The statistics that break down the consumption of music into types and groups are not very comforting to consider. But if we really want to know what the musical situation is, rather than to entertain a fantasy of what it ought to be, we would have to acknowledge the realities of musical art in our postmodern age of digitalization. With so much easily available, the public demand for “classical music” and the fans of jazz together constitute roughly five percent of the music trade. That may explain a few things about what everybody knows to be true: There has been a collapse in the position of serious music.

That would mean much about the status of orchestras, opera houses, and choral institutions. That would mean that National Public Radio only feebly waves a flag at which few salute. That would mean that the people from whom jazz was developed don’t listen to it, by and large. And the situation means more.

The celebrity that was formerly accorded to such musicians as Arturo Toscanini, Leopold Stokowski, Jascha Heifetz, and Leonard Bernstein is not likely to be seen again. Walt Disney was a success, in a manner of speaking, as a vehicle for uniting elite values with popular ones, or highbrow with lowbrow. If we lived once in a situation in which Stokow ski and Mickey Mouse could get together, that challenged unity is but a dim memory.

The tutelary talents and obsessions of Leonard Bernstein were remarkable in their time; and though there are contemporaries who have a broad reputation today—Hilary Hahn, Thomas Hampson, Renée Fleming, and others—there is something about the centrality of the best music that is gone. And such names as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Ella Fitzgerald stood for musical mastery in their time, in just about everyone’s mind, but I doubt that many today could nominate various accomplished jazz artists. To see in this falling off a “development” or “change” or anything but a cultural lapse is to concede too much altogether to contemporary smugness.

Even so, we should be cautious or even skeptical about the good old days. Perhaps we could address the matter of cultural decline by digressing from music to another form of art. We could think about prose fiction, for example, but perhaps more productive would be the topic of film. In this case, we are talking about a phenomenon that was developed in our own country, rather than being imported preformed, like European art music.

Now in one aspect, music was always a part of the film experience, even before the end of the silent era in 1927. Hollywood did not hesitate to exploit the heritage of music, the performers, and even the composers in its relentless pursuit of profits. Some realized early on that the medium of film was a powerful phenomenon, and that it also was a new art form. The early critics of film saw to it that whatever could be respected in moving pictures was recognized: technical advances, political implications, aesthetic achievement. But just as Hollywood was bold and smart enough to seize control of the evaluation of its own product through the Academy Awards, the studios made sure that there were more bad movies than good ones. They owed it to the public! And they were rewarded with wealth beyond the dreams of avarice, but not beyond the purview of the government that challenged the “vertical integration” of the studios. The golden age ended as the breakup of the cartels and the advent of television changed everything, in the late 40’s and the early 50’s. The creative destruction produced perhaps the best years of Hollywood, but let’s not get too broken up about it. There was always a lot of bad art in our country, and bad music was only one kind, one channel of cultural degeneration related to others.

To put it bluntly, Moby-Dick (1851) was not exactly a big hit in its day—and what was a big hit, you might not wish to know or, at least, not want to read. But perhaps another analogy might be more pertinent somehow. Gidget (1959), starring Sandra Dee and James Darren, was more representative of its time than Melville’s masterwork was, in more than one sense. For one thing, Gidget proved that teenage anxieties were themselves a money-making proposition—Gidget was a trend-setter with progeny, and what could possibly be of more grave importance than that? Millionaires made millions by floating soft porn to kids who ate popcorn.

Where the Boys Are (1960) remains a remarkable example of the lurid puritanism of the American imagination: This trashy soap opera flaunts the sex it flashes, while condemning its dangers; the film is actually nuanced, a good movie in its way. The subsequent reality of Dolores Hart as Mother Dolores Hart is a challenging fact and not a joke, and is no more deniable than the particular talent of Paula Prentiss. Wherever the boys are these days, their incarnation in 1960 seems like something long lost, especially from the disgusting remake Where the Boys Are ’84.

