Mark Twain, America’s Greatest 19th-century writer, never had anything nice to say about anyone in public office, for he had a great aversion to politics and politicians, often using his clever wit and keen intellect to rip them to shreds in public addresses and in his voluminous writings. To uproarious laughter from a Republican audience in 1876, Twain noted that “we serenely fill great numbers of our minor public offices with ignoramuses; we put the vast business of a Custom-house in the hands of a flathead who does not know a bill of lading from a transit of Venus, never having heard of either of them before.” He once likened members of Congress to fleas and even described Judas Iscariot as a nothing more than a “low, mean, premature, Congressman.”

But Grover Cleveland was different. He was, Twain wrote to his daughter, “a most noble public servant—and in that capacity he has been utterly without blemish. Of all our public men of today he stands first in my reverence & admiration, and the next one stands two hundred twenty-fifth. He is the only statesman we have, now. Cleveland drunk is a more valuable asset to this country than the whole batch of the rest of our public men sober. He is high-minded; all his impulses are great and pure and fine. I wish we had another of this sort.”

To Cleveland, Twain wrote, “Your patriotic virtues have won for you the homage of half the nation and the enmity of the other half. This places your character upon a summit as high as Washington’s. … When the votes are all in a public man’s favor the verdict is against him. It is sand, and history will wash it away. But the verdict for you is rock, and will stand.”

Who was this man who had so captured the attention of Mark Twain? He was born Stephen Grover Cleveland on March 18, 1837 in New Jersey. After gaining a law degree and beginning a legal career, in the early 1870s, he began his public life, holding four elected offices during his lifetime, all executive positions—sheriff of Erie County, mayor of Buffalo, governor of New York, and president of the United States. In all of his offices, from the first day to the last, he steadfastly followed the principles of

Jeffersonian conservatism, so much so that he has been called the “last Jeffersonian,” a “forgotten conservative,” the “last good Democrat,” “the last libertarian president,” and “the last small-government candidate the Democrats would ever run” for the presidency.

Cleveland had great admiration for the founder of the movement, Thomas Jefferson. “The memory of Jefferson’s patriotism, conservatism, wisdom, and devotion to everything American should be kept warm in the hearts and minds of his countrymen, and especially of his political followers. The contemplation of these things should serve to check every tendency to follow false and delusive lights, and to tread untried and unsafe paths,” he said. On another occasion he wrote, “It is well in these latter days to often turn back and read of the faith which the founders of our party had in the people—how exactly they approached their needs and with what lofty aims and purposes they sought the public good.”

Cleveland’s public career covered a host of issues that are still relevant today: public character and behavior of our candidates, the role of government in the everyday lives of the people, the burden of taxation, the distribution of wealth, government involvement in an economic depression, monetary policy, and complex foreign affairs.

One of the most well-known aspects of his executive career was his nearly-obsessive safeguarding of the public treasury, even in times of economic depression, using “his sledgehammer veto.” Every single spending bill was heavily scrutinized and he rejected every unconstitutional raid on the treasury. “Economy in public expenditure,” he repeatedly reminded Congress, “is a duty that can not innocently be neglected by those entrusted with the control of money drawn from the people for public uses.” In his two terms in the White House, Cleveland vetoed 584 bills, the most by any president until Franklin Roosevelt.

Perhaps his most well-known veto came during his first term when a severe drought struck Texas. In February 1887, Congress passed a bill known as the “Texas Seed Bill,” an appropriation of $10,000 to purchase seed for Texas farmers. But Cleveland, in an act no modern president would dare to do, vetoed the bill, returning it to Congress with one of his most famous declarations:

I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution, and I do not believe that the power and duty of the General Government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit. A prevalent tendency to disregard the limited mission of this power and duty should, I think, be steadfastly resisted, to the end that the lesson should be constantly enforced that though the people support the Government the Government should not support the people.

The friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied upon to relieve their fellow-citizens in misfortune. This has been repeatedly and quite lately demonstrated. Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the Government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.

But Jeffersonians everywhere, even in Texas, praised Cleveland’s veto, and people across the country donated money in excess of $100,000 for those hurting in Texas, which was more than 10 times what Congress had planned to spend.

Another controversial veto was the Dependent Pension Bill, which Cleveland rejected in 1887. Seeking to reward a favored constituency, Union veterans, the Republican Party expanded the program of pensions to the point that it essentially became a national welfare system. Even The New York Times referred to it as the “pauper pension bill.” Cleveland, unhappy with the diminished standards, summarily vetoed the bill as a raid on the treasury, stating that the pension list would cease to be “a roll of honor” but would include those “willing to be objects of simple charity.” He endured the wrath of Union veterans but did what he believed to be the right and honorable thing by vetoing the bill.

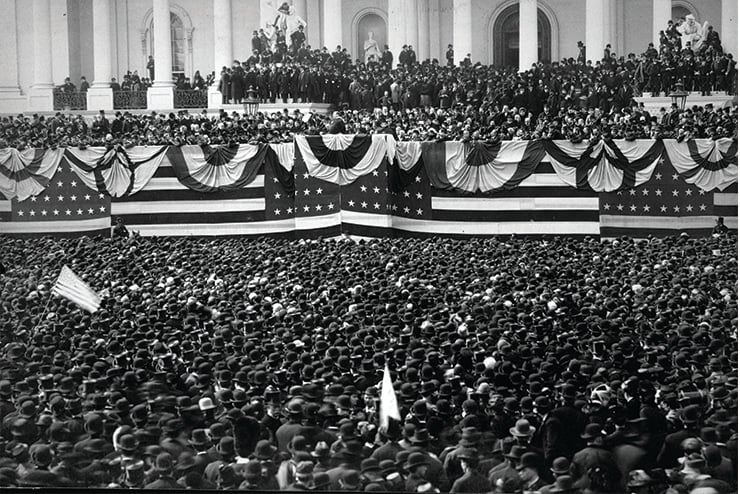

(John F. Jarvis / U.S. Library of Congress)

During his second term, in 1896, as the economy was recovering from the Panic of 1893, President Cleveland refused congressional calls to actively intervene to stimulate a very depressed economy. One plan was to inject hundreds of millions of dollars of new currency into the economy by funding public works projects, a forerunner to the New Deal. Cleveland said no, as did the Democratic Congress.

