Despite the President’s and Congress’s promises, the budget is unlikely to be balanced in the year 2002. The bulk of the promised spending cuts come after the year 2000, and future Congresses and Presidents are unlikely to be any more willing than present ones to make tough political decisions.

Equally problematic is the fact that both parties continue to protect large segments of the budget, like defense, from serious reductions. Over the next five years, military expenditures will fall, but only in real terms, as budget increases are held below inflation. Even this “cut” was approved only grudgingly, as both parties have competed to restore previous reductions.

However, military outlays should be an obvious target for budget-cutters in the coming years. Defense spending does not exist in a vacuum; it is the price of our foreign policy. When the United States faced the threat of hegemonic communism—an aggressive Soviet Union aided by client states worldwide—it chose the policy of containment, which required a large military, numerous alliances, scores of bases, and an advanced force presence around the globe. All told, Washington spent more than $13 trillion (in today’s dollars) to win the Cold War.

But in 1989, all the assumptions underlying American foreign policy collapsed. The Central and Eastern European states overthrew communism, the Berlin Wall fell, the Warsaw Pact dissolved, and the Soviet Union disappeared. A military strategy and force structure designed to deter Soviet aggression was suddenly obsolete; the United States faced no adversary worthy of the name.

Military spending did not change accordingly, however. True, outlays have fallen, but only from the 1985 peak, up 55 percent from 1980, caused by the Reagan defense buildup. At roughly $270 billion, military outlays in 1997 remained above the level of 1980, even in inflation-adjusted terms. Indeed, President Clinton is spending more than Richard Nixon spent in 1975 and almost as much as Lyndon Johnson spent in 1965 during the height of the Cold War. Outlays are running at 85 percent of the Cold War average, without a Cold War. Washington accounts for a larger share of the globe’s military expenditures today than it did a decade ago, when it faced a hostile hegemonic threat.

But this is not enough for many policymakers. Conservatives led by Republican pundit William Kristol, former drug czar William Bennett, Family Research Council President Gary Bauer, potential presidential candidates Steve Forbes and Dan Quayle, and neoconservative journalist Norman Podhoretz have formed the Project for the New American Century. The organization is dedicated to promoting what Kristol characterizes as “benevolent hegemony.” As he argues, “we need to increase defense spending significantly if we are to carry out our global responsibilities,” namely, imposing order around the globe. Kristol advocates an annual increase of $60 to $80 billion. Groups like the Heritage Foundation are only slightly less extreme; the latter proposes a hike of $20 to $25 billion a year. House Speaker Newt Gingrich has proposed no specific number, but recently urged the Budget Committee to increase the military’s budget significantly. According to Gingrich, “We have lived off the Reagan buildup about as long as we can. The fact is that our defense structure is getting weaker, our equipment is getting obsolete, and our troops are stretched too thin.” Similarly, National Review calls for “reversing the decline in our defense budget.”

President Clinton, as is his wont, has arrayed himself as a pale version of his critics. Last year he asked Congress to hike military spending. The administration boasted that for “the fifth time in four years . . . the President increased defense spending above previously planned levels.” Not surprisingly, one anonymous Pentagon official told the New York Times that “the Defense Department has fared well in the budget deliberations.”

The Pentagon recently finished its quadrennial defense review. Naturally, the Department advocated the warmed-over status quo. Defense Secretary William Cohen proposed preserving the current force structure, slightly paring manpower levels, and allowing inflation slowly to erode overall expenditures. He envisions no change in strategy, with the Defense Department remaining committed to fighting two wars almost simultaneously. It is as if the Cold War never ended.

There is little serious partisan disagreement on this score. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright has been consciously building GOP support for administration policies. As she puts it, “Both parties are led by people who understand the importance of American leadership.” The administration even considered enlisting former Republican presidential nominee Robert Dole to promote its plans for NATO expansion and an extended stay in the Balkans.

