“We are born with the dead / See, they return and bring us with them.”

—T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding”

“The philosophical and ideological currents of a period necessarily affecting its imaginative literature,” wrote Russell Kirk in “A Cautionary Note on the Ghostly Tale,”

the supernatural in fiction has seemed ridiculous to most, nearly all this century. Yet as the rising generation regains the awareness that “nature” is something more than mere fleshly sensation, and that something may lie above human nature, and something below it—why, the divine and the diabolical rise up again in serious literature. In this renewal of imagination, fiction of the preternatural and the occult may have a part.

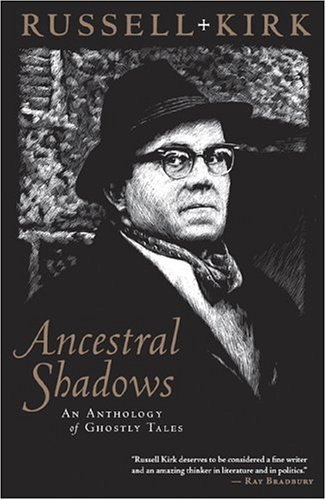

In the renewal of that fiction, Dr. Kirk—better known as the author of The Conservative Mind and one of the founders of the modern American conservative movement—tried to play his part. The stories collected in Ancestral Shadows: An Anthology of Ghostly Tales are only 19 of the dozens of fantastic tales that Kirk published in his lifetime and an even smaller portion of the scores of stories that he told to family, friends, and even the passing strangers to whom he so frequently extended his hospitality. While his political and historical works vastly outweigh these tales in both number and influence, Kirk himself knew that his fiction could more directly shape the moral imagination. And it has had the opportunity to do so: While The Conservative Mind has remained in print since its first publication in 1953, it is not Kirk’s best-selling book. That honor belongs to The Old House of Fear (1961): Though no longer in print, this gothic horror novel has sold more copies than all of Kirk’s other books—combined.

So why is Kirk’s fiction not better known among self-identified conservatives? The first answer, sadly, is that most such people do not read fiction—and, all too often, they take great pride in saying so. The other answer, equally important, is that Kirk’s fiction is truly conservative, and self-identified conservatives today simply aren’t. National Review’s John J. Miller has, in recent years, recommended Kirk’s fiction to NR readers, but when Kirk’s memoirs, The Sword of the Imagination, were published in 1995, Miller scoffed at Kirk’s belief in ghosts. What kind of progressive, compassionate, big-government, national-greatness conservative can believe that “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy”? Let such thoughts in, and uncertainty may follow, and then what would happen to our ability to act?

Such uncertainty surrounds us every day, and it is only the ideologue—a creature of the left, whether he calls himself a Marxist or a conservative—who can see the world entirely devoid of shades of gray. Shadows are never uniformly black, and if the hard lines of rationalism are allowed to give way to fear—either the salutary fear of the Lord or the fear that arises naturally from our fallen human nature—we may soon find that we perceive in those shadows more than just the play of light. And since, throughout the centuries, man has believed those perceptions to be glimpses of a greater reality, who are we to be certain otherwise?

In opposition to the rationalist and the ideologue, Dr. Kirk had his own certainty—or perhaps it would be better to say his own faith, “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things unseen.” For him, ghost stories were not simply a reflection of an unseen world—which could, of course, simply be horrifying, as in the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft—but an expression of his hope of a life beyond this life, of the existence of Purgatory, even more so than of Heaven. “No doctrine is more comforting than the teaching of Purgatory,” he wrote in his memoirs, “ . . . [f]or purgatorily, one may be granted opportunity to atone for having let some precious life run out like water from a neglected tap into sterile sands.”

