If California were to secede from the United States and establish itself, as its first Anglo settlers once intended, as an independent republic, it would instantly emerge as one of the world’s richest nations. As it is, one in every ten Americans now resides in the so-called Golden State. Its economy affects not only those of neighboring states but those of whole nations—Mexico, Canada, Singapore, even Japan. It is somehow different in just about every way from the rest of the country. To live in California is, as Aldous Huxley observed, to be forever part of a separate reality.

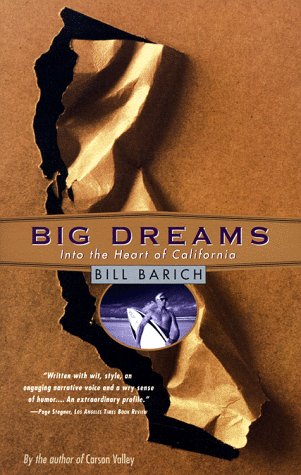

Bill Barich, a journalist, undertakes to provide a portrait of his state in his fine and aptly titled book Big Dreams. His method is to travel from Point A to Point B and to narrate all that he sees, a common enough literary device that is nevertheless challenged by California’s vastness. Realizing the complexity of his mission, Barich offers us a beeline ramble through the state, beginning in the high desert east of Mount Shasta and wandering leisurely through the Klamath River Valley, Crescent City and Hoopa, the Tuscan landscapes of the Anderson Valley and the Monterey Peninsula, down to Death Valley and the dusty shores of the Salton Sea. The author’s appreciation of the subtleties that separate one place from the next yield a lucid, entertaining travelogue.

With his command of California history, Barich sees continuities that other writers have sometimes overlooked. Orange County country-clubbers may curl their lips in revulsion at the mention of libertine San Francisco—a cultural antipathy from which Ronald Reagan made much political hay—since San Francisco has long been “willing to take in every misfit Californian, as well as misfits from elsewhere—the wounded, the defrocked, the intellectually adventurous, and the sexually prurient—and it bound them together into a community that managed to work. That was its genius and its salvation.” It remains so today.

Barich has a gift for painting large word pictures, framing whole cities and bioregions in the space of a paragraph or two. The sweep of his vision causes him to trip on occasional facts; his account of the origin of Boontling, an impenetrable Mendocino County argot, is false, as are many of his place-name etymologies. Still, he conjures up descriptions that linger in the mind, as when he limns Los Angeles as “the world’s first post-apocalyptic, postmodern, postliterate city, a place without absolute boundaries that floated freely beyond the grasp of history, parody, and any concerns other than the momentary.”

His ferreting out of oddments and ironies that alternately reinforce and destroy California stereotypes makes Barich’s book especially entertaining. The official corporate biographers of both men, for instance, will not be pleased by his observation that Walt Disney and Ray Kroc (the founder of McDonald’s) served together in an ambulance unit in Wodd War I, where Kroc spent his leisure time in French restaurants and brothels while Disney carefully manufactured fake German helmets, complete with bullet holes and chicken blood. Disney’s arts of deception would soon alter the very landscape of California, though Kroc seems to have left his knowledge of haute cuisine somewhere on the Western Front.

Barich wryly notes that despite a half-century of anti-Chinese (and later anti-Japanese) activism on the part of its Anglo overseers, California has long benefited in every way from its Asian ties, to say nothing of its Asian-American citizens. He takes little joy in pointing out one of the state’s few current growth industries in a recession-mired economy when he notes that “only the prisons were as overcrowded as the public schools,” and he warns that illegal immigration threatens to destroy an already strained network of social services.

Barich closes Big Dreams on a strangely optimistic note, given all that he has seen and recorded and his knowledge that the population of California can only grow while its resources wane. (Perhaps he has not heard, too, that Charles Manson’s followers are more numerous today than they were in 1969.) Even a clear-eyed journalist, I suppose, has somewhere to indulge in fond speculation; and California has always been, and may always be, the place where Americans go to test their fantasies—and the weirder, the bigger, the better.

[Big Dreams: Into the Heart of California, by Bill Barich (New York: Pantheon) 546 pp., $24.00]

Leave a Reply