Greek Diary III by Thomas Fleming • February 8, 2010 • Printer-friendly

We had a big but quite mediocre lunch near the Agora, at Attalos, and by the time we got to the entrance, we found out they had changed the schedule for visiting the Agora. Returning the next day, we took our time getting lost on the site, which is impossible not to do, even with the straightforward guidebook put out by the American School. Still, each time I visit it seems to make more sense, and this time I point out the shop of Simon the Cobbler where Socrates is supposed to have instructed young men who were not old enough to enter the marketplace.

On a little eminence overlooking the Agora stands one of the best-preserved temples in Greece: the so-called Theseion, which is almost certainly the Temple of Hephaestus. Despite the crowded morning schedule, we still find time to fit in the Kerameikos cemetery in which so many beautiful funeral monuments were erected.

For Greeks who were not initiated into a mystery cult, death was the end of everything worth having or experiencing. The shadowy life of the souls in the realm of Hades was nothing to look forward to. While later Greeks imagined Achilles spending a blissful eternity in the Isles of the Blessed, Homer tells another story. In the Underworld Achilles tells Odysseus—who is just there on a visit—that it is better to be a poor man’s slave than king in the land of the dead. Nonetheless, the Athenians were neither fatalists nor hedonists, but men and women who tried to do their ordinary duties every day. What immortality they expected was the remembrance and reverence they received from their living relatives, hence the touching portraits of dead spouses and children. I cut my sermon short to leave a little time for lunch. Some of us head to “To Kapheneio,” one of the best places in the Plaka.

The term Greek cuisine, as the Chief keeps on insisting, sometimes seems oxymoronic. In cities and tourist shrines, restaurants and tavernas are predictably mediocre and often quite bad. I have been to Delphi and Olympia twice and put up with the usual taverna food—Tzatziki, bland kephtedes, overdone souvlaki. One of the better places in Delphi is Bakkhos, but I was astonished by the rotten food our group was given on this trip. A tasteless salad, stale frozen and microwaved spanakopita that gave off an “eat at your own risk” aroma. Mercifully, I have blocked out the rest except for the very bad wine. The fact that it was stored in plastic 2 liter softdrink bottles did not bother me—there is a lot of drinkable wine found in such bottles, but this was atrocious stuff.

Taverna food, even at its best, can be as monotonous as Greek restaurants in the US—and that is saying a great deal. In the Plaka, for example, you can count on predictable food of a quality well below average. Guidebooks are rarely much help. Either they tell you about restaurants that are difficult to get to or they are simply repeating what a decade of previous writers have said.

Fish is very expensive in Greece, and while most decent restaurants now indicate which fish and shellfish are frozen, one had best beware. A good place will invite you to look at the fish and pick one out. On our last group trip we, Chris Check, and the Polins were in Nauplion/Nafplio, where we stumbled into a nice fish restaurant near the water. It turned out to be Savouras, probably the best fish place in town. The Flemings, after the group broke up, drove to Nauplion and returned to Savouras, which was as good as we remembered. The waiter or maitre d’ was very smooth and helpful, and our grilled Dorato was excellent. In the end he comped us a dessert and some tsipouro, the Greek version of grappa. Served cold and strong tsipouro or raki is a perfect way to end an evening: Sometimes, the end proves to be a crashing halt. (Note to Ship and Jimmer: What you are calling jetlag is more likely to be either tsipouro deprivation or liver damage.)

Over the past dozen years, I have had to find hotels and restaurants, both at home and abroad, for groups. I used to do it all by myself. It is not an easy task, especially if you are not terribly familiar with the town or with the local cuisine. Most people fall back on guidebooks, but this can be a serious mistake. If a restaurant has been in Fodor’s or Frommer’s for a few years, it has probably turned into a complete tourist trap. The big exception are very traditional, well-established, and usually expensive restaurants. When a little neighborhood joint gets discovered, the proprietors cannot resist the temptation to sell out. We used to go, year after year, to the Taverna Romana in Rome, not far from the Forum Romanum. The owners were fairly unpleasant and the place was a complete dump, but their rustic sausage and cheese were wonderful, and their traditional Roman cuisine was better than in more expensive restaurants. Then came the day when a Chinese tour group marched up. The rest, as they say, is indigestion. On the other hand, Dar Pallaro, the very famous prezzo fisso family joint near the Campo dei Fiori–it has been in and out of guidebooks–has not changed a bit. If you know anything about food, trust your nose long before you trust the written word, including mine.

