America’s bad poetry is a consequence of the reduction of higher education into merely another arena for the politics of class, race, and gender.

Modernist education is a bridge to nowhere. This is so almost by definition because modernism holds no transcendent aim for man nor even any reliable bedrock of human truth upon which to build.

That explains the airy pomposity of all the college advertisements and websites you will encounter, full of the language of “leadership” and “political change” and very short on any frank assessment of what man is, what he can and cannot accomplish, and where he is going. “O how unlike the place from which they fell,” says Milton in Paradise Lost about the first rhetoricians of the air, the rebel angels. Such is the fall from a classical and Christian education, and the political wisdom and cultural richness it could engender, to what passes for such in these latter days.

Let me tell a story by way of illustration. In the spring of 1981, when I was about to graduate from Princeton, the professor of our 17th-century literature class, Earl Miner, invited me and my classmates to end the term with dinner at his home. Professor Miner loved all things Japanese, for the precision, delicacy, and intelligence of their forms, and that fit very well with the British poetry he taught. A similar elegance strikes one immediately when reading such poets as George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, and Andrew Marvell: the form is integral to the meaning. This is no restriction, however. Just as stone pillars and arches, set in place with only the mortar of gravity to bind them, did not restrict Roman architects when they built their aqueducts.

As we sat on the floor of Miner’s parlor at our Japanese dinner, we might have guessed that if there were going to be some poetry recited, it would be poetry of beautiful and significant form. Maybe Japanese haiku, with tremendous meaning, suggestiveness, and beauty pressed into a small space, like a bonsai tree of the heart and mind. Instead, he brought out a book of verse by a 19th-century Scotsman, William McGonagall—widely recognized as the worst poet ever to write in the English language.

I daresay that many a contemporary poet would give McGonagall a run for his money. Indeed, I will shortly provide an example from our current political scene. But for sheer earnestness wedded to unintentional humor, my vote still goes to the Scot.

McGonagall shows no sign of having read English poetry, and certainly no sign of the classics. I don’t blame him too much for that gap in his education. Not everybody has the opportunity to study Dante and Virgil, though it would have been easy for McGonagall to pick up a book of English poetry by his contemporary, the immensely popular and classically educated Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the poet laureate of England. He might have learned a few things about the art, not that he would have improved his own (for that, I believe, is hardly possible!). But he might have been inspired to leave poetry to the poets and to do something more useful with his time. So, too, do I have a dream, that a single member of our Congress, perhaps a feminist perpetually short of breath, might happen upon the writings of a Daniel Webster or Robert Young Hayne and be so abashed as to take up gardening instead of political oratory or something else that really does conduce to the good of mankind.

In any case, Miner handed the book to me, and he asked me to read a poem called “The Tay Bridge Disaster.” That was one of the things McGonagall, a teetotaling moralist, liked most to write about: drunkenness and disasters. If there was a fire in Scarborough, or if a little blind girl was beaten to death by her drunken father, McGonagall would be on the spot to moralize about it in verse. That is what he did after a railway bridge over the Tay River, in the midst of a terrible winter storm in 1879, collapsed under the weight of a crossing train at the cost of some 70 lives. Here is how that worthy poem ends:

It must have been an awful sight, To witness in the dusky moonlight, While the Storm Fiend did laugh, and angry did bray, Along the Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay, Oh! ill-fated Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay, I must now conclude my lay By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay, That your central girders would not have given way, At least many sensible men do say, Had they been supported on each side with buttresses, At least many sensible men confesses, For the stronger we our houses do build, The less chance we have of being killed

At which point I flung myself back flat on the floor in a helpless fit of laughter, and so did everybody else.

I shouldn’t be too hard on William McGonagall. He had not an ounce of guile in his soul. A couple of mischievous undergraduates once wrote to him saying that they were aspiring poets, too, and asking him his advice. When it came to learning the art, should they turn to the Shakespearean method or the McGonagallian method? I do not recall whether he replied to the letter. If he did reply, I have no doubt he was earnest about it.

McGonagall had no sense of form, no salutary fear of pomposity, and no suspicion of the ridiculous. The music of poetry, for him, was entirely bound up with rhyming, no matter how long the lines or how repetitive and uninteresting. Nor could he find an intelligent and meaning-opening metaphor to save his life.