But after a Republican takeover in 1894, Congress sent Cleveland a bill for river and harbor construction, which was essentially a Keynesian-style stimulus full of earmarks. Coming to the end of his final term, Cleveland was still not having it. “There are 417 items of appropriation contained in this bill and every part of the country is represented in the distribution of its favors,” he noted in his veto message. “In view of the obligation imposed upon me by the Constitution, it seems to me quite clear that I only discharge a duty to our people when I interpose my disapproval of the legislation proposed. Many of the objects for which it appropriates public money are not related to the public welfare, and many of them are palpably for the benefit of limited localities or in aid of individual interests.” If he were to sign such a spending bill, it would be a violation of constitutional principles. “Economy and the exaction of clear justification for the appropriation of public moneys by the servants of the people are not only virtues, but solemn obligations.” Throughout his career, Grover Cleveland never betrayed the American taxpayer.

In the realm of foreign affairs, Cleveland maintained the Jeffersonian policy of nonintervention, especially in his second term. He strove to restore the Hawaiian monarchy to its rightful place in society, after an American-involved coup had displaced the Queen, yet was ultimately unable to do so, and successfully arbitrated a border dispute in Venezuela, keeping the British from expanding their reach in the Western Hemisphere. But one of the biggest issues confronting the United States was Cuba, where a revolt broke out in 1895. Imperialist members of Congress were eager to push the president into war. Cleveland likened their attitude to an “epidemic of insanity.” But he did not budge from his position of nonintervention. Jingoistic Republicans in Congress then threatened to declare war on Cuba without him. To that Cleveland replied, “There shall be no war with Spain over Cuba as long as I am president.” If Congress declared war, he would not, as commander-in-chief, mobilize the army. Instead he signed two neutrality proclamations in regards to Cuba. And that ended the debate, though America eventually went to war in Cuba under Cleveland’s successor, Republican William McKinley.

Cleveland retired from public office after rejecting pleas by Jeffersonians to seek a third term in the White House in 1896. Instead, the party nomination when to William Jennings Bryan, a populist from Nebraska, thus moving the party to the left and infecting both national parties with progressivism. This development caused Cleveland to become very pessimistic over the future direction for his beloved Democratic Party, for Bryan advocated more taxation, more spending, inflationary currency, and more government intervention in the lives of the people. Making matters worse, in three of the next four presidential contests, the party nominated Bryan to head the ticket.

Cleveland and Bryan represented separate wings of the party, which became an open breach that kept Democrats from power for 16 years. The split was so pronounced that Cleveland and Bryan remained in a virtual political war for years. Distrustful of Bryan, Cleveland believed that he “has not even the remotest notion of the principles of Democracy.”

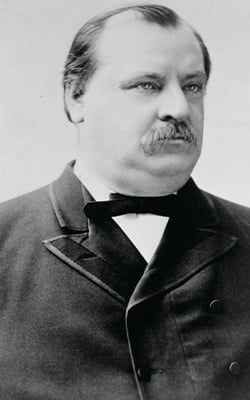

circa 1873. (C. M. Bell / U.S. Library

of Congress)

In his retirement, Cleveland returned to the state of his birth, New Jersey, where he served on the Board of Trustees for Princeton, and got into a few squabbles with the university’s president, Woodrow Wilson. Cleveland was not active in party business but remained concerned, nonetheless. Until the end of his life, he wrote letters to friends hoping to defeat what he called “Bryanism,” ideals he considered a “disastrous heresy.” If the old Jeffersonian principles perished, then no party would be advocating for the ideals of the revolution and America would be lost. In 1899, he wrote his friend, and former cabinet member, Richard Olney. “And the poor old Democratic party! What a spectacle it presents as a tender to Bryanism and nonsense!”

The party had but one opportunity to regain the presidency in 1900, Cleveland believed, but only if Bryan and his followers were expunged. “The Democratic party, if it was only in tolerable condition, could win an easy victory next year; but I am afraid it will never be in winning condition until we have had a regular knock-down fight among ourselves, and succeeded in putting the organization in Democratic hands and reviving Democratic principles in our platform.” If that fight did not come, the people would be faced with the same candidates that were on the ballot four years before. “Bryanism and McKinleyism! What a choice for a patriotic American!” he wrote.

The situation was so bad that Jeffersonians within the party tried to get Cleveland to come out of retirement and run for a third term in 1908 but he passed away in June of that year. A few days later, Mark Twain wrote to the former First Lady, Francis Cleveland, of her deceased husband. “He was a man I knew, loved and honored for twenty-five years. I mourn for you.”

Indeed, so too did the country. With the death of Grover Cleveland, the old Jeffersonian Democratic Party died as well. In 1909, an old Cleveland Democrat wrote, “[the] Democratic party, as we knew it, is dead.”

Leave a Reply