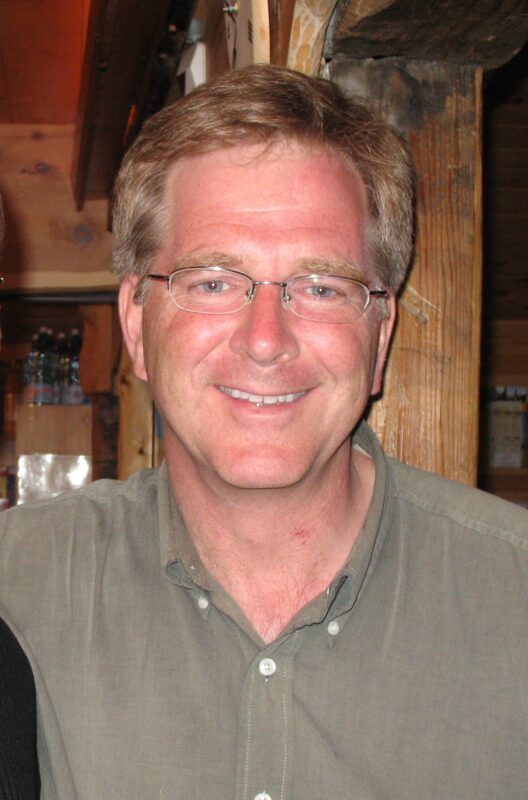

Back to Athens and Greek restaurants. The worst guidebooks, generally, are the Rick Steves series. Steves, who combines Mark Twain’s contempt for civilization with Ned Flanders’ naiveté, is at his worst in Greece. In a section devoted to the Peloponnese, he does not so much as mention Mistras and warns, with his peculiar brand of American puerility, that more than an hour at Mycenae would be tedious: “I’m Myceaneed out.” The way he dresses–part Safari part beach–is enough to bring a smirk to any middle class European. Just about anything he tells you to do, do the opposite. Yet, his researchers have done an above average job on restaurants, beginning with the good advice to avoid places with bilingual menus in the window. I am citing now from memory, but his recommendation of “Thespis” as a taverna reminiscent of the good old days is spot on.

I remembered the place, which a friend had taken me to six years ago, and Chris Check remembered roughly where it was. The street (Thespidos) was empty and when the proprietor spotted 8 people, he came rushing out promising the culinary equivalent of the moon. He assured us he could do ouzo and mezedes in a hurry, which he did. It was warm enough to sit outside and enjoy a magnificent view. The “homemade” ouzo, he gave to us; the barrel wine was more than drinkable; and the food was actually quite good, excellent tiropides (cheese pastries) and marinated anchovies and more than passable Tzatziki, kephtedes, and the “savory” pork stew with onions and red bell peppers they are so fond of. The bill for, I believe, nine of us was 100 Euros.

I remembered the place, which a friend had taken me to six years ago, and Chris Check remembered roughly where it was. The street (Thespidos) was empty and when the proprietor spotted 8 people, he came rushing out promising the culinary equivalent of the moon. He assured us he could do ouzo and mezedes in a hurry, which he did. It was warm enough to sit outside and enjoy a magnificent view. The “homemade” ouzo, he gave to us; the barrel wine was more than drinkable; and the food was actually quite good, excellent tiropides (cheese pastries) and marinated anchovies and more than passable Tzatziki, kephtedes, and the “savory” pork stew with onions and red bell peppers they are so fond of. The bill for, I believe, nine of us was 100 Euros.

If I am correctly recalling it, Steves also recommends the universal favorite, “Scholarcheio,” the oldest restaurant in the Plaka. Until this past summer, I stayed away, fearing a tourist trap, but now, having eaten there four times, I can say it is still quite a bargain—14 Euros per person, including wine, for more food than you can possibly eat. It is absurdly charming but not phony, and, though during the summer they are packed with tourists, in the off-season we found almost as many Greeks as visitors, though not many of either. They handled our group dinner as well as they would have treated a couple, proving it is possible to do this sort of food correctly.

Catty-corner from “Scholarcheio” is a somewhat more upscale mezedes place, “To Kapheneio” (the coffee shop), where we have lunch twice. The Chief liked this place the best, particularly the pork with prunes I ordered and a braised beef with sweet spices (allspice and cinnamon). The fried kephtedes were particularly good, and the house wines were excellent, especially the very spicy Malvasia. While the price of the individual “small plates” is higher than elsewhere, the total bill is not anything to complain about. One is more quickly satisfied by very savory dishes.

