This was the first time I’d gone deer hunting alone. Granted, I had often engaged in the act of hunting by myself. Ever since I was old enough to hunt apart from someone else, my practice had been to split up from the others after a brief initial hike. Even though we might be separated for a time, there were always stories to be shared back at camp or during an accidental meeting in the woods. This year, there was no camp, and I had no companions.

The camp eventually known as The Animal House was established only in 1961—a relative latecomer to the scene of the great Northwoods hunting camps. It was not a “camp” in the sense of a privately owned piece of land with a cabin; instead, it was a site in the Ashland County Forest of Northern Wisconsin, on which a tent would be temporarily erected each year. My father began hunting there in 1962, after leaving the military. Different people came and went during the early years, but the number had stabilized by the time I joined in 1984, as the fifth and youngest member. We formed a consistent crew for decades to come.

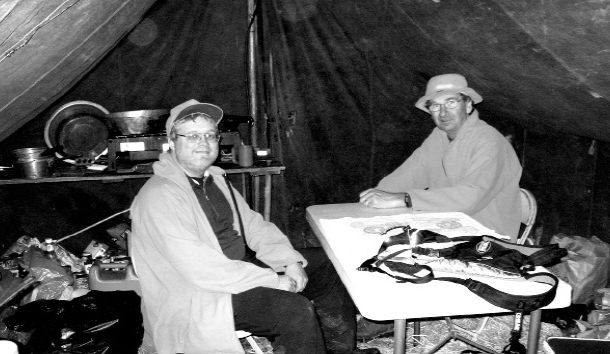

There was a time when tent camps were not uncommon, but even by the 1980’s, ours had become a notable anachronism. When you told someone you’d just met that you hunted out of “the tent,” that was sufficient. There was no other within the vicinity. The occasional passersby on the fire lane, when they stopped out of curiosity, invariably expressed surprise at the warmth we were able to maintain inside the tent.

The tent itself was actually two old canvas military tents joined together. In later years, my friend Franz added a portable canopy out back for his barbecue grill. I jokingly called the addition “the gazebo.” The name stuck, and we eventually integrated the canopy into the front of the tent, using tarps along the sides to transform it into a sizable vestibule. Heat was provided by a large wood-burning stove, exhausted through a hole in the tent, provided we kept the damper and stovepipe cleared of creosote.

Clothing hung from the ridge pole of the back tent, with the rising heat easily able to vanquish any dampness in them. Socks and boot liners hung below special eyelets in the front-tent ridge pole, immediately adjacent to the wood stove, on clothes hangers that had been mangled to an appropriate shape for just such a purpose. Our mattresses and sleeping bags were kept off the straw on the floor by plywood bed boards. Over time, most of us adopted some sort of cot, which not only added a significant amount of under-bed storage space but elevated us into the warmer altitudes of the tent.

In fact, the tent was so comfortable that we spent a great deal of time there over the week of Wisconsin’s gun deer season. We would get up late, eat a large breakfast, and go out into the woods in the latter part of the morning. Although the old-time deer camps had a reputation of partying hard at the bars, of which small Northwoods towns had no lack, we went into nearby Glidden—40 miles south of Lake Superior—once during the week, to buy steaks at the grocery store and to have drinks at the Northwestern Bar, so we could use their telephone to call home. The Northwestern Bar was eventually torn down to make room for a gas station, which now sits abandoned. Indeed, all but two of the taverns in Glidden have closed, along with the drugstore, the grocery, and other miscellaneous small businesses.

From 1957 through 1979, Wisconsin had a “party permit” system that effectively viewed the deer camp as the fundamental building block of deer hunting. In addition to buying their own buck tags, a group of four hunters could apply for a single either-sex deer permit for themselves, as a camp. Not only did this policy give the state a tool to manage the deer population that was less drastic than issuing either-sex or antlerless permits on a large scale, it reflected the social bonds that brought hunters together. Even when the “hunter’s choice” application process was introduced in the 1980’s, the practical result still ended up being that, in many years, at least one member of our camp would receive an either-sex tag, thanks to the way the issuing system was staggered. This at least sustained the potential for a de facto party permit arrangement through another decade.

In the late 1990’s, the state of Wisconsin instituted a special “temporary” season to reduce the number of deer in certain farmland areas. Under pressure from insurance companies concerned about car-deer collisions and agricultural interests looking to minimize crop damage, the Department of Natural Resources subsequently expanded “T-Zone” hunting during the 2000’s. Such special seasons were applied to deer-management units across large portions of the state, with hunters receiving free bonus antlerless permits as an inducement.

This was extremely unpopular with northern hunters, because it started to make large dents in herds that, at least in the Northwoods, weren’t actually all that large. A friend who lives in the area complained at the time that he saw all kinds of people show up for the early season who had no historic connection to Glidden. They would harvest deer and leave, not to return in November. He asked one such person, “Why are you coming up here for this T-Zone hunt? There aren’t that many deer up here.”

“We don’t want to kill all of our deer,” the man replied. He meant the deer in Central Wisconsin where he hunted during the regular season.

The T-Zone hunt and other special seasons devastated the traditional Northwoods deer camps not only by allowing others to harvest the deer in excessive numbers but by killing them in October, far ahead of the traditional opening day. As a surviving bar operator complained to me, between the T-Zone, the youth hunt, the extra permits, and the wolves, the deer were being pushed hard for months on end, and that was hurting the businesses of the area, which used to depend on Glidden’s reputation as a place to go for big bucks. “The DNR is crazy,” she said. “They want to wipe out all the deer.”

Wolves, in particular, are a sore subject in the Northwoods. Some of this is because of concerns about the danger to pets and other animals, but wolves also hinder the ability of the deer population to recover from winter losses. As the Associated Press reported with regard to the 2015 season, “The DNR has imposed prohibitions on killing antlerless deer in 12 northern counties where the agency is trying to rebuild a herd thinned by harsh winters and predators such as wolves.” The wolves are believed by the people in the area to have a significant negative effect on the local economy through lost hunting-related business stemming from the decline in available deer.

Furthermore, during the first ten months of 2015, before gun season, the DNR listed seven cases of “verified wolf harassment or threats” involving a “health and safety concern,” of which five occurred in northern counties. The other two incidents took place during the fall in a Central Wisconsin wildlife area, with hunters in both cases having to discharge firearms when wolves came within five feet, apparently intending to attack. In spite of legitimate concerns about wolves and the need to manage their numbers, the hands of the state have been tied by a federal judge who barred the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from removing the gray wolf from the endangered-species list.

Nevertheless, there have been opportunities for improvement at the state level, especially following the election of Scott Walker as governor in 2010, since he’d made deer management a campaign issue. In particular, the Wisconsin Hunters Rights Coalition characterized the so-called Earn-a-Buck program and the October T-Zone hunts as “unpopular practices that have undermined the culture of deer hunting, caused hunters to quit, and took the fun out of deer camp.” These abuses were overturned by the legislature in the wake of Walker’s victory, but much damage had already been done. Even after the reforms were passed, harsh winters further depleted the deer populations, especially in far Northern Wisconsin, as well as in the neighboring Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

In 2000, when the T-Zone hunts were put in place practically statewide, Wisconsin had a near-record number of licensed gun hunters (694,712, second only to the total in 1990) and a record number of 528,494 deer killed, of which 361,264 were antlerless. During the seasons that followed, both the number of hunters and the number of deer killed gradually declined, as people began to perceive a negative impact on the quality of the hunt. By 2014, the number of licensed gun hunters statewide had fallen to 609,779—the lowest level since 1976—and the combined gun-season deer kill of 222,588 was the second-lowest since 1983.

The vast majority of the gun deer harvest occurs during the nine-day season around Thanksgiving, accounting for 199,583 animals statewide in 2014. Only 613 deer (0.31%) were killed in Ashland County that week. The situation stabilized somewhat across the state as a whole in 2015, with the total gun kill increasing by a paltry 143 from the previous year. Nevertheless, just 568 gun kills were registered in Ashland County for 2015, and a mere 496 (0.24%) of those deer were taken during the traditional Thanksgiving-week season.

The disproportionate impact on the tenuous economy of the Glidden area has been very apparent. The local six-room motel had vacancies all week. At the bar, the proprietress told me that 2015 was the seventh year in a row that the number of seasonal customers was down during the week of the hunt. A friend active in the local VFW noted that the post had made more than 500 dumplings for their Friday night pre-season dinner, but based on consumption, he estimated that attendance was down by about 40 people from the previous year. The waitress at the local restaurant concurred, saying on the evening of the opener that she figured they were on track to be down about three-dozen people, and listing a handful of camps she knew were no longer coming up to hunt. By the middle of the season, the toll was being reported on the front page of the Glidden Enterprise:

In talking with a good number of hunters, not only are they not seeing any bucks, a majority are not seeing any deer—Period. . . . It was quite noticeable that this year’s hunting season would have less [sic] hunters going out in the woods for as long as anyone can remember. Mid-day on Friday was a light traffic day compared to years gone by. There is [sic] several traditional deer camps in our four-town area that remained “Closed For the Season.” I don’t think we will hear “Wait ’til next year.”

