So many things have been said in praise of McCarthy’s work that it is hard not to sound like an echo. Inevitably, the reviewer notes the energy and grace of his style, and there is no gainsaying that. The relentless power of his sentences and the tautness of the action can leave a reader emotionally exhausted. After reading The Crossing some time ago, I dropped back and read Blood Meridian, which I had missed somehow; afterward I told my wife that I was going to have to let this wildcat go for a while. I was simply drained from following his spoor in such wild terrain and in such weather.

Earlier appraisals of McCarthy’s work have often lacked any recognition of its humor, whether of situation or of dialogue. In The Crossing, the laconic exchanges between Billy Parham, the central character, and his brother Boyd, or between some of the older men, are vintage American Rural. An example of this occurs early in the novel in a conversation between Billy and an old man driving a Model A pickup. Billy has been out setting traps for a female wolf, but doesn’t particularly want to say so to the old man who has stopped him in the road. Billy instead remarks that he has seen a lot of coyote sign. The old man: “I aint surprised. They done everthing down at our place but come in and set at the table.” Then the old man whips out a big lighter and in the big flame lights his cigarette.

I had to quit using the hightest, he said.

Yessir.

You married?

No sir. I aint but sixteen.

Dont get married. Women are crazy.

Yessir.

You’ll think you’ve found one that aint but guess what?

What.

She will be too.

Before they part, the old man tells a tale about the New Mexico mountain lion talking to the Texas mountain lion, a fine example of Southwestern yarnspinning. The Texas lion was gaunt and starving. When he explained he had been hunting Texans in the traditional way, screaming and then jumping on them, the New Mexico lion said, “it’s a wonder you aint dead. Said that’s all wrong for your Texans and I dont see how you got through the winter atall. Said look here. First of all when you holler thataway it scares the sh-t out of em. Then when you jump on top of em thataway it knocks the wind out of em. Hell, son. You aint got nothin left but buckles and boots.”

Such tough, high laughter serves only to heighten the more serious sections of the story. For The Crossing is a fully realized Bildungsroman, a story of passage. The “crossing” first denotes Billy’s crossing the Texas-Mexican border and entering another country. He must often speak a language other than his own, for he is leaving the known domain and passing to a new, unknown one. At the same time, he is crossing into manhood. Though only 16 he already has many skills, not having been reared in a pampered suburb of the American 90’s, but in the rural southwest of the 20’s and 30’s, Hidalgo County, New Mexico. The novel reminded me that my relative, Jesse James, was only 14 or 15 at the beginning of the War Between the States. Like Billy Parham, he developed skills of survival, of horsemanship and of arms, in his teens.

Appropriately, during this passage from innocence to experience, Billy has many teachers. Early in the story, his father teaches him to trap wolves, to conserve his horse’s strength in deep snow, while his mother instructs him to keep the Sabbath and to offer thanks for their food. In the bravura performance of Part I, in which Billy learns to catch the wolf and then returns it to its home in the Mexican mountains, he seeks the ancient knowledge of trapping from an old man, Don Arnulfo. Don Arnulfo is one of the numerous sages the boy listens to throughout the narrative. Billy asks him about a wolf scent. Number Seven Matrix, that he has obtained and receives instruction not only about wolves but about the matrix of the world, upon which he is invited to meditate. “He said that the matrix was not so easily defined. Each hunter must have his own formula.” Further, “El lobo es una cosa incognoscible.”

Billy Parham’s journeys are filled with signs of the world that he must interpret in order to live. He must weigh the different words, the different perspectives of the sages, whether of Don Arnulfo, the church caretaker, the blind man, the prima donna, or the gypsy. He is confronted with what every human being confronts: how to separate appearance from reality. He is instructed by the blind man that the visible world is a distraction, that one must listen: that the world hides more than it reveals. In a moving scene (reminiscent of Stephen Dedalus’s epiphany at seeing the girl wading in the water), Billy watches the prima donna bathing naked in the river: “He saw that the world which had always been before him everywhere had been veiled from his sight. Nothing would ever be the same.” Counterposed to this is the observation by the prima donna’s co-worker that only the mask is real. She adds, “Perhaps it is true that nothing is hidden. Yet many do not wish to see what lies before them in plain sight. You will see.”

Riding through the wilderness of signs, this vaquero-knight encounters evil, always realized in believable villains: the horse thieves, those who took the wolf, those who stabbed his horse. Like any knight, he protects women and the weak, and tries not to lie. The poor are the quickest to recognize him for what he is and together they share and take their food as sacrament, the tortilla “the great secular host of the Mexicans.” A part of his chivalric Quest is the return of his father’s horse and the return of his brother’s body. Throughout this story, the protagonist and his sage-teachers meditate on evil and justice. Thoughts and words about God saturate the entire novel. Perhaps The Crossing is above all a theodicy, or at the very least, a theodic investigation. I have not come upon any such endeavor of this magnitude in recent fiction.

McCarthy has an immense capacity for what Keats described as negative capability. Like Hamlet turning a skull in his hand, McCarthy turns the world of The Crossing this way, now that, asking us to consider the matter with him. His book is not a religious tract. During a time when one begins to despair about fiction being reduced to political statements by one victim group or another, it is gratifying to come upon the real thing.

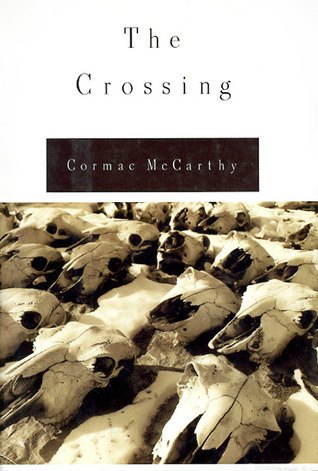

[The Crossing, by Cormac McCarthy (New York: Knopf) 426 pp., $23.00]

Leave a Reply