But I think that many people who are called “spoken word poets” in our time are no better than he was, though a lot less innocent. This is a characteristic excerpt from the poem titled “The Hill We Climb” read by its young author—I do not wish to smear her name—at the presidential inauguration of 2021:

Scripture tells us to envision that: “Everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree, And no one shall make them afraid.” If we’re to live up to our own time, then victory Won’t lie in the blade, but in all the bridges we’ve made. That is the promise to glade, The hill we climb, if only we dare it: Because being American is more than a pride we inherit— It’s the past we step into and how we repair it. We’ve seen a force that would shatter our nation, rather than share it. Would destroy our country if it meant delaying democracy. And this effort very nearly succeeded. But while democracy can be periodically delayed, It can never be permanently defeated. In this truth, in this faith we trust, For while we have our eyes on the future, History has its eyes on us.

I grant, it isn’t as silly as McGonagall’s work, but silliness is at least sometimes a pleasant thing, like the patter of little children. “The Hill We Climb” is far more pompous than anything McGonagall, a devout Christian and therefore at least fitfully aware of his own follies and sins, could have conceived. Like McGonagall, the author has no sense of poetic form, no sense of the music of the line, no knack for imagery, and no salutary fear of the trite. McGonagall’s River Tay was “silv’ry” even when it was roaring against the bulwarks of the bridge it cast down, and so too our author here can’t resist casting her “eyes on the future,” or using “democracy” as a talisman, or, with real hysteria, suggest that our sluggish old nation, wealthy and fat and not too virtuous, was about to be shattered, except that Joe Biden, plagiarist, grifter, and muddlehead, stepped into the breach.

Our youth poet laureate does not seem to know what the phrase “in the blade” means, while the use of “glade” as a verb clanks like an old car’s drive train giving way and scraping on the asphalt.

McGonagall’s grammatical sense left him for the sake of a rhyme when he wrote that “sensible men confesses.” Likewise, our youth poet laureate does not seem to know what the phrase “in the blade” means, while the use of “glade” as a verb clanks like an old car’s drive train giving way and scraping on the asphalt. [The spoken version of the poem and the versions that appeared online after the inauguration indeed contained “to glade” as if it were a verb; when Viking Books published the poem in 2021, the line was changed to “promised glade.” –Ed.]

How does one write so badly? Is it a breach in one’s education? McGonagall did not learn from Virgil and Dante, the classical Roman and the Christian, and neither has she. McGonagall would not have despised the elder poets; he simply didn’t know about them. He lacked the advantage of a university education, which nowadays instructs young people on how to despise their elders. If McGonagall’s poems were bridges, they would all collapse like the one over the Tay—but at least he would have been sorry for the collapse. Unlike America’s first National Youth Poet Laureate, he did not set about to construct wreckage.

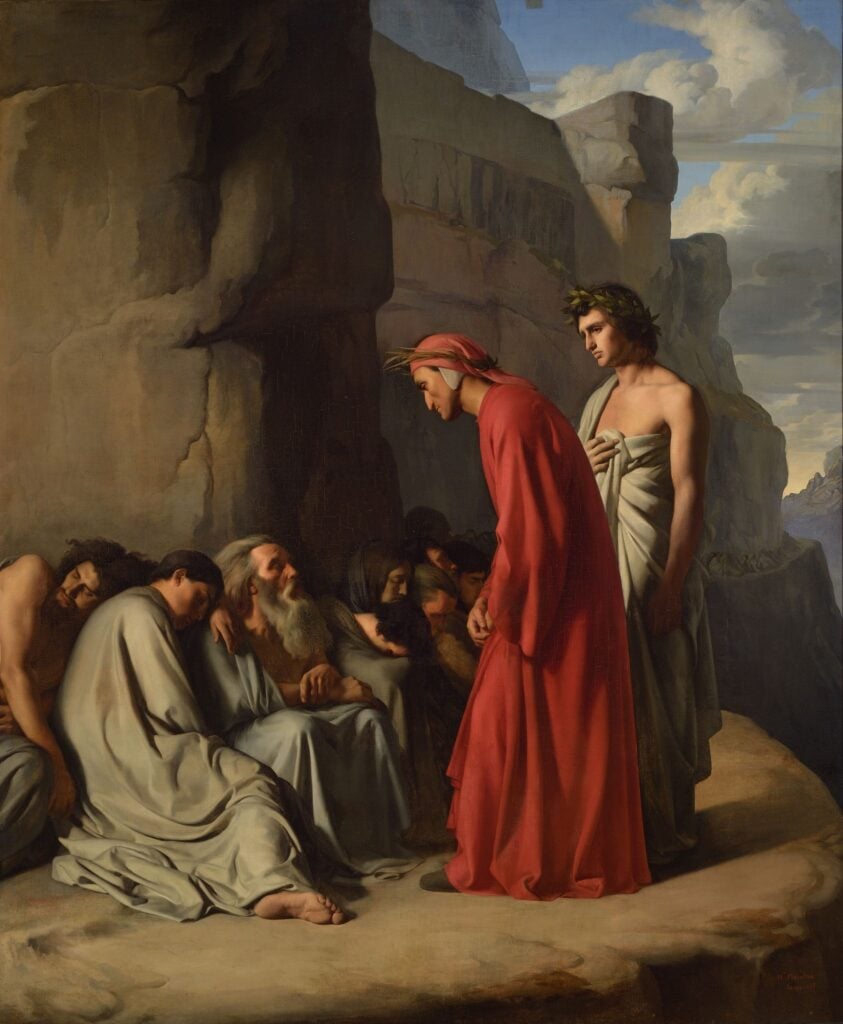

But it does not have to be so. Here I turn to an important moment in literary history: to a most generous Christian approach to the wisdom and the art of the ancient pagan world. In the second book of the Divine Comedy, Dante and Virgil ascend to the summit of the Mount of Purgatory. Now, it should be borne in mind that this region of the hereafter is itself profoundly poetic, in several ways at once.

In Dante’s depiction of Hell, there is no music, no singing. Dante, of course, had no experience of television jingles, so I cannot say for certain whether, if he were writing now, he would pipe such things in for the greater agony of the damned. If some people are to be sent to Hell for their crimes against music, it may yet be an unjust torment to compel other people, such as loan sharks, murderers, and traitors, to have to listen to it. But there is music in Purgatory—the music of hymns. It is one of the first things Dante shows us about the realm. The souls crossing the ocean to the shores of the mountain are all singing “When from the land of Egypt Israel came,” the psalm typically chanted as pallbearers bear the bodies of the deceased from the church to the burial ground (Psalm 114). They sing it joyously; it is a song of liberation, their liberation from sin and death.

Poetry, too, is one of the objects of interest for many of the souls in Purgatory. In Hell, once you are past the circle of the virtuous pagans and the unbaptized children, no one evinces any interest in poetry, and that goes for such well-known poets as the suicide Pier delle Vigne, the sower of discord Bertran de Born, and Dante’s own elderly mentor, the sodomite Brunetto Latini. But in Purgatory, quite a lot of people want to talk about the art—they are passionate about it. So, for example, when Dante is in the circle of the gluttons, and he meets the soul of a rival poet, Bonagiunta da Lucca, what else do they talk about but poetry? Bonagiunta had attacked the new generation whose love poetry was characterized by philosophical and theological terms, those that would make a work like the Divine Comedy conceivable. In life, he dismissed the learned poetry of Dante’s predecessor, Guido Guinizelli:

You who, for the delightful songs of love, Have altered all the manner and the style, The form, the very being, that you might Gain a surpassing place beyond the rest: You’ve done as little as a candle does, Shedding a candle flicker in the dark, Which fails before the light of that high sphere Surpassing every light in radiance. Surpass all men you do—in subtlety. So obscure is your chatter, you can’t find Anyone to make heads or tails of it. They think it just won’t fit—though you do fetch Your meanings from the doctors at Bologna— To dredge a song out of those learned tomes.

What to do with this Bonagiunta, then, if you are to meet him in the world beyond? Dante was an effective avenger if there ever was one, and in Purgatory his vengeance takes the form of an odd generosity and mercy. For he has Bonagiunta himself praise the “sweet new style” of the poetry he had once mocked, poetry deeply indebted to the hard-won accomplishments of human learning. It is Bonagiunta da Lucca who recognizes the younger poet, who predicts that Lucca will prove a refuge for him when he is exiled from his native Florence, and who then asks this urgent question:

But do I see the introducer of the new songs, and the verses that begin, “Ladies who have intelligence of love”?

Quite a celebrity, then, our Florentine poet is. But Dante defines his work in a way that is confident and humble at once:

I’m one who takes the pen when Love breathes wisdom into me, and go finding the signs for what he speaks within.