Our crew did not bait, drive, or climb trees. We just walked individually, looking to catch sight of a deer or to get on the tracks of one—hoping for a brief opportunity to get off a shot. We might only see a handful of deer in a season. In more than 30 years of hunting, I killed exactly one antlered buck. I’ve always been fine with that.

The real reward was in the shared camp experience—the long drive (for many years done overnight), setting up the tent, cutting firewood, and preparing meals. It was in the recounting of the day’s hunt, whether in a chance crossing of paths in the woods or at the end of the day, while eating peanuts and throwing the shells on the straw-covered ground under the tent. There was even reward in shared adversity, ranging from water coming in the tent to stovepipe fires to vehicle or weather-related problems, because each offered the opportunity for bonding and a new story.

In recent years, a combination of issues—mostly arising from ill health and aging—whittled away some members of the camp and made it difficult to plan for a week-long tenting experience. With fewer people hunting for fewer days, and uncertainties as to who might be able to go in a given year, the tent gave way to staying in a motel. We were no longer in our canvas paradise, but we still drove together, stayed together, and reminisced about our days in the camp.

Last year, I was the only one who made the trip. I don’t think everything has ended yet, because I know one of the others plans on trying to come back. However, I had plenty of time alone in the woods to think about the future, and what happens when the men of the generation before me are no longer able to hunt.

I have three children, but they are several years away from being old enough to hunt. By that time, all of the other members of the camp who have hunted during the last decade will be in their 80’s. When I was 12, I joined a thriving camp in which the heavy lifting was already being done by other men in their prime. I don’t know how I could, by myself, set up and run a tent camp with a wood stove while teaching three young girls how to hunt, and make the week enjoyable for everyone. Even if there is a practical answer, I have to believe the experience will be very different.

Of course, even pursuing that line of inquiry assumes the children would want to hunt. I don’t know that they will, by the time they reach that age. A lot of participatory activities are declining, as the virtual world of amusements has taken hold, especially among younger people. As the proprietress of the bar lamented, “People don’t need to come to town anymore, now that they can do business on their phones.” That helps explain the long-term trends that work against the revival of small, Northwoods retail businesses, even among a potential customer base that lives there, but it also surely plays a role in suppressing the flow of seasonal customers, if staring into electronic devices has become more appealing than staring into empty woods.

In an AP article published at the beginning of the 2015 deer season, Jeff Schinkten, the president of Whitetails Unlimited, recalled, “There was a time in my life when hunting was so important schools would shut down. It’s not that same old world I lived in in the good old days.” He added that a lack of available deer made it less likely that marginally interested people would develop or sustain an interest in hunting. After all, if someone judges the success of his hunting experience by his ease in shooting a trophy deer, why would he want to come all the way to “big buck country” to see nothing but wolf tracks for a week, when he could go somewhere else or do something else? I’d like to think my children will be different, but it seems prudent not to make too many plans based on being able to prop up their enthusiasm for an activity that requires a lot of work, with no instant gratification.

If I want to make a change of location, perhaps with an eye toward maximizing the possibility of getting my children interested in hunting, now is the time I should be considering it. Yet I’ve invested more than 30 years in one particular area. As I told a friend, “Even when I get lost, I kind of know where I am.” In addition to places that have actual, recognized names, I know “Scopeses Clearing” (a double plural used by another hunter in that spot, long ago, in reference to his rifle scope), “Gut-Pile Woods,” “Elmer’s Place,” the “Bowling Alley,” and a lot of other nomenclature that may not have any meaning outside our camp, and whose significance will be lost when the last of us is gone.

On the final day I hunted, I saw a deer. I couldn’t shoot at it, because I couldn’t positively identify its sex, and I don’t think it was a buck. Still, it made me feel I’d had a successful hunt, and the more time I spent in the woods, the more my longing for the old camp was pushed aside by the enjoyment of the experience. A few days earlier, my wife had called to say she and her relatives were concerned about me being alone in wolf country, and they wondered why I would want to keep going back to a place that had relatively few deer. My answer came reflexively: “I always hunt here. It’s what I do.”

Leave a Reply