What is the justification for a potentially huge military buildup? Some advocates contend that America is in danger of becoming a second-rate military power vulnerable to attack. Marine Commandant Charles Krulak speaks of a continuing “national demobilization.” During his campaign. Dole warned that “peace is threatened and dark forces are multiplying in almost every corner of the globe. All of us have seen how an enemy can rise suddenly and strike quickly when America seems unprepared.” Columnist Harry Summers argues that if the United States does not have “military forces deployed around the world,” Americans will find the enemy “at our throats.” The Pentagon’s two-war strategy, explains Secretary Cohen, “signals our resolve to friends and foes alike.”

Where, however, are these foes? Today the United States dominates the globe, accounting for over a third of its military outlays. Washington presides virtually without enemies. America and its friends account for about 80 percent of the world’s military spending. States with civil (if at times uncomfortable) relations with the United States, particularly China and Russia, account for the bulk of the rest. Even former Defense Department official Zalmay Khalilzad admits: “the U.S. is without peer. We face no global rival or a significant hostile alliance. Indeed, the world’s most powerful and developed countries are our friends and allies. In modern times, no single nation has held such a predominant position as the United States does at present.”

Yet in a world so very different from that of the Cold War, Washington spends even more compared to its allies and potential adversaries than before. American military outlays are more than thrice those of Moscow, nearly twice those of Britain, France, Germany, and Japan combined, and eight times those of China. As a share of Gross Domestic Product, American military expenditures are four times those of Japan, and two or more times those of most of its European allies. American citizens spend more to defend South Korea than do the South Koreans. America’s interests in the world are great, but the United States does not have more at stake in Europe than do the Europeans, or have a greater interest in the independence of South Korea than do the South Koreans. There is something very wrong with this picture.

Of course, as House National Security Committee Chairman Floyd Spence observes, “It’s still a dangerous world.” It is not particularly dangerous for America, however. As Colin Powell noted when he was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “I’m running out of demons. . . . I’m down to Castro and Kim II Sung.” The impoverished communist dictatorships of Cuba and North Korea may be ugly, but neither threatens American security. The mere fact that a conflict may break out somewhere in the world does not mean that it would be in Washington’s interest to intervene, or that America’s friends could not look after themselves.

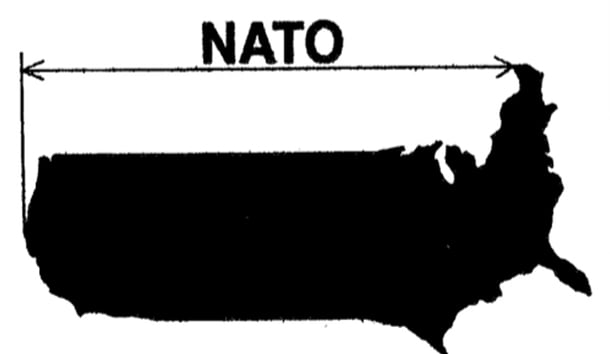

The largest component of the Pentagon budget is devoted to traditional alliances such as NATO. In Europe, 100,000 American soldiers stand guard lest phantom Soviet divisions roll West. While the future direction of Russia remains unclear, the Western Europeans, with a combined population of 414 million and GDP of $7.4 trillion compared to 149 million and $1.1 trillion, respectively, for Moscow, are eminently capable of defending themselves. Britain and France possess an independent nuclear deterrent. Together they, along with Germany, spend 25 percent more on the military than does Russia, which has just announced a further cut in defense outlays. It is time for the Europeans to take over NATO.

American-backed expansion into Central Europe makes even less sense than continued support for the Western Europeans. While the former communist satellites should be integrated into the West, the best means to do so is economically through the European Union. These struggling nations need access to Western markets, not the presence of Western soldiers. Yet the Western Europeans continue to dawdle, preferring to offer American military subsidies rather than risk increased European economic competition.

Moreover, America has no vital interest that warrants guaranteeing the borders of Poland, Hungary, Rumania, the Baltic states, Ukraine, and whoever else ends up on a NATO wish list. These nations obviously matter more to Western Europe, and that means Western Europe should defend them. The Western European Union, EuroCorps, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and even an America-less NATO all provide potential frameworks for a European organized, -funded, and -manned defense of the East.

But lack of national interest is obviously no bar to American military intervention. Although Europe looks secure, NATO officials peer south as well as east, and see only trouble. Many alliance planners say that the greatest risks of conflict lie south of Europe. Explains Adm. T. Joseph Lopez, commander of NATO’s Southern Command (AFSOUTH): “The next war could grow out of any number of explosive factors—economic difficulties, water shortages, religious fanaticism, immigration, you name it. There are many different forces of instability in the southern region.” Naturally, he believes Washington must intervene, explaining that “I can think of no foreign theater more critical for the United States. We have to stay engaged, with a robust force and the political will to use it.” Indeed, he advocates “engagement across the line,” since that strategy is what won the Cold War, Of course, acknowledges Lopez, “instability is a difficult enemy to deal with.”

Well, yes, as Washington is discovering in Bosnia. The United States is already deeply enmeshed in the Balkans, a region with no serious link to American security. Despite the ongoing Western occupation, there is little support among any of the three hate-filled ethnic groups for preserving the artificial Bosnian state, a Utopian goal of no practical value to America or even Europe. Nevertheless, Washington is now using its military to support one nationalist politician over another in Serbian Bosnia. It turns out that the kind of democracy Washington is intent on bringing to the Balkans—by seizing television and radio stations when it disapproves of their broadcasts and transferring control of police stations to factions it views as more pliant—is more representative of Boss Tweed than George Washington. But good policy does not seem to be the goal. As the Weekly Standard explains: “We need to make it clear, not just to Bosnians but to the world, that it’s much safer to be our friend than our enemy.” Perhaps we should just begin bombing.

These sort of arguments about U.S. leadership, routinely made by advocates of a Pax Americana, are just plain silly. Leadership requires acting even when those on whose behalf one claims to be acting do not think the issue is important enough to act? That is the conduct of a sucker, not a leader. And what foes and what commitments are at stake? If Washington does not try to rebuild a Muslim-dominated Bosnia, then what? Would China attack Taiwan, North Korea attack South Korea, Russia invade Germany? It would have been an exercise in real leadership to ignore the Europeans’ attempt at blackmail—threatening to remove their forces if President Clinton had tried to fulfill his original commitment to bring American troops home by July. He should have kept his promise, telling the Europeans to do as they wish.

But meddling in Bosnia is not enough. Violent unrest in Kosovo, a Yugoslav province largely populated by ethnic Albanians, has generated calls for intervention. The United States is “not going to stand by and watch” Yugoslavia crush political freedom in Kosovo, thundered Secretary’ of State Albright. Albright pushed for economic sanctions and an arms embargo. She is a moderate, however. The Balkan Institute proposes “threatening U.S. military intervention to halt provocative violence by Belgrade.” Janusz Bugajski of the Center for Strategic and International Studies advocates declaring the province to be a NATO protectorate and launching air strikes against Yugoslav military targets.

Certainly, one can argue that Yugoslavia should provide political rights to Albanians in Kosovo. But it is a dictatorship that does not give full political rights to Serbs. In any event, the issue is not humanitarian. Washington cares not one whit about ethnic self-determination when it come to Serbs dominated by Croats and Muslims, or Kurds brutalized bv Turks.

Unfortunately, Bosnia is only the start, at least if current Washington policymakers have their way. Adm. Lopez says, “If you take a macro-look at our theater, it’s literally filled with instability and pockets of unrest.” Examples include Albania, Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey, Libya, the Middle East, Syria, and Zaire. “With the end of the Cold War, the new enemy is instability, and it is manifested in this region more than in any other place in the world,” Lopez argues. “Our business and our mission is to maintain stability.”

This is apparently why the United States has been aiding the militaries of Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, areas never before thought to be of great strategic interest. Washington has been providing military aid to Uzbekistan; it has also established the United States-Uzbekistan Joint Commission to study military and political cooperation.

Moreover, in 1996 the United States conducted military exercises in the region. Explained Marine Gen. Jack Sheehan, commander of the U.S. Atlantic Command, if the U.N. ever authorizes a “peace support operation”—whatever that is—in the Central Asian nations, “then the United States is ready to stand beside them and participate.” To this cheery thought, he added: “There is no nation on the face of the earth that we cannot get to.” He did not explain, however, why the United States would want to get to such distant, impoverished nations, which border on Afghanistan, China, and Russia.