The best stories that Kirk wrote draw fully from the font of this comforting doctrine. They do so without being didactic—in his fiction, Kirk rarely uses the word Purgatory. But what else could you call the hotel in “Saviourgate” (1976) in which Mark Findlay, a man down on his luck (“In more ways than one, he had lost his sense of direction”), a failure at his responsibilities, contemplating suicide in a railway station, finds himself for an evening, before deciding, for the sake of his sick wife, to pull himself together and travel to London for a business meeting:

For Marian must not be left to suffer alone, and there were the sensibilities of railway porters to think of. Hyde Park breakfast or no Hyde Park breakfast, something yet might be accomplished in London with somebody or other—given will, given spirit, given grace. Behind this evening’s charade there had moved some quickening power, some hint or glimpse of hope. How a man dies, and with what justification: this absurd interval of talk had wakened Findlay to awareness of such matters. He would not plunge himself into nothingness without another effort or two.

One of the men Findlay encounters in his brief sojourn between life and death is Ralph Bain, a recurring character in Kirk’s stories who, while bearing no physical resemblance to Kirk, has, like another recurring character, Manfred Arcane, a strong spiritual likeness to his author. We first meet Bain in “Sorworth Place” (1952), one of Kirk’s earliest stories. (Rod Serling made it into an episode of Night Gallery in 1972.) A great hulk of a man, injured in the head in “the war,” Bain drifts from town to town throughout Scotland, living a sort of Purgatory on earth, until he meets Ann Lurlin, a beautiful widow. For his unrequited love of her, he finds himself, one horrifying night, entering the true Purgatory.

Two of the best stories in this volume, “There’s a Long, Long Trail A-Winding” (1976) and “Watchers at the Strait Gate” (1980), feature other recurring characters—Frank Sarsfield, another wanderer, and Father Justin O’Malley, one of the last good Catholic priests, exiled by his bishop to Anthonyville, a rural outpost suspiciously similar to Kirk’s own beloved Mecosta, Michigan. Indeed, these stories draw on the places and people that Kirk knew well: The house in which Frank takes refuge from a snowstorm is clearly Kirk’s New House at Piety Hill, shaped out of the brick addition he had built on to his ancestral home before the latter burned to the ground on the night of Ash Wednesday, 1975. Frank himself, Kirk acknowledged in his memoirs, is Clinton Wallace, a hobo “who lived with the Kirks for six years and then was buried in their family plot.” It was Clinton who was responsible for the great fire: Instructed by Kirk to bank the embers in the fireplace for the night, Clinton had taken the easy way out and left a huge fire blazing. When the chimney collapsed, the wooden structure was doomed.

“There’s a Long, Long Trail A-Winding” is more than a ghostly tale; it is, in a way, a literary Purgatory for Clinton Wallace, who, in the guise of Frank Sarsfield, redeems his dislike for physical labor that resulted in the destruction of the Old House through violent action that saves the lives of the fictional family that resides in the New House. In his stories, Kirk did not simply seek to entertain; in a manner that any accomplished narrator would understand, he completed his own life, setting wrongs aright and providing meaning to seemingly random events, such as the kidnapping of his wife, Annette, which forms the basis for “The Princess of All Lands” (1979), another story collected in this volume.

(“There’s a Long, Long Trail A-Winding” won the World Fantasy Award for best short story in 1979, besting a story by Fritz Leiber, the great science-fiction writer, who had won the World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement just the year before, proof—if any was needed—that Kirk was no amateur in his art.)

These ghostly tales are, alas, not uniformly masterful. While Kirk wrote in “A Cautionary Note on the Ghostly Tale” (reprinted here at the end of the book; it might have served better as an author’s foreword) that “I do not ask the artist of the fantastic to turn didactic moralist,” there is, unfortunately, really no other way to interpret the manner in which he disposes of the protagonists of the first two stories in the collection, “Ex Tenebris” (1957) and “Behind the Stumps” (1950). Both men are government agents, not simply caught up in bureaucracy and swept along by progress but relishing both. When they meet horrifying ends for the sin of being nothing more than modern men, we may take some pleasure in their demise, but it is a perverse pleasure that we know we should not indulge. Hollow men, these agents will have much to answer for in the next world; but there is something unsettling about the glee with which Kirk hastens their demise.

Since both stories were written while Kirk was still in his 30’s, they can be excused as expressions of the zealousness of a young man. Even Russell Kirk, whose biographers often make him sound as if he entered the world full-grown, matured with the passing of the years. It would, therefore, have been useful if Vigen Guroian, the editor of this volume and the author of its superb Introduction, had dated the stories or provided a timeline of their publication. (The publication dates I have noted are drawn from Charles Brown’s excellent Russell Kirk: A Bibliography, which unfortunately only runs through 1981.)

That “Ex Tenebris” and “Behind the Stumps,” both published originally in English mystery magazines, were well received by readers who likely did not consciously regard themselves as conservative (and therefore would not have been expected to revel in the destruction of progressive men) illustrates a point that Kirk would immediately have understood. In his fiction, as in his other works, Kirk, like Irving Babbitt before him, stresses the importance of both imagination and will over reason. While self-identified conservatives may not naturally gravitate toward the ghost story, those whose imaginations can conceive of a world of shadows are more likely to be, however unconsciously, more conservative—which is to say, since Kirk regarded conservatism as the absence of ideology and ideology as the distortion of human life, more fully human.

Still, the moralism of these two stories indicates that Kirk himself was not untouched by ideology—or at least by the occasional failure of imaginative sympathy. Later, when he chose as the subject of his stories people and places that he knew intimately, this moralism disappears, never to resurface. Manfred Arcane (clearly an avatar of Kirk) can act heroically, even though he is, by his own account, a flawed man.

For those who are familiar with Kirk’s other writings but not with his fiction, there are some moments of surprise and delight in this volume. While most of the stories are narrated in a voice that is recognizably Kirk’s, a few, such as “Lex Talionis” (1979), “The Reflex-Man in Whinnymuir Close” (1984), and “An Encounter by Mortstone Pond” (1984), beautifully illustrate what Kirk could do when he deliberately set aside his 19th-century literary style. He had demonstrated his versatility previously in A Creature of the Twilight: His Memorials (1966), in my opinion the best of Kirk’s novels and one which is disturbingly fresh in a world in which the United States has arrogated to herself the role of the world’s policeman. While A Creature of the Twilight tells the story of Manfred Arcane, Minister Without Portfolio of Hamnegri, as he struggles to restore order in this small African country which, through a coup, has become a battleground for the great powers, Kirk skillfully switches the narration back and forth, chapter after chapter, between the voices of a dozen different actors, from Arcane himself, to an American State Department diplomat, to radio and newspaper correspondents (with subtle and uncanny differences of style for each one), to an American mulatto from Georgia, to three women ranging in age, experience, and beauty. In the entire novel, he strikes not a single false note, and reading Kirk’s similar deftness in these three stories, I found myself wishing that he had stretched the bounds of his style more often.

For those who have read A Creature of the Twilight and Kirk’s final novel, Lord of the Hollow Dark (1980), there are some pleasures here as well, because we have collected in one place the stories of Ralph Bain and Manfred Arcane that tie the two novels together. While Kirk stretched the back story of Arcane beyond the breaking point to allow him to become the hero of Lord of the Hollow Dark (there is no plausible way to reconcile Arcane’s account of his father in the latter book with that in the former), “The Last God’s Dream” (1979) and “The Peculiar Demesne of Archvicar Gerontion” (1980) help explain how Arcane arrives in Scotland, the setting of Lord of the Hollow Dark.

In his Introduction, Guroian describes “An Encounter by Mortstone Pond,” the final story in this volume, as “Kirk’s little masterpiece, a haunting evocation of how time and eternity meet in the human soul and consciousness, wherein also God is present and speaks to the person.” This remarkable gem is, as they say, alone worth the price of admission. Contrasted with “Ex Tenebris” and “Behind the Stumps,” it shows clearly how Kirk’s fiction and his thought as a whole deepened and matured over the space of some 40 years. The shortest of the stories, it is also the simplest in both language and action, and yet, in recounting two incidents, 50 years apart, in the life of one man as he walks along the shore of Mortstone Pond, it reveals a spiritual depth that rivals the greatest of Christian literature. It bears reading, and re-reading, and then reading once again. Thankfully, with the publication of this admirable volume, we can all keep it close at hand.

[Ancestral Shadows, by Russell Kirk (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company) 406 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply