Christopher Sandford of this parish is not only an adorner of these pages but has also garnered considerable status as a cultural historian. His inquiring eyes range widely, playing over everything from cricket to Kurt Cobain, the Great War to The Great Escape, Conan Doyle to Eric Clapton, and countless other late-19th- and 20th-century Anglospheric interests. Although conservative in some ways, he empathizes easily with unconservative subjects, or at least is able to tease out counterintuitive realities from modern myths. So in Satisfaction, his biography of Keith Richards published in 2004, he revealed such shocking truths as that the countercultural icon ne plus ultra likes few things better than Surrey and evensong, and that the large beakers of lethal-looking liquid carried ostentatiously onto many a reputation-tarnishing or -burnishing talk show actually contain iced tea.

In Harold and Jack (which I reviewed for Chronicles in February 2015), Sandford inspected the unexpectedly warm relationship between the stuffily Conservative Harold Macmillan and JFK, the acronymed epitome of 1960’s chic and “radicalism.” Now he plumbs more deeply Kennedy’s background, character, and development, underlining his earlier findings that the demigod of old Democrats was more manager than moralist, so anticommunist that he supported Joseph McCarthy, pragmatic on “civil rights” and heedless of early onset feminism, romantically attached to certain traditions, and conservatively conscious of what he described as “the abyss under everything.” All this is both intrinsically interesting and objectively important, as Kennedy’s attitudes help explain the whole course of postwar history, especially the persistence of the globally crucial American-British alliance, notwithstanding Suez and other potential points of cleavage. It is also elegantly told, full of sage asides and amusing observations, such as that on Alec Douglas-Home, “whose misfortune it was in the television age to resemble a prematurely-hatched bird.”

At the kernel of this story is the at times ambivalent relationship between JFK and his bluntly outspoken father, whose appointment in 1938 as ambassador to the Court of St. James seemed inexplicable even at the time. By October 1940, when he was replaced in this most important of postings by John Gilbert Winant, Kennedy père had made himself deeply unpopular with the British media, politicians, and even the public, called “Jittery Joe” for his acerbities about British preparedness and his advocacy of accommodating dictators, sneered at as likely crooked and as an arriviste as well as a snob.

His views were perhaps predictable from the head of a clan whose members clung to old Irish-American, anti-WASP resentments and never relinquished them, until at least the time of Ted Kennedy. JFK himself could switch on the Irish angle for domestic political purposes and sometimes drew parallels between the Irish-American and the experiences of other immigrants—but simultaneously, as Hugh Sidey noted, he “delighted in the romantic accounts of the rise of the British Empire, and the great figures on the battlefields or in parliament who made it possible.” JFK’s sympathy for those who felt alienated by WASP America was always tempered by distrust of their occasional overreaction, what he called the “venom and bitterness” of leftists like Harold Laski. In 1958 he wrote (or maybe typed) a booklet called A Nation of Immigrants, but like his equally insulated youngest brother he did not foresee what venomous and bitter use would be made of such vapidities.

Maybe it was also predictable that some of Joe’s high-spirited and intelligent offspring should have asserted their independence against so prickly a patriarch. Both Jack and his younger sister Kathleen footed it featly across high-society dance floors and (sometimes literally) into the arms of the aristocracy. Kathleen was dubbed “Debutante of 1938” by the press, and in 1944 she “assimilated” so far as to marry “Billy” Cavendish, Lord Hartington, against the wishes of her parents, who disapproved of both his Conservative politics and his Protestantism. (The marriage ended in the worst way after only four months, when he was killed by an SS sniper in Belgium.) The same season that saw Kathleen’s coming out also stood her older brother in good stead socially, although one dance partner, Deborah Mitford (later the Duchess of Devonshire and a close friend), found him “rather boring but nice.” (Her mother was more astute, saying, “Mark my words, I won’t be surprised if that man becomes President of the United States.”) Jack found he fitted in with a certain type of upper-class Englishman, sharing their sensibilities and tastes and sometimes even outdoing them in their stereotypical English attributes—lightly borne education, social ease, understated emotion, self-deprecating humour, easy-going sexual mores. Even at times of near-catastrophe Kennedy kept himself in check, for example saying of the overnight appearance of the Berlin Wall or the discovery of the Cuban missile emplacements that things were “quite tricky.” As the author observes, “There was a part of America’s thirty-fifth President, whether innate or acquired, that was more ‘English than the English.’” Kennedy seems to have recognized aspects of himself in the great English Whigs, rereading David Cecil’s masterpiece of 1939, The Young Melbourne, almost annually. Indeed, Victoria’s future first prime minister rather foreshadowed Kennedy in his flexibility, priapism, and privilege.