AFSOUTH is also advocating a “Mediterranean Initiative” that promotes military contacts with Egypt, Jordan, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. But Adm. Lopez wants more, much more — to expand the so-called Partnership for Peace, the precursor to NATO expansion into Central Europe, to such nations. And the Sixth Fleet has been conducting training exercises throughout West Africa. “I believe there’s a need to make new friends,” says Lopez, “so that NATO and the United States are viewed in a positive, rather than threatening, way.” In other words, NATO will become a big Peace Corps, only with nuclear weapons.

Is there no country over which America is unwilling to go to war? The answer, unfortunately, appears to be no. NATO officials suggest that “out-of-area” actions may become the alliance’s primary focus in the future. For what conceivable purpose? Capt. Ken Golden, commander of an Amphibious Readiness Group attached to the Sixth Fleet, says “While a lot of Americans back home seem to think we don’t have enemies anymore, I can tell you there’s a lot of hatred out there. The world as we see it out here is a very unsettling and unstable place.” Yes, but our enemies—such as Cuba and North Korea—are simply pathetic. And most of the hatred would not be directed at the United States if Washington did not meddle in all sorts of faraway, irrelevant conflicts.

The case for maintaining 100,000 soldiers in East Asia is equally dubious. South Korea has 24 times the GDP and twice the population of North Korea. The former is a dominant trading nation, produces a wealth of hi-tech products, and has stolen away almost all of its adversaries’ allies. The latter is impoverished, isolated, and incapable of feeding itself. It is as if the United States were dependent on outside support to deter Mexican aggression.

Similarly, a military presence imposed on Japan when it was a distrusted and war-torn former military dictatorship remains today, even though Japan is now the second-ranking economic power on earth and has peacefully attained most of its World War II goal of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. It was one thing to borrow money from Japan to defend Japan when Tokyo faced a potentially aggressive Soviet Union and was incapable of defending itself. It is quite another to do so when the threats against Japan have greatly diminished and Tokyo’s defense capabilities have greatly increased.

And no replacement threats loom on the horizon. China is growing, but it seems assertive rather than aggressive, and its military expansion has so far been minor. Japan and the other East Asian states are capable of maintaining a sufficient military deterrent, and that will not change for many years. China remains poor and underdeveloped despite its recent explosive economic growth.

Germany and Japan are still feared by some neighbors, but neither has a double dose of original sin, and both are unlikely to attack powerful neighbors, many of whom possess nuclear weapons. Brazil, India, and other nations may eventually evolve into regional powers, but the United States has no reason to treat them as enemies and plenty of time to respond if they become hostile. Outlaw states like Iraq and North Korea pose local conventional threats that should be contained by their neighbors, not the United States. The problem of nuclear proliferation is more complex, but not easily resolvable through conventional military means by Washington.

The administration found this to be the case with Iraq. The President was never able to articulate a serious purpose for a winter war in the Gulf Defense Secretary William Cohen, who promised “substantial” strikes, admitted that they would neither drive Saddam Hussein from power nor stop his attempt to create weapons of mass destruction. They might not even have caused Hussein to agree to further inspections. And yet the United States remains prepared, should Hussein again resist U.N. authority, to risk military action, kill innocent civilians, foul relations with allied states, and inflame potential terrorists.

The Hussein regime is one of the more ugly to dot the globe, but it is hardly alone. It is not even the only unpleasant dictatorship attempting to build biological, chemical, or nuclear weapons. Every time the United States threatens such regimes with war, it only strengthens their desire for such weapons to deter future American military action.

While Iraq has no capacity to respond militarily, sober Washington policymakers should realize that the United States remains at risk to terrorism which, as the bombing of the World Trade Center demonstrated, is the poor man’s form of retaliation. Washington needs to negotiate an end to sanctions on Iraq and, along with allied states, rely on normal military means to deter Iraqi use of any weapons that it might acquire. America obviously faces no danger, while Israel already possesses an adequate deterrent. And the Gulf states, if they feel threatened, can cooperate with such nations as Turkey, and build militaries capable of doing more than arresting domestic critics.

