The Germans have a word for it: Schadenfreude. It means, literally, harm-joy, and refers to the nasty but common human tendency to rejoice when harm comes to someone else. In English, we don’t have the word, but we certainly have the phenomenon. Think of the nationwide jubilation over what happened to Richard Nixon (and, incidentally, to America) during the Watergate scandal. Today we have it again, with the media blitz over President Reagan’s Iran-Contra connection.

Europeans are often perplexed by the way in which America’s leading politicians and media figures seem to take pride in their ability to run their own country down and to hamper its effectiveness. There is such a thing as reasonable self-criticism, but to most Europeans, the American phenomenon involves Schadenfreude carried to the point of auto-déstruction.

It was not always so. The United States was once the home of jingoism: “My country, right or wrong!”—patriotism carried to the point of virtual blindness, when anything could be excused if it seemed to be in the national interest. Today we have the opposite phenomenon, in which breaches of every standard of confidentiality, civility, and honor are taken for granted, excused, even approved, if only they are not in the national interest and injure only our own nation. Most Europeans cannot understand the marathon flagellation of President Reagan because of the weapons-for-hostages/Contra funding deal. The frightful uproar over his visit to Bitburg cemetery two years earlier was even less understood. Nor can many Europeans understand why the United States gratuitously insulted Austria by declaring that Austrian president Waldheim cannot have a visitor’s visa to enter the USA, because of unrefuted allegations about his World War II record.

Why does there so often seem to be open season in the media—and in Congress—on America’s national interests? The American public is used to it and takes it for granted, like muggy weather in Chicago in the summer. Ostensibly, it is a quest for truth. To most Europeans, it looks like collective insanity. Part of the explanation must lie in our American illusion of invincibility. There was a time—perhaps for 20 years after World War II—when America’s military and economic might seemed so secure that one could chip away at it at will, from all sides, gaining fame and sometimes fortune without the risk of doing any serious damage. Those days are long past; the damage that has already been done to America’s interests is severe, and the damage that is still being done may suddenly prove fatal. But the tendency to self-destruct goes far beyond mere verbal self-abuse, however harmful that may be. It extends to deeds that we used to call treason.

We can compare what has happened to treason to the change of American attitudes on abortion. Up until roughly 1968, “abortion” was a loathsome word, and no physician wanted to be identified as an abortionist. After the Supreme Court decision in 1973, abortion became not merely acceptable but could even be called good—so much so that abortion activist Lawrence Lader could boast of 700,000 abortions in one year as a “triumph of the human spirit.” Something like this has happened to our attitude towards treason, although there has been no Supreme Court decision to justify it. We boast about our shame.

In The Treason System, Eric Werner analyzes a revolution in moral sentiment that has overtaken the West since World War I. In Divine Comedy, Dante reserved the lowest circle of hell for traitors, placing Brutus and Cassius, who betrayed Julius Caesar, in the same category as Judas, who betrayed Jesus Christ. Until well into the 20th century, treason was held to be the most loathsome of crimes. The historical Benedict Arnold was a cultivated gentleman, acting out of what he considered moral duty to his lawful king, but his name now symbolizes loathsomeness to generations of American schoolchildren. In France, the Dreyfus affair—in which a French army captain was convicted of selling military secrets to the Germans—became a national scandal. Later, when it was proved that this conviction was fraudulent, there was a second scandal. Had Dreyfus been convicted of murder, for example, and then exonerated, it would not have been such a cause celebre. The very idea of treason was shocking to pre-World War I France. Today, the story is different. Of course, treason is not considered exactly praiseworthy, but genuine traitors often arouse more sympathy than condemnation—witness the cases of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and of Alger Hiss in the United States.

For contemporary France, Werner cites a figure of 2,000 citizens involved in pillaging French defense secrets for the benefit of the USSR. This sort of activity is now more or less taken for granted. Offenders, if caught, will be prosecuted and punished, but national indignation over treason reaches nothing like the temperature caused in America by Watergate. Both the actual Watergate break-in and the subsequent cover-up were intended to be in the national interest. Perhaps if “the President’s men” had been plotting against the national interest—as in the Ellsberg and Pentagon papers case—the media would have been more sympathetic.

On the one hand, elected officials must not be allowed to place themselves above the law regardless of their motives; on the other hand, it is perverse to judge those who act out of patriotic motives more severely than those who aid our adversaries. Werner explains it thus: “Treason has become part of public morality; it has become democratized.” Treason not only no longer causes scandal; it is hardly even acknowledged to exist as a sociological phenomenon—rather like heresy in the modern church. Who can be called a heretic today? Hardly anyone, because no one knows what orthodoxy is. One of the difficult things to communicate is the fact that a major phenomenon—which earlier ages would have called criminal—has virtually disappeared from public awareness: the parallel with heresy and with abortion is evident.

