“Likewise also the chief priests mocking said . . . Let Christ the King of Israel

descend now from the cross that we may see and believe.”

I have been a citizen of the sovereign state of California for most of my life. I can guarantee you, Alta California is not merely a result of the proverbial dreamin’, a state of mind, but an actual place. Its motto, which I reckon must thus be mine as well, loyal subject that I am, is Eureka, “I have found it.” Gold-bearing earth, as one might imagine, is the implied antecedent. Is the Golden State really not just a state, but a natural place, a destination, or even a destiny? Is this motto a statement or—niceties of Greek particles aside—a question? Have I found in this place my true home? Is this a real inventio loci, not merely rhetorical art, but natural necessity?

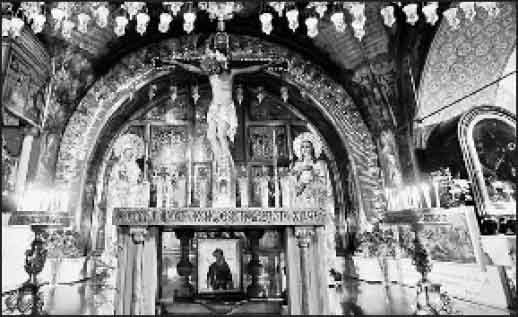

“We have found Eden.” Eurekamen Edem. So reads the monogram at the foot of the Calvary depicted on the full scapular of the great habit of the Orthodox monastic. Eden is, of course, the terrestrial paradise, not the celestial one. A monastery, a place of self-denial and ascetic struggle, hardly suggests a place of delight. Then, perhaps, such an exclamation should be taken allegorically as meaning Heaven, or beatitude, or salvation, rather than the very corporeal garden of immortality and incorruption. Yet the Calvary this motto inscribes is undoubtedly a physical place as well as a spiritual archetype. Might the Christian agonistes pneumatikos have found an Eden which is a concrete physical place as well? To speak as a medieval schoolman (or, to be fair, as Isidore of Seville and Gregory of Nyssa much earlier), does he, in fact, dwell in his Eden as a natural place—that is, as an extended body materially contained and resting in a quantity formally fixed in relation to the center of the earth?

Now, let us set aside any sophisticated tendencies we might have acquired from professional educators to deconstruct the ideal Christian’s claim to have found Eden in terms of the “nonlocal universe” we are supposed to inhabit, one that has become less and less a topographical reality since Galileo and is not even a graphical one since Einstein. Paradise, Heaven, Hell, and, as your doctrine permits, Limbo and Purgatory, have been for some time conceived as mere states rather than as places, and so it is small wonder that now not even the physical universe is to be understood as located or locating. Perhaps soon those who hold that there is any such thing as a place at all will join the ranks of naive “fundamentalists.”

Yet, for ancient and medieval minds, there was simply no question that Earth, Heaven, and Hell were places in the corporeal sense and that their locations were known, even if the latter two were ordinarily unreachable. Purgatory was a place as well, although there was some little speculation as to its location. Man’s present and ultimate places were not a matter of dispute; rather, it was the bodily, local reality of the original place of Man that engendered a formal theological question. In his Commentary on the Sentences, and in his Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas, for example, never poses the question of whether Heaven, Hell, or Purgatory are places, but in the Summa, he does pose the question regarding Eden: “On the place of Man, which is Paradise: whether Paradise is a bodily place.” The question comes up, on examining the objections given, primarily from a scientific point of view. Quite simply, no one has ever found this place on Earth, for its four rivers and other characteristics do not match any known place even to those who have “most diligently” sought it out. But a place it is, Saint Thomas asserts, located in “the East,” but perhaps it cannot be found by reason of the cherubic ministry which prevents its discovery. Enoch and Elijah are there, in expectation of their return to their postlapsarian places at the end of the world, as described in the book of Revelation.

Yet, even so, this Californian Christian dares to cry out with anyone else who cares to join him, both to those who say there is no such place and to those who say it cannot be found: Eureka, “We have found Eden.” Where? Let me explain. The ancient notion of natural place, in its sheerest formality, prescinding from the outmoded cosmology with which it is unnecessarily associated, means simply this: Each bodily thing has a natural tendency, all things being equal, to rest in the bodily context that best favors its conservation and formation in being. Thomas Aquinas explains that, since the first man was immortal in body by a divine gift and not simply by nature, Adam was made from the earth outside of paradise, and then, as Genesis relates, God placed him in the Garden, which was the natural place fit for the habitation of an immortal man, with the external climate and location that favor human health supplementing the internal power of immortality given to his soul. There, Eve was made, and their children (alas for us!) would have been born according to the normal way of human generation (less often, yet with greater pleasure, the Angelic—but still humane—Doctor points out), but without the corruption of death, until they should be translated, body and soul, to the empyrean heaven. Outside the Garden, the rest of the Earth was created as it is now, a place of generation and corruption, of birth and of death.