We had planned on going back to Attikos, overlooking the Acropolis, where we ate twice last summer, but it was closed the night we wanted to go there, and we ended up at a snug little place with a fire, Taverna Theklas, which had a few unusual dishes and good food overall. We had eaten there in 2004, with Chris Check and the Polins, and liked it. The waitress’s poor English gave me an occasion to try out my slightly less poor Greek. We would gladly have gone back, but Theklas was closed. Previously, I would have said that Mani Mani was one of the best places in Athens, at least in the neighborhood of our hotel (on Falírou), and we ate there twice this time. Nothing was bad, and the bottled wine was quite good. The quail was delicious, but many dishes suffered from a less than competent kitchen staff, whom they unwisely allow the patrons to observe. The Chief, who was unimpressed, said he would fire people if they worked so sloppily for him.

Our one real discovery we owe to Kellen and Fleta Buckles, stout comrades at many a Summer School and at the last Winter School we held in Rome. When they told me what a good time they had at an untouristic place a stone’s throw from the hotel, I felt they were being naïve. I knew the location, a rather dingy kaphaneio, which until a few months ago was a hangout for older Greek men drinking and smoking. The new bright colors, I imagined, were simply a sign they were selling juice and overpriced pre-prepared food to attract the visitors to the Museum. But, striking out at the places I knew, I decided to risk it.

As soon as we sat down, Giannis the proprietor told us not to expect a touristic restaurant. If we wished to eat, we would have to accept their somewhat primitive accommodations and style, meaning we were still free to leave. He was friendly and sent his young wife, Katerina, over to take our order. The menu was a bewildering array of fish, including “snales,” which they were out of. I decided to test the place by asking her to order for us. While we got much too much food, she went all out.

The first dish, dakos, is a traditional Cretan variation of crostini, made with slightly toasted barley rusks. The Chief immediately complains about the poor quality, mistaking the barley rusk for stale bread. Then the hot beetroot plus greens arrives, just lightly flavored with vinegar (“from my town in Crete”). Now, I like beets well enough and really enjoy Patzaria—beet greens, which are often thrown away by grocers—and we serve both at home, but these were much better. Things were looking up. Then came “minnows ” fried in a pan, a fried whole fish, wonderful fried whole shrimps, all washed down by very cheap but drinkable wine. We ended up spending about 20 Euros per person, but then each of us ate for two or three people. We simply could not help ourselves.

Day after day we return in groups of shifting composition, for lunch or dinner or just for drinks. One afternoon we come a bit early, 12:45, and Katherina promises us we’ll be fed as soon as the fishes arrive from the dragnet. Finally, a van pulls up, and she cries out with joy, “the fishes are here, the fishes are here.” It is worth the wait and worth the excitement. We eat until we can eat no more. My wife and most of the others rush off for her tour of the Acropolis Museum, but some of us stay to finish the food and wine. Just as I am about to pay, Katherina tells us that today she has the “snales” advertised on the menu. Thirty minutes later, they arrive, tasting of vinegar and rosemary and somewhat chewy. After the first dozen, I realize that the chewiness is part of the experience. By now, after several fish, fried shrimps, a mussel stew, and fried potatoes—to name only a few things—I cannot eat another snail and I bring them to other tables to share with us. I ask Katherina how she prepared them: “You have to bury their faces in salt, otherwise they will crawl up into the shell and you will not be able to get them out.” The chief wonders if his customers in Maine are ready for live snails cooked Cretan style.

Giannis is a devotee of Greek music, and the walls of Aphrodite are covered with pictures of famous musicians, whose music he plays on the stereo. I ask him where there is good music in Athens. He sighs. “Athens is not Greece. Athens . . . ” and here he pretends to spit. “Go out into the country and you will hear the best music.” One evening, when I am not present, a few musicians show up and start to play. The next night I see friends in the place and stop in for a glass of wine. Before long I am at the bar listening to Giannis talk politics. We share, it seems, a similar outlook, and he is proud to be an official member of a party many of whose leaders I have met. After 5 shots of homemade raki he insists on pouring out at his expense, I promise to bring him an interview with me on the subject of Kosovo just published in Patria.

When we go in for lunch on our last day, Giannis leaves and returns with presents for Fr. Barbour and me. We exchange phone numbers, though I cannot imagine the proprietor of a small place finding time to go down to Nafplio, where we will be spending the next week. On the other hand, I assure him, I shall certainly be back within a year and probably next summer.

At first I was reluctant to spread the news of this treasure, but then I realized that readers of the Chronicles website are not so numerous as to crowd me out, even if half of them visit Greece in the coming year. If you do have a chance to go, remind them of the bearded “professor” and his friends.

Tagged as: Greece abc123″>7 Responses<a href="#respond"

Leave a Reply