The globe remains an uncertain place, and new threats could arise over the long-term. But that does not require Washington to attempt to micromanage a world that will always be unsettled. Secretary of State Albright says of her interventionist views: “My mind-set is Munich.” There was only one Hitler, however, and Europe’s circumstances during the 1930’s were unique. Thus, the United States need not confront militarily every nation with which it has a disagreement. Rather, Washington should remain wary and watchful, prepared to play the role of distant balancer should a potential hegemonic threat arise that cannot be contained by friendly states. America will be better able to meet genuine future threats if it does not exhaust itself attempting to maintain an hegemony, benevolent or not, that is sure to be resisted by many friends as well as foes.

Another mission is trying to rebuild failed societies, which could also absorb significant military forces. In tact, it already has. As John Hillen, a Fellow for National Security at the Council on Foreign Relations, puts it, “the United States has had difficulty saving no to almost any call for military action in the past five years,” undertaking some 50 different military missions all over the world. And there could be even more demands for American intervention in the future. Today some 30 Third World brushfires are raging. National Security Advisor Sandy Berger talks of using American power as “the decisive force for peace in the world.” Senator Richard Lugar, one of the GOP’s leading foreign policy spokesmen, argues that “we have an unparalleled opportunity to manage the world.”

But Somalia vividly demonstrated how difficult it is for officials in Washington to reach inside and manipulate other societies, let alone to resolve ancient hatreds and political divisions. America’s military pressure helped halt the fighting in the Balkans, but only after allowing the very partition that Washington had long resisted. Moreover, American involvement has simply suppressed regional antagonisms, not resolved them.

Nor is there any reason to try to fix broken states. That tragedy abounds in a world so full of opportunity is perhaps the great anomaly of our age. But failing to recognize the inherent limitation on the ability of Washington to “manage” other countries ensures that officials will only compound the tragedy elsewhere by sacrificing the lives of Americans as well.

Of course, some analysts seem unconcerned about the prospect of risking the lives of American servicemen for any number of dubious purposes. Then-U.N. Ambassador Albright asked Colin Powell, “What’s the point in having this superb military that you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?” That’s easy to say if one doesn’t have any family members or friends in tire military. But as Powell retorted, GIs are “not toy soldiers to be moved around on some kind of global game board.” The American people obviously agree, given their reaction to the disaster in Somalia. This has led to criticism by some foreign policy elites. Writes Thomas Friedman of the New York Times, “We can’t lead if we don’t put our own people at risk.” But real leadership does not mean sacrificing soldiers’ lives for interests irrelevant to their own political community.

Even in distant wars with some plausible security implications, like the Balkans, other nations, in this ease those of Europe, have far more at stake than does the United States. Moreover, non-intervention offers the surest method to contain such conflicts. Alliances proved to be transmission belts of war in World War I, drawing ever more peripheral powers into a conflict that proved disastrous for every one of them, hi contrast, the same nations erected firebreaks to war when fighting broke out in Yugoslavia in 1991. Thus, the conflict burned longer than World War I without spreading.

The final refuge of those who support big military budgets is “leadership.” Republican presidential nominee Bob Dole made that undefined term his 1996 campaign mantra. Vice President Al Gore matched Dole by telling the 1996 Veterans of Foreign Wars convention that “America must act and lead.” House Speaker Newt Gingrich makes much the same pitch: “You do not need today’s defense budget to defend the United States. You need today’s defense budget to lead the world.” Secretary of State Madeleine Albright says that America must “accept responsibility and lead.” William Kristol’s Project for the New American Century proclaims: “We cannot safely avoid the responsibilities of global leadership.”

There is virtually no limit to the responsibilities entailed by this popular goal. “At times,” declares Joshua Muravchik of the American Enterprise Institute, the United States “must be the policeman or head of the posse—at others, the mediator, teacher, or benefactor. In short, America must accept the role of world leader.” Zalmay Khalilzad cites as responsibilities of leadership preparing for such contingencies as tension in the Balkans, a China-Taiwan confrontation, and “an internal conflict in a key regional state,” presumably meaning involvement in a civil war. This attitude even leads to support for intervention simply to demonstrate leadership. Former Secretary of State Warren Christopher called Bosnia “an acid test of American leadership,” Having gotten involved, the United States naturally cannot leave without fulfilling its goals—in order to demonstrate leadership. Richard Holbrooke, who negotiated the unrealistic agreement for an artificial, polyglot Bosnian state, declares that “failure is unthinkable. We cannot afford to fail.”

However, the United States has the largest and most productive economy on earth. It is the leading trading nation. The American constitutional system has proved to be one of the world’s more durable. American culture—like it or not—permeates the globe. An oversized military is not required for “leadership.”

Anyway, even significant budget cuts would leave Washington with the world’s largest and most advanced military, far stronger than that of any other state or coalition of states. And those cuts would allow the economy, America’s most important source of influence, to grow faster. Today, Washington’s disproportionate military burden does more than divert precious economic resources down wasteful channels. It simultaneously relieves America’s industrialized competitors from spending more on their militaries. This has allowed Japan and Europe, in particular, to gain an edge they otherwise would not have. Not surprisingly, such international dependents want to keep their generous U.S. subsidies: both Germany’s Helmut Kohl and France’s Jacques Chirac have shamelessly demanded a continued American military presence in Europe while cutting back on their own defense.

There are alternatives to America’s unilateral hegemony. In some areas, regional security organizations, like the Western European Union or an America-less NATO in Europe, could keep the peace. Another option is informal spheres of influence, where interested local powers help maintain stability in their own regions — essentially America’s strategy in Central America. Finally, a rough balance of power may generally constrain potentially aggressive powers; such a system could evolve in both East Asia and the Middle East if the United States reduced its dominant presence.

No one wants America to be weak or vulnerable to potential enemies, which is why defense spending on training and technology should remain priorities. This is also why policymakers should beware turning the military into something else, either through social experimentation, such as the feminization of training and standards, or involvement in humanitarian missions. Of the latter, warns a recent Foreign Policy Research Institute task force, “U.S. forces engage in the politics, ambiguities and complexities of ‘peacefighting,’ often at the expense of their ‘war-fighting’ skills and training.”

In fact, the Pentagon has expressed concern about a deterioration in individual aggressiveness, fighting skills, and weapons maintenance after interventions like Somalia and Haiti. Repeated military deployments for strategic marginalia have also lowered morale and cut retention. As a result, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff John Shalikashvilli worries that American forces “will take more casualties” in a real war, the sort of serious contingency which the military was originally established to meet.

We need to match forces to missions, and to do so we must reconsider strategies made obsolete by a changing world. Zalmay Khalilzad worries that the collapse of the Soviet Union, “the common enemy that helped bring” America’s disparate alliances together, creates the danger “that these alliances will weaken and eventually collapse.” But the disappearance of the threat that animated such military organizations should lead to their disappearance, at least as originally formed. The United States should adjust its force structure for a post-Cold War world by shifting defense responsibilities onto allies and eliminating units currently dedicated to those tasks. Doing so would allow a radical restructuring—from, for instance, 1.5 million to 900,000 servicemen, 12 to 6 aircraft carrier battle groups, 20 to 10 Air Force tactical air wings, and 10 to 6 Army divisions. The military budget could be cut to some $170 billion, down from nearly $270 billion today.

Congress would even find a political benefit in doing so. Medicare and Social Security costs will explode during the next decade: Congress will have to choose between subsidies for America’s elderly and subsidies for foreign allies. And there is no doubt where the public stands. Although Joshua Muravchik complains that the media “has given the American people a very distorted picture of our military effort” by suggesting that defense outlays are too high, it is really the politicians seeking higher military outlays who are misleading the American people. Polls find rising support for sizable cuts in military outlays when voters find out how much the United States actually spends compared to its allies and potential adversaries.

The federal budget will never be balanced unless Congress and the President make some tough choices, including cutting military outlays. Washington spends far more than is necessary to protect America and its vital interests around the world. In the absence of a threatening global hegemon, the United States should again become a normal nation, with a normal military.

Leave a Reply