One of the casualties of the current culture wars is the Western. No other genre, it seems, is so politically incorrect. The Western is accused of racism, sexism, and imperialism—three strikes and you’re out. These charges receive sophisticated expression in Jane Tompkins’ West of Everything, published under the prestigious imprint of Oxford University Press. According to its thesis, “The Western doesn’t have anything to do with the West as such. It isn’t about the encounter between civilization and the frontier. It is about men’s fear of losing their mastery, and hence their identity, both of which the Western tirelessly reinvents.” The cowboy astride a horse exemplifies an “ethos of dominance.” This horse-rider relationship is a “politics,” and each appearance of a horseman on the horizon “celebrates” male hegemony. (I suppose we are to assume that if men hadn’t had such an overweening desire for political power, they might have found another means to traverse those large distances in the West.) Cattle as well as women are political victims: according to Tompkins, the John Wayne cattle-drive film Red River is really a film about enslavement and massacre—of cattle. The filming technique, she suggests, helps disguise this fact by only showing the cows from the side so we can’t look into their anguished faces and sympathize with their political plight.

Tompkins stretches the motto “everything is political” to the limits. She views even landscape as politics: “The harshness of the Western landscape [which she seems to reduce to John Ford’s panoramic shots of Monument Valley] is so rhetorically persuasive that an entire code of values [racist, sexist, patriarchal] is in place, rock solid, from the outset, without anyone’s ever saying a word.” I wonder what a Navajo woman would make of this astonishing assertion that the landscape of the Southwest is sexually and racially oppressive. Or what response would we expect from an ecofeminist who views nature (including desert) as a woman victimized?

Besides seeing politics lurking behind every cactus, Tompkins is reductive in another way. She treats novels and films as a single entity, asserting that “when you read a Western novel or watch a Western movie on television, you are in the same world no matter what the medium: the hero is the same, the story line is the same, the setting, the values, the actions are the same.” This is generalization from limited sampling. The commercial exploitation of familiar formulas notwithstanding, the Western genre taken as a whole displays much variety in content and quality. And furthermore, novels and films are too different to be lumped together. One has the uncomfortable feeling that Tompkins’ research consisted largely of renting a stack of videos from her local Blockbusters. This would explain her remarkable claim that there are no Indians in Westerns. What she really means is that the main Indian roles in a certain group of Western films were played by white actors—Jeff Chandler as an Apache, for example. Totally ignored are the many Western novels that explore the Indian perspective perceptively and sympathetically. To lump together the wide range of Western novels—differing so much in quality of writing, historical research, and imaginative vision—with products of Hollywood’s film system is unfair and misleading.

Richard S. Wheeler’s fiction provides a counterexample to such generalized and reductive characterizations of the Western. Wheeler began writing Westerns in the mid-1970’s, at first for money, but then with an increasing desire to tell more realistic and historically accurate stories than the usual Western provides. (See his essay “Writing Offbeat Westerns” in the August 1991 issue of Chronicles.) He was interested in character more than plot, and in characters with ordinary strengths and weaknesses rather than in mythic heroes and unalloyed villains. He wanted to widen the appeal of Westerns to attract a more educated and literate readership, including women. This meant upgrading the vocabulary, using figurative language more extensively and skillfully, widening the range of characters (male and female), and getting deeper inside their minds than the usual action-adventure allows. It also meant treating aspects of the Western frontier largely ignored in the familiar formulas associated with the cattle kingdom.

He was repelled by the anomie of recent Western films and television shows with their cynical violence and amoral nightmare atmosphere. “These malignant stories,” he says, “drained away the complex, warm social relationships that occur in real life. The tender emotions vanished—love, loyalty, mercy, laughter.” Believing that such dark views along with the narrow parameters of the commonplace Western have distorted or extinguished the public’s interest in the frontier, he has endeavored to write stories with characters who have values and beliefs, who are connected with others, who can laugh and cry, who can shape their lives with dreams and effort. He sets them within moral frameworks and restores what he sees as “the traditional virtues, honesty, bravery, courage, loyalty, warmth and sunniness” that people once treasured in fiction. He suspects that much recent “literary” fiction has abandoned this traditional ground and that entertainment novelists are appropriating it. He has certainly staked out his claim. But in doing so he is writing against the commercial grain. The readership of mythic Westerns seems stable (witness the popularity of Louis L’Amour), and publishers do not want to experiment. Fortunately, he has found publishers for his approach, but it has not been easy. His is a conservative endeavor: Wheeler is firmly convinced that the best values and traditions of the American frontier, which are being distorted by commercial exploitation and myopic revisionist attacks, are worth conserving.

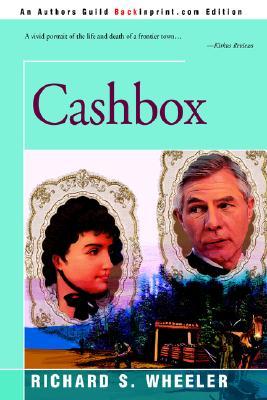

Cashbox is the culmination so far of what Wheeler is aiming at. It is the story of a Montana silver-mining town that blossoms and withers between 1888 and 1893. The town is modeled on the actual mining town of Castle, and the novel reflects a good deal of historical research. The descriptions of mining technology, frontier journalism, labor relations, silver politics, and the social makeup and activities of such a town are informative and bear the stamp of authenticity. It is the story of a community rather than of a single protagonist. The cast of characters, men and women, is large and varied. The chapters alternate in their focus on individuals, and these lives are skillfully blended into a vivid and at times moving portrait of that unique social phenomenon, the evanescent frontier boom town. Unlike the characters of formula Westerns, the people of Cashbox combine virtues and faults, ideals and frailties, and they change and grow. There is no mythic hero or stage-property heroine, no chasing and shooting, no town taming, no feuding or vengeance, and no final walkdown. There is plenty of love interest, but it isn’t young love or simply physical love. It is middle-aged love, domestic interactions, tender relationships besides those of physical sex—relationships in which men and women struggle to recognize and respect the broader needs and desires of each other.

The epigraph from Thoreau’s “Walking,” an essay that elaborates the symbolic implications of the West and westering, suggests Wheeler’s principal theme: the West as a place for dreams, tests of character, and experiments in human possibilities. If this symbolic West is a myth, it is a myth worth preserving. And popular fiction is not a bad place for preserving it, especially since current “literary” fiction often seems indifferent if not hostile to that task. A book that convincingly portrays the positive heritage of the Western frontier, and can be read by everyone, does much to hold our society together. As Joseph Conrad observed, “We are the creatures of our light literature much more than is generally suspected in a world which prides itself on being scientific and practical, and in possession of incontrovertible theories.” For those who value the influence of the frontier on the American character, it is fortunate that a writer as skillful as Wheeler is committed, despite adverse ideologies and unsympathetic publishing trends, to enlarging and revitalizing the Western genre.

[Cashbox, by Richard S. Wheeler (New York: Forge) 381pp., $23.95]

Leave a Reply