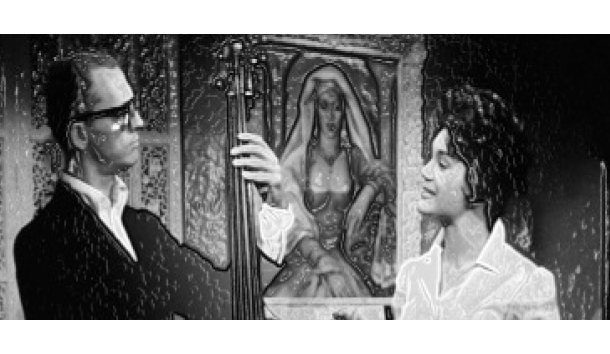

Compared with what followed, Where the Boys Are was an achievement, as when there appeared a comic character who plays “dialectic jazz,” which would be incomprehensible to today’s youth. But there is no telling what Americans can do when they get going, and so we must review some years and titles and think of all the damage and all that money and all the wasted time.

By no means complete, even a preliminary run-through of the basic sand/swimsuits/surfboards/lousy rock music/just let the camera run tours de faiblesse will speak to our cultural heritage as few phenomena can. Did anyone suspect what Beach Party (1963, with Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello) was going to lead to? Well, I’ll tell you what it was going to lead to: Back to the Beach (1987, with Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello)—that’s what it was going to lead to! There may be a pattern here. But it was a long time coming, and even then, there was Annette’s serious problem with multiple sclerosis and her death in 2013. But back in the day, there seemed to have been an alternate reality to war, assassinations, riots, and other challenges to complacency.

In 1964, there was Muscle Beach Party, with Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello; Bikini Beach, with Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello; Pajama Party, with Tommy Kirk and Annette Funicello, not to mention Elsa Lanchester and Buster Kea ton; and For Those Who Think Young, with James Darren and Pamela Tiffin, remarkable even for this sort of thing. Therein, the discrediting of the song “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms” had a knowing quality—on screen, the song was rejected in favor of a striptease act by the challenged singer, Tina Louise. The reversal of values was explicitly endorsed, with no acknowledgement of John McCormack’s superb recording of the quaint old thing—his mastery is pretty much unimaginable to contemporary youth and adults.

In 1965, there were Ski Party, Beach Blanket Bingo, and How To Stuff a Wild Bikini, each with Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello. In 1966, The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (with Nancy Sinatra and Claudia Martin) said something about a series that might have lost its way, if it could have been said to have one.

But then perhaps the point is made. The commodification of culture is as inexorably destructive as Karl Marx said that capitalism was. And so returning to the musical subject, we see where we stand, or rather don’t stand. And now we would have to add to the dizzying mix of commodification the digitalization of information, in order to realize that there will be no mercy spared to musical art in the continuing revolution. If the power of film has been abused just a little bit by commercial interests and lazy and segmented audiences, the power of music will not be spared any degradation or vulgarization, as it is exploited politically, socially—in every way possible.

And there is another way, as we have become used to, which is the association of various strands of music with identity politics. And this is yet another destructive and dangerous exploitation, and certainly a mistake, though also a premeditated one. The beach movies of the 60’s, with the prim slickness of their calibrated prurience, could not be made today for several reasons: some racial, some pornographic, and some campy.

Yet those same beach movies are a valuable reflector of what has happened to music in the imagination of the nation at large. The phenomenon of the segmented market has destroyed whatever cultural unity the nation had known. When Henry Fonda, as Tom Joad, said goodbye to his mother at the close of The Grapes of Wrath (John Ford, 1940), the last three scenes were sealed with a musical reference that the audience effortlessly understood—the phrase “square dance” was not ironic then. For today’s youth, there would have to be an explication of the obscurity that was once obvious: “From this valley, they say you are leaving. . . . Do not hasten to bid me adieu,” etc. But between 1940 and today is 1959, when Johnny and the Hurricanes had a hit with “Red River Rock.” So much of today’s values are based on destructive mockery.

Alone in the dark, with even the former popular culture of the country cast off, the “consumer” today has to create his own reality, by what he cultivates or collects or commemorates, and also by what he avoids. And this will be so both for people whose values are familiar and for those whose values are not.

The paradoxes of highbrow values in a lowbrow world of commodified exploitation are the challenges of our unstable environment. The individual will have to make his own way in all the confusion and degradation. But one thing is sure: Though there are joys to be treasured, some famous and some arcane, never before has youth in itself had so little reason to be valued. Restoring youth to its proper place in the scheme of things is a challenge, a necessity, and even its own reward. And one mode of this restoration is unmistakably a musical one.

Leave a Reply