In other words, Dante the poet is an amanuensis of Love. The content of his poetry, he implies, does not originate in his own mind and soul but rather from Love itself, and what the poet then does is to find the means to convey that truth. The poet is not a creator but a sign-finder, and as a sign-finder he opens himself up to the divine. He is, as it were, the architect of a bridge between earth and heaven—not by his originality, and certainly not by political action, but by his following the wisdom of the truths that Love opens up to him.

Bonagiunta then acknowledges the difference, and he is quite satisfied by the explanation:

“Now I see well how all your pennons fly faithfully following him who speaks to you— with our wings this was surely never so; Yet if you wish to see the matter through, you’ll find no other difference in the style, ”and he fell silent, as if glad at heart.

It was not poetic talent or linguistic cleverness, then, that divided Bonagiunta from Dante and his fellows but a failure to acknowledge, or to turn to, the source of true poetic inspiration.

But I have yet to mention the most important way in which Purgatory is poetic. The realm itself is the sort of sign Dante says it is his work to go about finding: it is itself that meaning-bearing bridge between the human and the divine. For Purgatory is exactly opposite the globe from

another mount, that of Calvary, which makes the mountain of Purgatory a human place once more. It is a prison of liberation, an infirmary for strengthening the soul. You cannot go there by your own power. Ulysses, as Dante imagines him in Hell, once made the attempt, unwittingly, and he and his men were swallowed by the sea just after the mountain came within sight. We may say that a whole ocean of God’s grace lies between the earth we inhabit and this mysterious and strangely beautiful mountain.

Over and over, the souls in Purgatory are instructed in love, or in the trust that love entails: the envious must literally rely upon one another as they sit close to the side of the cliff, because their eyes are sewn shut with iron wire, and the precipice falls off only a few strides away. The slothful race about and encourage one another with shouts, “Come on, come on, don’t let time slip away / For lukewarm love!” If heaven is, as Piccarda will say to Dante in Paradise, “to live in loving, necessarily,” then Purgatory is well conceived as the realm where the power and the desire to love are built up, and souls grow ready to approach the ultimate source and end of their love, which is God.

But just as it is men whom God redeems, and as grace builds up nature rather than supplanting it, so too all the good things man loves are restored to him, and that is why it is most fit for Virgil, the pagan poet who did not know the revelation of Christ, to meet a fellow Latin poet, Statius, whom Dante imagines as having become a secret convert to the Christian faith. Statius does not know yet whom he is walking beside, so that when he identifies himself as the ancient poet who most followed in the footsteps of Virgil, it is as an utterly innocent and spontaneous act of gratitude and love:

“The brilliant seeds that set my love afire flashed from the divine flame that kindled me and lit the lamps of many a thousand more— Of the Aeneid I mean: for all I am of poet, it was my mama and my nurse; without it, all my work weighs not a dram. And I’d consent to spend an extra year, could I have lived on earth when Virgil lived, suffering for my sins in exile here!”

This is no mere formal compliment. Dante really does suggest that the poetry of Virgil, pagan though he was, was divine: it came from God, whether or not Virgil was conscious of it. In fact, when Virgil goes on to ask Statius how he came to be a Christian, Statius stuns him with his reply. Virgil’s own words in his fourth eclogue—those which speak of the birth of a divine child who will rule the world—interpreted in a way that Virgil himself could hardly have suspected, seemed to Statius to chime with what the early Christians were teaching. It was a bridge for Statius. “Per te poeta fui, per te Cristiano,” he says, echoing, unawares, the inscription over the gates of Hell. It is no longer “Through me one enters into the sorrowing city” (Per me si va nella citta dolente), but “Through you I became a poet, through you a Christian,” or, as I have translated it into verse, “A poet you made me, and a Christian too.”

What I want to say here may seem a bit too bold, but I think Dante has set the suggestion before us, or has built the bridge for us to cross: To become a poet and to become a Christian are not exactly two separate things. Poetry, insofar as it is true and beautiful, cannot of itself lead man to God, but it can serve as the bridge whereby man comes to knowledge of God. Not, again, because the individual poet is clever but because the art is what it is, in the grace and the providence of God.

J.R.R. Tolkien said to C. S. Lewis, by way of leading his friend from doubt and despair to the Christian faith, that the powerful and beautiful myths of the pagan poets were like “good dreams,” full of a phantasmagoria of errors, but still oriented toward the truth. Thus, the Christian need not give over his love for, say, the Norse sagas that once moved the boy Lewis to tears, but may hear in them, with varying degrees of clarity, strains of unearthly music.

