“We will bury you,” warned Nikita Khrushchev in the 1950’s, but in the end, it is America’s NATO imperium that is burying Serbs under the rubble of Novi Sad and Belgrade and Americans under the red tape of the New World Order.

The march of globalization has proceeded without effective resistance but not without criticism, and dissidents on both left and right have been calling for a new nationalism. This appeal has resonated with sensible people who are disgusted with the loss of economic sovereignty which has been betrayed by NAFTA and GATT, who are alarmed by the unchecked flow of legal and illegal immigrants, and who are disgusted with the internal subversion of our culture by multiculturalism in the schools and by a caste system of ethnic privileges that demoralizes European-Americans without actually helping non-European minorities.

But opposition to internationalism is not quite the same thing as nationalism, and the enemy of my enemy is not always my friend. To oppose internationalism with nationalism per se is to make a false dichotomy. It is perfectly possible to uphold the dignity of the nation in matters of trade and immigration, while at the same time belonging to an international religion like Christianity.

Christians who oppose the New World Order may also believe that the national government has far too much power over the states and cities where real life is lived—outside the Beltway and a half day’s drive from Saltwater—but they are not necessarily prepared either to declare that the nation is everything or to deny that it is anything at all. Christians ought to be deeply suspicious of nationalism and globalism, both of which developed in the course of the 18th century and were advocated by the bloody-handed leaders of the French Revolution who killed each other over whether the Revolution represented the revival of the French nation or the dawning of the brotherhood of man. In the end, the nationalists won, and while Napoleon pretended to be liberating the captive nations of the Holy Roman Empire, he was really only replacing Austria with France, Habsburgs with Bonapartes. Stalin and Trotsky played out the same homicidal farce in their struggle for control of the Soviet Union. Again, the nationalists won out, as they did in Germany, Italy, and the United States, each nation creating in the 1930’s (as James Burnham and John Flynn observed) its own form of national socialism, which became the dominant form of government in developed nations like the United States, Sweden, and Israel as well as in most Third World countries, where a series of strong men—Peron, Nasser, Qaddafi, Mobutu-combined welfare policies with aggressive nationalism.

Classical liberals and libertarians, in criticizing the new nationalists, take their stand on the individual and defend economic liberty against what they call “protectionist” legislation. They may oppose, as Paul Craig Roberts does, the World Trade Organization and write critically of NAFTA, as Llewellyn Rockwell has done, because those schemes are not truly instruments of market freedom; but in the end, classical liberals object to any economic plan that increases the power of a national government to interfere in the market choices of individual citizens. While they often, if not always, go too far in their advocacy of markets over families and communities, libertarians and classical liberals are not wrong to remind us of the dangers of governments which may speak the language of national interest but more often cater to their richest and most powerful clients.

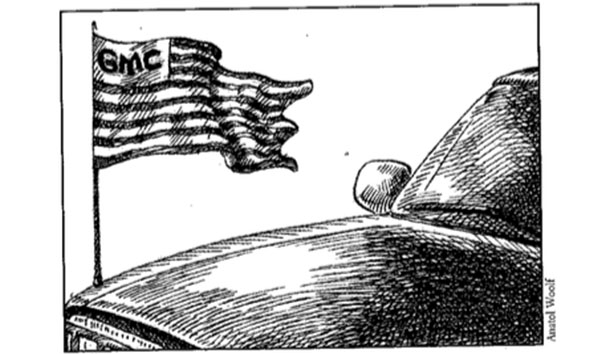

“Nationalism” has often been used as a rallying cry for special interests who identify themselves with the nation. There are businessmen who still believe that “what’s good for General Motors [or Microsoft] is good for the nation,” and there are nationalist political leaders who have divided the Western nations against each other and made alliances with the sworn enemies of Western civilization. There is no need to cite France’s support of the Turks against Austria when it is just as easy to bring up the series of wars, nationalist revolutions, and nationalist/fascist movements that have set the English and the Germans at each other’s throats twice in this century and even divided nations against themselves. The fact that nationalisms often sow the dragon’s teeth of discord between a nation’s citizens should be of some concern to nationalists who oppose regionalist movements on the grounds they are divisive.

But far more significant than the European bloodbaths or the ethnic and religious antagonisms of a divided France (or of a divided America) is the tendency of American nationalism to cut us off from [he broader civilization that we are part of, that we must be part of, if we are to avoid sinking into barbarism—or worse. After all, other barbarian and savage peoples (such as the ancient Germans and the American natives) had evolved their own cultural, moral, and religious traditions over a period of millennia; we Americans, on the other hand, have only consumerism and materialism to fall back on.

Some nationalists are fond, it is true, of appealing to the solidarity of people of European ancestry, and there are little journals and cliques of Euro-American activists who draw up lists of ethnic slurs against the Irish or the Poles or against white people in general. “Euro-Americans, Unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains”—and nothing to gain but the ethnic hyphen which functions as the “de” or “von” of the old nobility.

Before rushing in to join the chorus of complaining minorities, perhaps we should pause a moment to reflect on what the future may hold in store for us if a Euro-nationalist movement succeeded. To stand up for your family, kinfolk, and people is a natural and wholesome activity; to become obsessed with what some out-group has done to you—whether they are Jews, immigrants, or blacks—is to lose part of your humanity.

Polarization can also be a problem for regionalist movements like the Lega Nord in Italy, which sometimes manifests a barely concealed contempt for Italians from the South. Since the Northerners conquered Naples and Sicily and forced them to become part of an amalgamated Italian kingdom, the attitude is hard to justify What is worse, some North Italians now like to think of themselves as Swiss rather than Italian. This is not only an ethnic fairy tale, but it also tends to alienate Northern Italians from the brilliant civilization that all Italians can claim as their birthright. Some of these Italians-who-would-be-Swiss are like the American racialists who watch reruns of Conan the Barbarian and despise the Mediterranean peoples who created our civilization. “Better white than right” is their motto.

The Lega’s strongest argument is regional diversity. When Italy was broken up into hundreds of separate quarreling states, it produced the greatest civilization on earth since the ancient Greeks, who also lived in warring city-states. Unfortunately, the divisions in Greece made them prey to the Macedonians and the Romans, and the Italian states were repeatedly invaded and subjugated by Spaniards, Frenchmen, and Austrians. A Lombard in 1800 might well desire the unification of Italy on exactly the same grounds as his descendants today use to justify its breakup.

It is a mistake to be doctrinaire on questions like secession, trade, or foreign intervention. Pat Buchanan has gone from free-trading Cold Warrior to peace-loving protectionist. In reality, Buchanan has always been a patriot, neither more nor less. When most patriotic Americans thought the primary challenge to American freedom came from the expansion of communism, he was a strong interventionist. After the end of the Cold War, when the main threat came from globalization, he had the insight and agility to turn around and face the new enemy. This is not nationalism per se (as some of his overzealous advisors are claiming), but only a prudent defense of the country that he loves.

Many writers have distinguished between nationalism and patriotism, but they do not always make a coherent and convincing argument. If we begin with the words, however, some obvious differences do emerge. Patria is the good old word for homeland—Greek, Latin, and in German as Vaterland. It is the land of one’s fathers and the land whose traditions and customs and rules represent a kind of paternal authority’, whether power is exercised by the king or by a parliament.

The Latin natio, derived from the verb nascor (“to be born”), originally signified birth and then came also to mean people connected by blood: a tribe or race. If patria is primarily a social and cultural concept, natio is essentially biological and racial. As an English synonym for homeland or country, “nation” enters rather late in the game. The OED lists the first occurrence in this sense as late 17th century but adds “rare.” When “nation” is used to mean country, it almost inevitably implies the desire to unite the scattered fragments of the nation into a single state and, by extension, to suppress alien nations within the nation-state.