“With over 2,000 documented cases of treason in France, one would suppose that treason would be the subject of books, of research projects, like any other sociological phenomenon of similar magnitude. But where are they? We cannot study treason because there really isn’t any such thing. . . . Fifty years ago, traitors knew what they were doing. They realized that treason is a crime, and that they risked death if apprehended. Today accused traitors are surprised, shocked, outraged. They would faint from astonishment if told that they deserved hanging. ‘Hanging? But why hanging? What have we done wrong? We are democratic. We are defending human rights.’ And all around people would nod approvingly.”

A former director of the French counterespionage service, DST, entitles his memoirs Mission Impossible and writes: “The concept of duty to one’s country appears so outmoded that no one is outraged or even surprised when a prisoner, condemned to life imprisonment for treasonable acts of extreme gravity, is freed after five years.”

It is not necessary to be an idealist, a committed partisan of the other side, nor even to be highly paid to become a traitor. One sometimes has the impression that treason is committed simply for want of anything better to do. One former Swiss officer. Colonel Jeanmaire (the highest peacetime rank in the Swiss army), is in prison for giving Switzerland’s aerial defense plans to the Soviet Union. For his services, the Soviets gave Jeanmaire nothing but a cheap television set.

There are parallels in the United States: Career U.S. Navy personnel sell secrets to the Russians; Marine guards admit Soviet agents into the secrets of our Moscow embassy. In the first case, financial problems furnished the alleged reasons; in the other, sexual enticement. Nineteenth-century newspapers would have raged at such venality. Today we seem to feel that almost any enticement suffices to make treason understandable, if not praiseworthy, no weightier than sexual infidelity in the entertainment world.

Treason has become a generalized phenomenon if not a way of life in the West. But how can this be explained? Werner’s answer deals with France, but it is thought-provoking—and alarming—when applied to the English-speaking world, particularly to Britain, Canada, and the United States: Treason exists only where there is something to be betrayed. We no longer take treason seriously because we no longer believe that a nation is something that can be betrayed. (Abortion can be a crime only if a baby exists to be killed; heresy can be a sin only if religious truth exists.) “A traitor is not really a traitor because the nation is not really a nation.”

Not a nation? France, General de Gaulle’s “grande nation,” not a nation? The United States, which we sometimes still call “the world’s most powerful nation,” not a nation? In Werner’s sense. No. Both France and the USA are states, but not states of the kind that can inspire national loyalty. Hence, “La trahison, c’est la chose la plus naturelle du monde.”

What can inspire loyalty? A nation can, and so can an empire, but modern Western countries are neither. A nation is an ethnic and cultural entity and must also have its own national spirit. France was a nation, and so was Britain; Germany really became a nation only in the mid-19th century, and this late maturation helped plunge Europe into two world wars. Nations frequently seek “natural boundaries,” but they do not necessarily seek to expand beyond them.

An empire has a different kind of spirit, universal rather than local. Rome, the empire par excellence, began as one city-state, not very different from most of the rest of Italy. Its tremendous expansion was not national—like France’s in the 17th century—but imperial. Rome developed military competence and a high level of administrative and management skills, but these alone would not have created and maintained the empire; For centuries Rome stood for something grand, and scores of communities and races that were strangers to each other came to share its vision. Hitler’s “Third Reich (empire)” was doomed to fail as an empire because Hitler insisted on the narrowest kind of nationalism. No one but ethnic Germans could share it.

An empire need not try to rule the world. Rival empires can coexist side by side, as the British and French Empires did prior to World War II. Both were convinced that they had something to give the world, but they were not determined to impose it on each other. In Britain and France, both when they were relatively homogeneous nations and as they became empires, treason was a high crime. Why is it such no longer? Because they have abandoned their empires and have not reestablished themselves as nations. Hence, treason is “la chose la plus naturelle du monde.”

Can an empire revert to being a nation? France has tried. De Gaulle, giving up his country’s imperial heritage, made a conscious effort to reestablish France as la grande nation. But it was apparently too late. France can no longer be a nation because too many survivors of her imperial past have installed themselves in the “hexagon” (as France is often called after its shape on the map).

France might like to be complete and self-contained, like a hexagon, and no longer have need of an empire. Unfortunately for France, this no longer seems to work. Modern France may be a self-contained hexagon geometrically, but not spiritually or culturally. France has opened its doors to non- French, non-Catholic, non-Christian, non-European immigrants in great numbers—the shipwrecked victims of its vanished empire. For the empire, people of diverse traditions with strong attachments to France were an asset—for the hexagon, they are a liability. A missionary, expanding, evangelizing church is proud of its converts from other religions; a stagnant church is embarrassed by anyone trying to convert, because he reminds the existing “believers” that they have lost their vision. Jews who want to accept Jesus as their Messiah are embarrassing to “Christians” who no longer believe that Jesus is “the way, the truth, and the life.” Vietnamese and Africans who want to be loyally French embarrass ethnic Frenchmen because they remind them of their lost (or betrayed) empire, while those who do not want to become French remain a foreign body and lead to nationalistic reactions such as that led by Jean-Marie LePen. Can France be a nation when its population numbers 15, 20, 25 percent of nonassimilated immigrants, particularly of immigrants who came because they believed in an ideal that the majority has abandoned?

