Larry Johnson’s first book of poems, Veins, promises an engagement with history and tradition that is respectful, lively, and current. Open to any page at random, and you will find examples of real language handled by a poet who obviously knows what a poetic line is. (So many contemporary poets do not.) Consider these wonderful lines taken completely out of context: “Or hunger hauls them glossing from the sea”; “Grass billows backward from the cliff[.]”

Many of these good lines bring history to life in good poems. One of the best, “Red Skeletons at Herculaneum,” is in the voice of a slave girl killed by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The poem ends “and the boiling sludge enveloped us with the sound / of vast black mothwings beating on the sun.” Such poems put one in mind of a well-made gumbo that combines layers of history, time-tested local ingredients, and attention to craft and process.

One can discover other such gems throughout, but, after reading the book cover to cover, I found that something about its overall structure strains the reader’s initial optimism. The book’s two sections are named Adrenalin Night and Adrenalin Light; the first section takes us on a journey from the present to 1821, thence from a.d. 406 to 966 b.c. This is done so programmatically that it obviously has some special meaning to the poet, but it serves no obvious function for the reader.

Almost every poem includes the name of a famous historical or literary figure in the title. We encounter Weldon Kees, James Wright, Ezra Pound, John Keats, Marcus Aurelius, Hadrian, Juvenal, etc. Unfortunately, this catalog of names and accompanying scenery, in descending order, starts to give the reader the sense of having stumbled into an apartment that is full of too many antiques, all of them arranged according to their time periods.

After 67 pages, we have a very clear sense of Johnson’s knowledge of, and keen interest in, the classical world and the lives of poets he admires. But is he trying to claim some poetic kinship with such figures by posing with them? Is there some issue of time and memory he’s playing with? Or do the 16 endnotes at the back of the book suggest something else? Erudition, maybe. The reader runs low on adrenalin, however, with 32 pages still to go in the second section.

Too often our tour guide engages in self-conscious jousting and posturing that become anachronistically ingratiating. The reader cringes when, in a poem called “Hangover in Memory of James Wright,” the poet says, “Your life wasn’t wasted. If anybody / reads and loves this poem / mine won’t be either.” This puts a huge burden on the poem—and the reader! On closer inspection, we begin to get the sense that when Johnson writes about a poet—say, Weldon Kees—he’s also trying to write like Kees: “Movies, green wormwood of all pianos lost?”; like Pound: “I turned a corner—a plaza, a pulsing crowd!”; like Lorca: “What you were is the thirst of an orange tree”; like Cavafy: “my eyes are as green as that Cretan stone.”

Such literary imitation takes real skill and can be a genuine tribute. But changing voices too often in series like this may also sound after a while like a fake British accent, giving a new spin to Yvor Winters’ “Fallacy of Imitative Form.” So, while the poems in which Johnson has done this are not uninteresting, and sometimes even very good, the problem here is that the reader can’t figure out who this guy is. Either we have a poet with impressive range, gifted at impersonations in a selfless way, or his antiques-filled apartment begins to feel also like a name-dropper’s wax museum.

Furthermore, what seemed pleasing at a glance about Johnson’s lines at times becomes disappointing in context with the embedding poem. Larry Johnson does have a good ear for blank verse, but his metrical variations tend to come too quickly, too close together across multiple lines, so that the iambic norm is lost. It’s as if he wants to work with a bouncy roiling rhythm where an occasional regular line provides relief. But just as the inner ear can’t take that on a curvy road, neither can the poetic inner ear take too much variation without regular relief. With more pattern, the odd trochee or anapest would have a much greater payoff value as a variation.

When we get to Adrenalin Light, the tone shifts entirely with much more free verse and personal poems about things like being in love with another man’s wife. On a wild dance floor, the speaker is thinking: “A spray / of saliva flits from your mouth to my upper lip, / I lick it, ecstatic—joy of the blood of stars . . . ” The reader cringes again, certain that he doesn’t know what voice or speaker he can trust here. Part of the problem could simply be the book’s structure; it is far too long, with too many different voices and tones that probably span much of the author’s poetic career, while simultaneously spanning as well so much human history in the poems. It’s possible that Johnson, who was born in 1945, tried to fit in a lifetime of his favorite poems and then struggled to find a rubric to organize them all. It’s his first book, but it wants to be a “New and Selected” one. Perhaps his editor is to blame for this, but the unfortunate consequence is that, in its weak moments, Veins, as a book, has too many veins trying to spread in too many directions. I suspect that the roux of Johnson’s gumbo was overcooked.

Despite these problems, once the reader is able to sift out the bathetic tonal shifts, the nice poems in the book do stand out. Probably the best one is “Moorish Idol,” written in rhyming couplets about a fish that’s revered superstitiously by Bengalese fishermen. There’s no funny accent here. The subject rings clearly through deftly handled syntax, meter, and rhyme.

Freed, the Idol streaks below to rills

Of coral searching for its mate. Its beak,

Scissorlike, snips the growth, rejects the freak

Intrusion of the breathless realms above—

It is pleasing and commendable, in our free verse-dominated age, that Johnson works in forms like the sonnet, blank verse, and the villanelle. Yet Johnson is often at his best in a free-verse “vein,” telling us about rural Mississippi and natural things. It gives us a clearer sense of who the speaker is. The poem “Once,” about a grandfather who shot an ivory-billed woodpecker because he wanted to show it to the speaker, is heartbreaking and speaks ages in one simple stroke about humanity’s place in history and nature, something that Johnson’s mystery tour of famous names can’t quite manage.

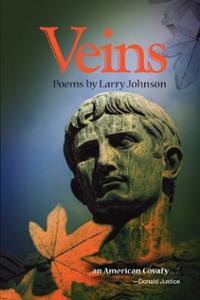

[Veins: Poems by Larry Johnson, by Larry Johnson (Cincinnati, OH: David Robert Books) 108 pp., $18.00]

Leave a Reply