To become a poet and to become a Christian are not exactly two separate things. Poetry, insofar as it is true and beautiful, cannot of itself lead man to God, but it can serve as the bridge whereby man comes to knowledge of God.

Tolkien did not come up with that notion on his own. We find it in Dante. When the poets have reached the summit of the mountain, after all the purging and unfettering and healing and strengthening are accomplished, we find earthly Paradise, and a beautiful woman singing as she culls flowers from beside a clear and lovely stream. It is not Beatrice, not yet. The woman’s name is Matelda, and Dante gives to her, not to the heavenly Beatrice, the pleasure of revealing to the poets the nature of the place where she dwells—an earthly place, what was meant to be our place, most fit for innocent man before the Fall. And since she knows it is Statius and Virgil who accompany Dante here, she adds one last suggestion to what she has described. In doing so, she makes no distinction between Statius the Christian and Virgil the pagan; she treats both in their capacity as poets from the classical pagan past.

Though I’ll reveal no more, I will say this to satisfy your thirst— A corollary granted as a grace. It will, I think, be no less dear to you, for I will walk beyond my promises. The poets in their melodies of old may have dreamed on Parnassus of this spot, singing about the happy age of gold. For here the human race was innocent; forever spring, and fruit upon the vine. This is the nectar which the poets meant.”

And with that, though Matelda does not entirely commit herself to the possibility, Dante brings the best and wisest of the ancient pagan poetry into the drama of the fall of man and his redemption by Christ. If Lewis found a bridge to the faith in the myth of Balder the beautiful, the innocent Norse god who was slain by the cunning of the envious and malevolent Loki, and if Statius found a bridge in Virgil, who wrote that “the morning of humanity returns, / and a new age of justice has begun,” and if these bridges were not mere accidents but were what they were, in the grace of God, by the very nature of poetry at its most profound, then we too may find, in the honor we pay to human art, the same kind of enlargement of our hearts that God may enter and make his dwelling within us.

All of which brings me back to that evening in Princeton and to the worthy Scot who couldn’t write a lick of verse but who tried to do it anyway, and to the foolish young lady whose sins against truth and beauty and poetic form have paid off in much praise and money. No one in Professor Miner’s parlor would have dared to express scorn for the works of artists who preceded our own age. The academy had not yet been reduced to an arena for the politics of class, race, and gender. I suppose that most of us, at that time, had never read Virgil in the original Latin. I had not yet done so. William McGonagall, I am sure, never did so. But that was, in us, a failure in our education and not a deliberate aim. It was, so to speak, evidence of a bridge in disrepair, or neglected, not of a bridge blown up.

In general, I find that colleges have become places where young people go to become stupid in ways that unassisted nature could never have accomplished. A college education did not produce William McGonagall, but it did produce the young lady at the Biden inauguration. It is why, in most English departments, the study of such poets as George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, and Andrew Marvell is either reduced to contemporary politics or is tolerated as an exercise in the antiquarian. No one, in most of our schools, will read Herbert for his wisdom, or to learn the art of verse from him; at most of our schools, graduates in English will never have heard of the man whom I consider the greatest lyric poet in our language.

I wouldn’t have had a beer with William McGonagall, because he didn’t touch the stuff, and I wouldn’t have talked with him about poetry because he really didn’t touch that stuff either. But in other ways I think we’d have gotten along pretty well. As for scholars and poets in our midst who will have nothing to do with either Virgil or Dante, with the profoundly human that is oriented toward the divine, as all profoundly human things must be, as the mountain of Purgatory is, I do not know what we would have to talk about. And I am suspicious of the smell of char that hangs about them.

And there is what I see as central to any reform of education in our time. Just as we do not scorn the mountain of Purgatory because it is not heaven, so we do not scorn

human art, even pagan art, because it is not wrought directly by God’s own hand; nor do we scorn it, in our immense and incompetent pride, because it is old and does not wave the right political pompoms. For Dante treated the pagans with greater honor than we treat our own Christian and classical forebears.

God has, I believe, showered some measure of grace—though it may be great or small, and though the truth may be shrouded in mist—upon the work of artists who do somehow seek the good and who submit to learn from past masters of the art. Maybe sometimes this true art is like a rope bridge thrown over a canyon. But the rope bridge has this that distinguishes it from our contemporary gibberish: It goes somewhere.

Leave a Reply