Like his historical hero, the clubbable, libidinous Kennedy had a serious side. Many remarked on his ability to switch in an instant from connubiality to Czechoslovakia, or the weather to the Wehrmacht, reading hungrily, meeting everyone who was everyone, watching Commons debates, and traveling on the Continent. His ideas did not always diverge that much from his father’s. Sandford cites an unsigned editorial in the Harvard Crimson written by JFK in October 1939 that called for compromise with “Hitlerdom”—but just two months later he was at work on what would become Why England Slept, in 1940 a perfectly timed anti-appeasement tract that became a best-seller. The book, written in a style that, Sandford notes, “could be suggestive of a light fog moving over a hazy landscape” and edited heavily by Arthur Krock of the New York Times, might never have been published had Kennedy’s father not promoted it—an example of the anomalies in their relationship: great loyalty, despite geopolitical disagreements. According to Paul Johnson, Joe Kennedy secretly bought up thousands of copies of his son’s book and cached them at Hyannis Port.

The friendships JFK forged before the war, the insights he accrued, offer insights into his indulgence of Britain at times when other Presidents might have lost patience with her. None of this means that the U.K. was ever anything other than a junior partner in the relationship, but possible Airstrip One humiliation was avoided owing to Kennedy’s understanding of Britain’s cultural-political position, his ability to get a hotline direct to Macmillan (Kathleen’s uncle by marriage), and to weekend with David Ormsby-Gore, the British ambassador whom he had befriended in pre-war London (to the disgust of Lyndon Johnson). Washington’s ambassador to London, David Bruce, was also congenial with Macmillan: The two reportedly beguiled lulls between phone calls during the Cuban Missile Crisis by reading Jane Austen to each other.

The President’s pragmatic and—occasionally—generous approach to British needs was also facilitated by Macmillan’s reciprocal pragmatism, as both leaders agreed on the awfulness of the Soviet system, the need for arms control and for orderly decolonization by the British, and the desirability of closer ties with Europe. Besides which, Britain was genuinely useful, with her global reach and sense of history, to the United States. Dean Rusk and other close American observers also appreciated the importance of Macmillan’s and Ormsby-Gore’s advice and support during the Missile Crisis. The President, Robert Kennedy remembered, “needed to unburden himself and listen to the man he’d come to privately know as ‘Uncle Harold.’”

There seems little doubt that Macmillan made a signal diplomatic contribution, if an unquantifiable one, during those “quite stressful” (this understatement is Macmillan’s) days. The goodwill engendered then still lingers in the Anglo-American ambience, even if the actual achievements of that period are few in number. (Sandford suggests that the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963 may be its only “imperishable event.”)

The book’s last chapter is largely an account of Kennedy’s last visit to England (in June 1963), piquant in its descriptions of dinner at Chatsworth, the “Palace of the Peaks,” in a fug of damp Labradors and cigars, poignant with the President’s visit to Kathleen’s grave at Edensor where he placed flowers and prayed in the Derbyshire drizzle—the more so because his own death was just five months away. As Macmillan recalls watching his “Dear friend” ascending by helicopter into a cloudless summer sky at the conclusion of the visit, it seems to him in retrospect almost as if he had witnessed a transfiguration. All that charisma, energy, and intelligence lifted away—and leaving so little behind, as America followed the United Kingdom in her fall from national greatness.

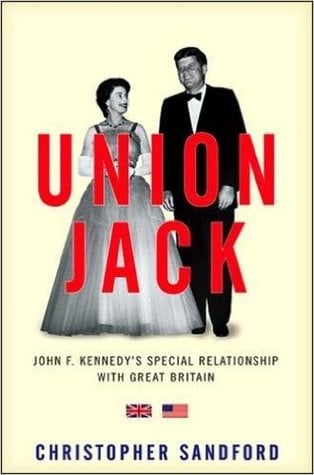

Joseph Kennedy and John F. Kennedy (AP Photo, File)

Union Jack: John F. Kennedy’s Special Relationship With Great Britain, by Christopher Sandford (Lebanon, NH: ForeEdge) 272 pp., $29.95

Leave a Reply