The older concept of patria, while not immune to ethnocentrism or territorial ambition, has a different flavor. It was quite possible to be a good Czech who loved his country while at the same time being loyal to the Hapsburg empire and willing to get along with his Slovak and German neighbors. A Czech nationalist, however, would work to unite the Czechs into a single state, expel or subjugate the Germans, and compel the Slovaks to adopt the Czech language and Czech culture—which is exactly what happened in Czechoslovakia between the two world wars and, to a lesser extent, after the collapse of communism. One nationalism always begets another, and the Slovaks are now independent.

In the United States during the 1850’s, there were patriotic Yankees who loved New England, were loyal to the American republic, but took a live-and-let-live approach to the South. Nathaniel Hawthorne was of this type, as was his friend President Franklin Pierce. Increasingly, however, as a Yankee-U.S. nationalism developed, it spawned venomous anti-Southern, anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, anti-black movements—the Know-Nothing and Republican parties—that in turn inspired the Southern nationalism that made the crack-up of 1860 inevitable. Ever since, U.S. nationalist politics have suffered from an ugly strain of chauvinism, eugenics, and—more and more—a revanchiste spirit against various minority groups.

Teddy Roosevelt, the great nationalist, racist, and eugenicist so much admired by the editors of the Weekly Standard, said there could be no 50-percent Americans—no “Jewish-Americans,” for example—only 100 percenters. And the example of TR, who shamelessly promoted America’s conquest of the Philippines, also proves how easily nationalism slides into imperialism.

Christians usually end up being a main target of nationalist ideology, and the most powerful and successful nationalist movements of the past 500 years have nearly always grown at the expense of either a specific Christian establishment or of the Christian religion in general: Elizabethan England was built out of the ruins of the monasteries; the French Revolution nationalized the Church and then turned it into the cult of reason; the Italian government, during the Risorgimento, expelled the Jesuits, confiscated monasteries, convents, and schools, and persecuted the Church.

In pluralist America, we have been comparatively safe—though some nationalists of the 20’s and 30’s tried to shut down religious schools—but liberal nationalists today have eliminated school prayer and tried to push all vestiges of religion out of the public square. There is no reason to believe that Christians would fare any better under a right-wing nationalist regime; they certainly did not do well in the Third Reich.

There is little left of the old American patria of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, and the national culture represented by Mark Twain and William Dean Howells, Henry Adams and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, is as foreign to us now as medieval Provence. Any attempt to create or impose a national culture will be a dangerous exercise in fascism that would end up destroying all the little peculiarities that give American life its savor.

Then what is to be done? Right-wing nationalists invite us to invent a white or Euro identity as artificial as the euro monetary unit, to establish it in schools and in the media at the expense of regional and foreign cultural identities. To heighten the national sense, other groups will have to be denigrated, their languages and cultures outlawed, and the reinvented nation—to prove its mettle-will embark on a series of imperial crusades to Americanize the world.

Patriots would agree with the nationalists in pressing for immigration control, rejecting multiculturalism, and recognizing the dominant religious/cultural traditions of the old America, but they would leave authentic traditions alone. (Even the Front National recognizes the historical and cultural importance of the regions of France.) Above all, the patriot would not waste his time castigating people outside his country’s traditions but would concentrate on rebuilding those traditions—of literature and art, of manners and morals, or (to drop down to the lowest level) of sanitation and the rule of law. Celebration and cultivation would be the dominant note, not denigration. This is exactly what I do not sec in nationalist publications such as the Weekly Standard or American Renaissance—two groups that resemble each other more than most people suspect.

The highest patriotic credo used to be summed up in the phrase: “My country, right or wrong; and where it is wrong, set it right.” Conservatives of every stripe have spent too much time complaining about what other people have done to make our country wrong. Perhaps we should leave the whining to the brownshirts and the neoconservatives who know only how to hate and set about the task of making our country right.

Leave a Reply