It is in this world that human societies must now be set up. On examining Aquinas’ little treatise De Regno, written for the Lusignan crusader king of Cyprus, one finds that it is with the original paradisiacal state of fallen man in mind that he describes the work of a king. The king must take the Creator as the model of government in founding and ruling the state. Thus, his first concern is the spiritual goodness of his people, expressed in worship, ordered to the life of immortality, the heavenly goods offered by the Christian priesthood. The king’s next concern is the proper place of his city, which must have qualities conducive to human procreation and longevity, a climate like that described for Eden, while taking fallen nature into account:

The founder of a city and kingdom must first choose a suitable place which will preserve the inhabitants by its healthfulness, provide the necessities of life by it fruitfulness, please them with its beauty, and render them safe from their enemies by its natural protection . . . A spot where life is pleasant will not be easily abandoned nor will men commonly be ready to flock to unpleasant places, since the life of man cannot endure without enjoyment. It belongs to the beauty of a place that it have a broad expanse of meadows, an abundant forest growth, mountains to be seen close at hand, pleasant groves and a copiousness of water . . . There is another means of judging the healthfulness of a place . . . the presence of many and vivacious children, and of many old people.

By the above standard of kingly government, this much is clear: Our rulers have not been taking care of us, lo these many years, not since our revolution, or anyone else’s. In our day, Thomas would not have written De Regno for the king of Cyprus but an exegesis of Psalm 146 (145):3 for, let us say, the editor of Chronicles. “Nolite confidere in principibus.” (“O put not your trust in princes.”) Now, most us of live in a place based on whether we can make a living there, since our society, unlike the one described and praised by Aquinas, is based on commerce. And, as thousands of invisibly but politely nodding subcontinental tax experts will tell you, it barely matters where you live anymore. In spite of the Mediterranean (Californian?) ambiance presented as an ideal, it is now a necessary place only for those who come to pick grapes and strawberries at piece rate. We have, after all, modern technology and medicine to guarantee our comfort and longevity anywhere, and, as for procreation, well . . .

Exactly. Procreation is the key to understanding how we have, or can find, Eden, since we have no Christian princes in whom to trust. The ancient blessing over the newlywed spouses in the Roman Missal tells us that the procreative union of man and woman in marriage is the one and only blessing not taken away by the punishment for original sin: quae sola nec per originalis peccati poenam nec per diluvii est ablata sententiam. Now, if this blessing was not taken away, it must be, like the medicinal penalties, a means of repairing the damage done, a means of redemption. Those words of the nuptial blessing are spoken by the priest after the Lord’s Prayer, when the Body and Blood of Christ are lying on the altar as a memorial of His sacrifice on Calvary, the sacrifice of the New Adam, the Bridegroom of our fallen race. Calvary and procreation: two remedies for the expulsion from Eden. Little wonder that, in Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the chapel of Golgotha is called the “Chapel of Adam” and that right by it is the marble mound called by the ancient cartographers the omphalos, the navel of the world.

Under the cross on the scapular of the Orthodox monk’s great habit is found another monogram inscription bearing the sentence “The place of the skull has become Paradise.” Christ suffered outside the city in the place where Adam’s fallen children were buried. It is He Who cried, “And if I be lifted up from the earth I will draw all things to myself.” His Cross is the natural place of regeneration, and the fallen world of which the Cross is the true center is as natural a place as was Eden for its one prelapsarian blessing: the begetting of children.

It is this blessing the monk forgoes, like Christ Himself, not finding a place to lay his head, in order to point the way to Heaven. Since the world began to drive out the vigilant monks from their crucified gardens, it has been preparing for a second fall, one which, unlike the first, is irreparable because it rejects the only blessing left: marriage and family. Soon families, too, may find themselves relegated to the savage reserves of a Brave New World. But then, with the monks, they will be the only real places left in the “nonlocal universe.” There, bodies and souls will still be born and die and rise.

Life in a well-ordered society, one that is really our place because it conserves and forms our lives for the good, is no more or even less of an historical possibility for us today than to gain re-entry into the earthly paradise. We are truly more than ever “displaced persons,” not having here a lasting city. If we gather our wives and little ones around the altar of the Cross and Its chaste ministers, however, we retain the only blessings not threatened by the second fall and the second death. Even as we live in California, or in any other state, we shall find our natural place in an Eden as real as our bodies—and as His Body—until we are drawn to an even better place. Yet, I warn you, this will come about only when families have had to join the mocked procession described by the unmonastic Milton, who was more worldly than he knew:

. . . Then might you see

Cowls, hoods, habits, with their wearers tossed

And fluttered into rags . . .

The sport of winds. All these upwhirled aloft,

Fly o’er the backside of the world far-off,

Into a Limbo large and broad, since called

The paradise of fools.

“California, here I come.”

Leave a Reply