There is a warning for the United States in all this. Like Rome, we have never really been a nation; unlike Rome, we have not really become an empire. For a brief period after the Second World War, the United States had a chance to become an empire. We turned away from that chance, with all its inherent potential for grandeur and for evil. The postwar “imperialism” of which America is accused has been commercial only—and business is not empire.

America has made an attempt or two to act like an empire, even if unconsciously. America’s Korean War may be compared to Rome’s interventions in Greece: The Korean War made sense on the assumption that America has a mission in Asia. It made much less sense on the official theory that our only goal was to help Asians attain self-realization. This became our stumbling-block in Vietnam. Our persistent refusal to see the Vietnam War as a clash of empires and our denial that America has any legitimate imperial mission or interests made it impossible for us to justify our presence in Vietnam to our own people. We deny that we are an empire; at the same time, we permit or promote the practice of the melting-pot in ethnic and cultural pluralism, which makes it impossible for our country really to be a nation. What is left? The Treason System.

To return to the religious parallel: Committed Christians have always known that there are only two choices for the church. It will either have a mission to the world, or it will suffer submission to the world. To abandon the sense of mission is to reduce Christianity to the level of folk religion or popular superstition, making the church little more than a folklore club. Something similar holds true with our American “empire”: either it will have a sense of mission or it will decline to a constantly diminishing role in the world.

The United States, by virtue of our power, wealth, and dynamism, simply must have a worldwide influence in the late 20th century A.D., just as Rome had to have such in the third century B.C. Unfortunately, now our influence is commercial only; it is no accident that the Iran-Contra imbroglio, which involves—and menaces—our legitimate imperial interests, revolves around a financial “deal”—arms to a hostile tyranny in the Middle East for cash to help overthrow a hostile tyranny in Central America. “Send in the Marines!” appeals to quite a different kind of spirit from “Send a Marine to collect the cash.” Even so, the phenomenon of one loyal if misguided Marine officer standing up for our national interest still inspired the nation. As movie critic Fredy Buache of Lausanne wrote some years ago, “If you deprive people of genuine fervor too long, a little orange syrup will bring them to tears of emotion.” Unfortunately, the orange syrup hardly works at all with the media or most of our political leaders, and it simply is not a wholesome diet for the nation for any length of time. Can we inspire respect beyond our borders when we have such difficulty inspiring loyalty within them?

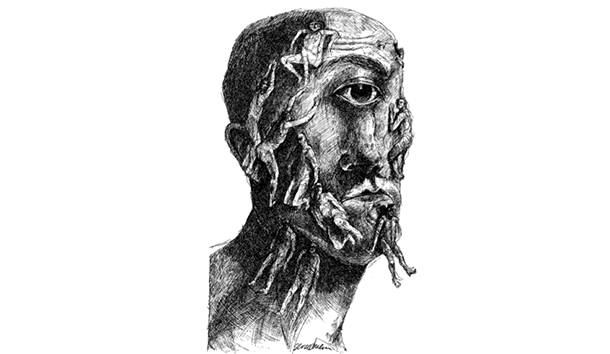

Werner’s analysis is alarming: Like the diagnosis, AIDS-positive, it seems to point to inevitable debility and death for postnational “nations.” What Werner calls the “democratization of treason” is rather like the generalized immune deficiency of AIDS. The body’s ability to fight disease is destroyed, and death becomes inevitable. Medical researchers are frantically seeking a vaccine against AIDS. Can we find a vaccine against spiritual AIDS? Treason is a spiritual immune deficiency, and the vaccine—if there is one—will have to be spiritual.

Treason is a social symptom of a spiritual disease. A naive society, before the days of the electronic “global village,” could thrive on its national substance. A society where all values are “up for grabs” cannot. As Hans Millendorfer of Studia Austria says, “A value-free (wertfrei) society is valueless (wertlos).” The Communist world is not a “nation,” but it does have its own perverted “imperial” vision. The traitors of the West pay homage, consciously or not, to the superiority of that perverted vision. We cannot rid ourselves of treason unless we can produce a better one. The intellectual wing of conservatism is ill-advised to be supercilious towards the attempts—however inelegant—of groups like the “Moral Majority.” Jerry Falwell may not have the whole answer, but Norman Lear and “People for the American Way” certainly have no answer at all.

[Le systeme de trahison (The Treason System), by Eric Werner, Lausanne; Switzerland: L’Age d’Homme]

Leave a Reply