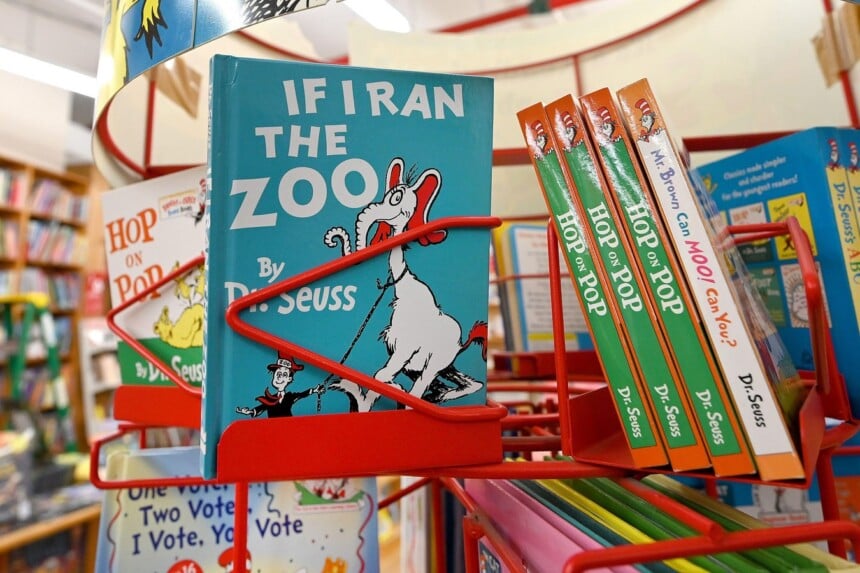

Just when we thought cancel culture couldn’t possibly get sillier, new heights of inanity were achieved in March when Dr. Seuss Enterprises removed six of that author’s best known titles from its active publishing list upon recommendations from a “panel of experts.” Among the titles canceled for racial insensitivity was the delightful If I Ran the Zoo.

Ah, yes. Those inescapable panels of experts! One suspects that the audiences consulted by Dr. Seuss Enterprises in their decision did not include any children.

Conservatives are too apt to think of cancel culture as a kind of cultural Mad Cow disease that has descended upon us without rhyme or reason—the most salient symptom being a frightening, frothing-at-the-mouth hatred of everything we hold dear. But the defenders of cancel culture do have arguments, and however wrongheaded those arguments may be, they are not entirely irrational.

One of the most prevalent of these arguments is that cancel culture is a manifestation of democracy—that is, a form of democratic activism which seeks to hold individuals or companies in positions of power accountable. According to Aaron Freedman of The Washington Post, critics of cancel culture have “contempt for democracy.” Cancel culture is not, he argues, primarily about anonymous censors on the internet, but about “the public and democratic engagement of ordinary people.” That certainly sounds like something most Americans could enthusiastically support, right?

If cancel culture were mostly about ordinary people seeking accountability, then, yes, we would have far less reason for concern; but “flash mobs” exercising their anonymous muscle on the internet or hostile groups shouting down speakers on college campuses or pulling down monuments have little or nothing to do with accountability. Yes, cancel culture may be seen as a form of democratic action, but its defenders fail to acknowledge that it is the most degraded form of democracy: mob rule.

Plato feared democracy precisely because of the potential for mob rule, and James Madison condemned the threat of “factions,” which he described as groups “united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.”

Moreover, defenders of cancel culture rarely acknowledge the degree to its initiatives are generated or abetted from the top on down: by social media moguls, by corporate and academic administrators, and by the aforementioned panels of experts. In our managerial state, mob rule increasingly provides a therapeutic outlet for the unruly, and is tolerated or encouraged, especially when the mobs demand state-sanctioned solutions to real or imaginary problems, thereby expanding the endless intrusiveness of state bureaucracies.

Corporate entities like Facebook, Disney, or Dr. Seuss Enterprises work hand-in-hand with the state. In the case of the latter, the titles recently canceled were said to contain dangerously racist stereotypes. If I Ran the Zoo contains an image, which fans of Dr. Seuss will recognize as the one in which the “tizzle-topped Tufted Mazurka” is removed from captivity by two natives of the “African island of Yerka.” It is true that the natives in question, with their enormous nose rings, bloated bellies, and tribal hairdos, are caricatures that vaguely resemble “comic” images of Jim Crow-era black picaninnies. But a close look reveals that the design of the bellies and hairdos almost perfectly mirrors the shape and appearance of the Tufted Mazurka. The image is clearly not intended to provoke a racist response. Besides, everything in the world of Dr. Seuss is caricatural; that is the genius of his art.

The common sense question here is, if the publishers of If I Ran the Zoo were seriously concerned that the image of the Yerka tribesmen has the potential to perpetuate racism, then why take the initiative away from parents? Why not simply plaster a warning label on the books, and encourage parents to use little Gerald McGrew and his funny creatures as a teaching tool? (Of course, this might rob the image of its comic potential, too.) The publishers are clearly engaging in overkill, but that sort of fanaticism is a characteristic of cancel culture. The publishers themselves may simply be seeking some progressive “cred,” but the “panels of experts” are more likely a different breed, fanatics engaged in a struggle to replace an older ruling elite whose traditional moral code has for some time been eroding.

As the great sociologist Philip Rieff argued, no culture has ever “escaped the tension between…control and release”—the term “release” referring to techniques of remission from the dominant system of moral demands. If that tension wholly collapses, no culture worthy of the name can be sustained until a new system of demands replaces the old. Prior to that, as the old system loses its hold, “massive regressions occur” in which large swathes of the population revert to levels of emotional and physical violence unknown in the modern West. To avert social catastrophe, new elites compete for dominance. Today, it appears that the new elite most likely to establish dominance is doing so by the instigation and manipulation of conflict over racial and gender identity.

Under such circumstances, it may seem trivial to take a stand with little Gerald McGrew, but cancel culture must be fought, not with the tools of the enemy, but with, among other things, the power of laughter and the imagination.

Image Credit:

A copy of the Dr. Seuss book If I Ran The Zoo seen on a spinner rack inside Strand Book Store in New York, NY, March 2, 2021. It is one of six books which will no longer be published due to alleged hurtful representation of certain people and cultures. (Sipa USA / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply