All societies regulate personal behavior: That is part of what makes them societies, instead of mere aggregations of isolated individuals. Societies differ enormously, though, in just how they perform this regulation, how much they rely on law and the state, rather than informal or private means. If I walk into a crowded room wearing a Cat-in-the-Hat hat, people will laugh, since laughter is a powerful means of social sanction, an informal way of telling me my actions are deviant. If I am wearing nothing but said hat, people may still laugh, but additional sanctions will be imposed in the form of arrest, trial, and criminal punishment. All societies have extreme sanctions that they can levy against personal behavior that is seen as threatening. What has been unusual in recent years about the United States, and many of its European clones, is the tendency to extend official public sanctions to activities that, not too long ago, were viewed as private. Instead of unofficial sanctions (such as saying, “Did you hear what he did? What a jerk“), we move all too quickly to the realm of law, where the merely obnoxious and offensive becomes criminal. As American criminologist Raymond B. Fosdick lamented back in 1920, “We are of all people, not excepting the Germans, pre-eminently addicted to the habit of standardizing by law, the lives and morals of our citizens. . . . We like to pass laws compelling the individual to do what we think he ought to do for his own good.” If anything, the addiction has grown worse since Fosdick’s time, with the expansion of criminal law to regulate interracial relations, sexual harassment, even smoking. As the realm that was once subject only to good manners shrinks, the state happily expands to fill the void, usually with announced goals that sound just wonderful: Who would say a word against tolerance and social harmony, the legislation of civility?

In most Western societies, historically, the official criminal law covers a far smaller area of life than most of us realize. Before the rise of formal police systems in the 18th and 19th centuries, a huge amount of interpersonal behavior was regulated by quite elaborate community-based mechanisms that did not invoke the assistance of courts or the state. Since these informal mechanisms by definition were not recorded in elaborately filed documents, historians generally know little about them and, therefore, write as if they did not exist. But literary evidence tells us of events like the “love-days” that were commonplace in medieval and early-modern England, when communities would gather periodically to resolve rows, feuds, and disputes, dealing with matters as serious as murder and abduction. In some European societies, the Church organized special ceremonies to reconcile rivals, to make them swear to abjure violence in the future, and even promise to love each other. On a somewhat comical note, when modern historian John Boswell found puzzling records of these rituals, he believed that he had found the liturgies of Church-approved same-sex unions, or gay marriages, and he wrote a much-discussed book presenting this utterly wrongheaded view. In reality, the Church was just consecrating something the community thought its proper role, namely, maintaining social peace between people and families without involving kings, judges, or lawyers.

Love-days were long-forgotten by the 19th and 20th centuries, but for most of that period, the law had nothing like the expansive ambitions that it has today. Of course, the community still regulated what people could say and do, but generally, it did so by informal customs, the network of boundaries and sanctions that we can loosely call “manners.” Now, to talk about the manners and proprieties of bygone ages is to suggest an elaborate charade of hypocrisy designed to provide a deceptive veneer to a society founded upon brutality and exploitation: insisting that people choose the correct fork for dinner while people were being lynched outside. A good case can be made, though, that appeals to manners had at least as much of an effect as law in improving people’s lives, in extending their life chances. I think, for instance, of Mark Twain’s commentary on the Chinese of California and the American West in Roughing It, where his most powerful argument for treating this “kindly disposed, well-meaning race” with the respect and decency they deserved is that this behavior is an essential part of good manners. The Chinese, he wrote, “are respected and well treated by the upper classes, all over the Pacific coast. No Californian gentleman or lady ever abuses or oppresses a Chinaman, under any circumstances, an explanation that seems to be much needed in the East. Only the scum of the population do it—they and their children.” Manners mattered, manners shaped behavior, and the sense that you were behaving like a gentleman or lady was a potent sanction against wrongdoing. As in this instance, a sense of civility and manners helped begin the eradication of casual racism in American life: As Twain was asking his compatriots, do you really want to act like scum?

This notion of civility may seem like a luxury for a tiny elite of the well-to-do, but we should never underestimate the enormous power of social emulation, the desire to act like your social betters. Between the mid-19th and mid-20th century, the spread of these ideas of manners, the ideology of a gentleman or lady, had an incalculable effect in the civilizing of American society, long before the law could do anything in this regard. In no particular order of priority, these notions of civility and good behavior assured that lynching was confined to the extreme backwoods and byways of America. They transformed ideas of appropriate sexual behavior and spread the notion that a man who beat or demeaned his wife was a brute unfit for civilized company, as was a persistent wolf, groper, or lecher. Ideals of civility helped to transform American interpersonal conflicts, minimizing such traditional horrors as the knife-fight and the eye-gouging contest. They taught generations of Americans that, while being drunk occasionally was acceptable, the proper behavior in this condition was humorous stupidity, not boorish aggression, much less violence directed against the weak. A social revolution in American life had been accomplished long before World War II, without benefit of law.

It is useful to stress all this in view of the currently popular view of what the American past was like before the blessings of sexual-harassment law, hate-crime protections, and other recent legal panaceas. I am exaggerating somewhat, of course, but most of our college students seem to imagine the America of the 1950’s as an age of daily lynchings, a time when no woman was safe from casual rape and the nighttime streets were lit by the carcasses of burning homosexuals and communists. I am not exaggerating when I point out that most Northerners confidently believe that the word “nigger” was freely used by all residents of Southern states before 1970 or even later. They refuse to believe that it had been many years since anyone with the slightest pretensions to decency, civility, or manners would have used such a word. To adapt Twain’s Roughing It once more, the word was the preserve of the scum, “they, and, naturally and consistently, the policemen and politicians, likewise, for these are the dust-licking pimps and slaves of the scum, there as well as elsewhere in America.”

To understand the process of historical falsification so busily at work in our textbooks and in the popular media, we must appreciate how emerging interest groups project their ideas in a society like ours. Primarily, they must show that there is a grievance that cannot be accommodated within the existing society and which, therefore, requires some kind of legislative change to serve as a landmark of the group’s success. In order to justify this legislation, it has to be shown that the state needs to intervene to achieve those things that could not be done by manners alone, by the natural evolution of standards within culture and community. The past must thus be painted in the grimmest possible terms, ignoring or understating the real progress that had occurred and was occurring. Once legislation passes, it has a natural tendency toward “legislation creep,” the expansion of law into matters once regulated by informal controls. There is no law so well written that it cannot be stretched beyond the bounds of absurdity, and laws designed to order people how to live together in civility arc anything but well written.

Sexual-harassment legislation offers a classic example here. During the 1970’s, the emerging feminist movement made rape one of its central themes, an issue as momentous as lynching was for civil-rights groups. Once rape legislation was changed across the country, new areas of concern had to be identified, and this meant the discovery of both child sexual abuse and sexual harassment. Harassment was a particularly tempting target in an age when millions more women were entering the workplace and struggling to define appropriate boundaries with male colleagues. Everyone agreed, moreover, that harassment was wrong, at least in the terms in which this misconduct was defined in the mid 1980’s—namely, a form of extortion in which your job prospects could be advanced by trading sexual favors. (Harassment in these terms had been recognized and condemned as a social problem for decades, not least in the 1940’s, the age of Rosie the Riveter.) But once harassment was brought into the realm of law, the declared scope of the problem began metastasizing beyond all recognition. Harassment ceased to mean sleazy extortion and became a thoroughly ill-focused term suggesting generalized bias or sexual innuendo in the workplace. Ill-focused, unspecific, and hard to disprove: In short, harassment was lawyers’ heaven.

Phis rhetorical inflation is not unique to sexual relationships. We can .see obvious parallels in the devaluation of the concept of “hate crime” over the last decade or so, from cross-burning to the speaking of bad words and, increasingly, to the expression of unpopular (but nonracist) opinions. How long will it be before it is declared a hate crime to oppose reparations for slavery, or to challenge the propriety of gay marriages? Quite possibly, I suppose, by the time this issue of Chronicles has gone to press.

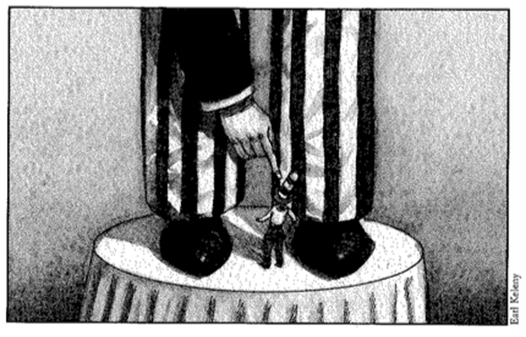

What these diverse examples illustrate is a subtle but perilous shifting of usage that indicates a fundamental change in the concept of government and the state. Interest groups are demanding that the community must intervene to effect certain changes, and that the only acceptable form for this action is legislation by the state. The state, it seems, is the community, the community is the state, and only the state can declare how standards are to be shaped. The notion is dangerous, and not just for the reasons outlined above. At present, it is possible to be an enthusiastic member of the community, of the society, while detesting the government and all its works; in the new formulation, however, to oppose the state and its laws is, perforce, to challenge the community, to reject society. One becomes—to borrow a term from other nations that have explored these concepts in richer detail—an Enemy of the People.

Leave a Reply