as well as blacks.

Harassment by police is another theme emphasized in the report—stopped while driving black and such. This is another area where blacks think they are the only ones to have suffered harassment. I grew up riding motorcycles. The police, especially the LAPD traffic cops, didn’t quite think all motorcycle riders were Hells Angels, but they shared the general public perception that bikers were wild and probably unsavory characters and, if teenagers, likely juvenile delinquents.

If one of Chief Parker’s finest was behind me, I’d often be pulled over. Most of the time it meant not only checking for registration and driver’s license but also an inspection of the bike for any number of possible equipment violations. This could take some time—your time. Knowing the vehicle code book inside and out, the traffic cops were good at finding something they could write you for. I wonder if a black rider had been subjected to this would he have reflexively concluded the treatment was a consequence of his black skin.

I don’t expect to be compensated for the harassment I suffered as a teenage two-wheeler but most blacks in California are now eagerly awaiting a payday, some $1.2 million each, as recommended by the Reparations Report. Since they weren’t slaves in California, this is for alleged over-policing and over-incarceration, housing discrimination, unjust condemnation through eminent domain, disparities in health care, unequal educational opportunities, the war on drugs, policies adversely affecting black-owned businesses, and other such alleged harms.

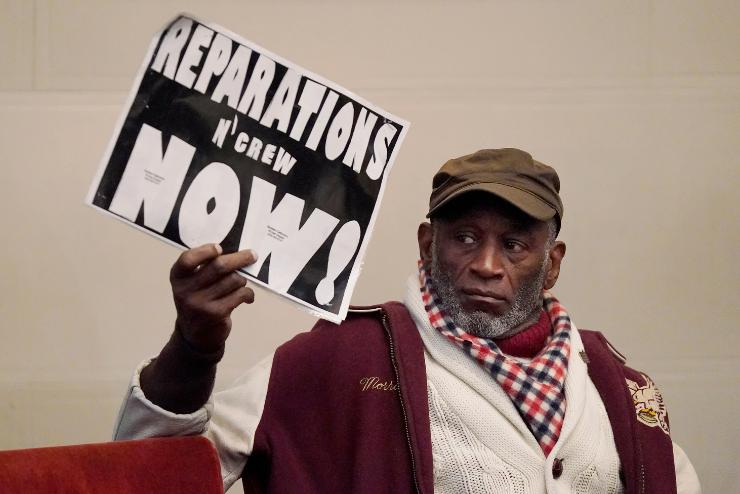

The payout would total upwards of $800 billion, which is more than two-and-a-half times California’s entire state budget. The task force members were quick to say at a news conference that the payout could be made in installments—just like the dozens of various kinds of state welfare payments and subsidies which blacks have become used to receiving in highly disproportionate numbers for generations and which have cost California taxpayers billions of dollars. But the suggestion of incremental payouts was not well received. One black woman in the audience yelled, “It’s my money, and I want it now.” Another cried, “I’m 78. I don’t want to wait anymore.”

A monetary award is only one of many remedies suggested by the task force. Other recommendations include free college education, state subsidies for black mortgages and black-owned businesses, free health care for blacks, higher wages for incarcerated labor—it’s a long list.

What I find most troubling about all this is the underlying presupposition—by virtue of being black in California one has ipso facto suffered harm, no proof required. Moreover, the state of California is responsible and the taxpayers must pay.

It’s now up to the California state legislature to pass bills to implement the report’s dozens of proposals, including monetary compensation. Since the Democrats have a super majority in the legislature, they’re likely to take some action in 2024. The only potential check on the legislature is California’s current $32 billion budget deficit and the state’s $520 billion debt, a whopping $152 billion more than New York, in second-place.

I’m sorry to say what happens in whacky California doesn’t stay in California. The state is the Wuhan lab of politics, social experiments, and cultural shifts, and the California reparations virus is certain to spread.

Leave a Reply