In his 1891 novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde writes, “The aim of life is self-development. To realise one’s nature perfectly—that is what each of us is here for … Every impulse that we strive to strangle broods in the mind, and poisons us … Nothing remains then but the recollection of a pleasure, or the luxury of a regret.”

In Wilde’s story, a young man corrupted by thoughts of pleasure and beauty, makes a Faustian bargain and thereby destroys his own life and the lives of many people he encounters. Although it differs in some respects from Wilde’s novel, Albert Lewin’s 1945 eponymous film, is a perfect selection for an October movie night, as it shows the horror of narcissism and an obsession with being godlike in a way that pays homage to Wilde’s creation and offers reflections about mortality are part and parcel of the season.

Hurd Hatfield plays Dorian Gray, a young aristocrat, whose beauty is representative of an ideal. Both men and women find him attractive and engaging, for a variety of reasons, and although he is shy and quiet by nature, Dorian finds he enjoys the attention.

As the film opens, Dorian is posing for a portrait by his friend, Basil Hallward (Lowell Gilmore). In walks Basil’s friend, Lord Henry Wotton (George Sanders), who is there for a visit and becomes fascinated by Dorian. Wotton is a cynic, and he manages to persuade Dorian that the only life worth living is one of pleasure. At this moment, Dorian makes a silent wish: to have his portrait age, but not himself. He is to remain forever young. For this greatest wish of his heart, he is willing to give away his very soul.

Standing in for Goethe’s Mephistopheles in this story is a statue of an Egyptian cat, and it grants Dorian’s wish. But there is a price to be paid for this wish, or rather, there is a reflection projected back into the world of the soul wishing it. If he does not change in his physical appearance, the burgeoning ugliness of his soul must become manifest in some other way. This becomes evident when he breaks off a tender relationship with a tavern singer, Sibyl Vane (Angela Lansbury), who after reading Dorian’s cold letter commits suicide. Dorian then spirals from one evil deed to another. He continues to remain physically the same, yet the world around him changes. His friends are astounded at his apparent youthfulness, yet this magical realism is accepted as a fact. Even so, most become repulsed by the corruption of his soul. Not even years of true friendship can overcome their revulsion at Dorian’s narcissism and utter indifference to human life.

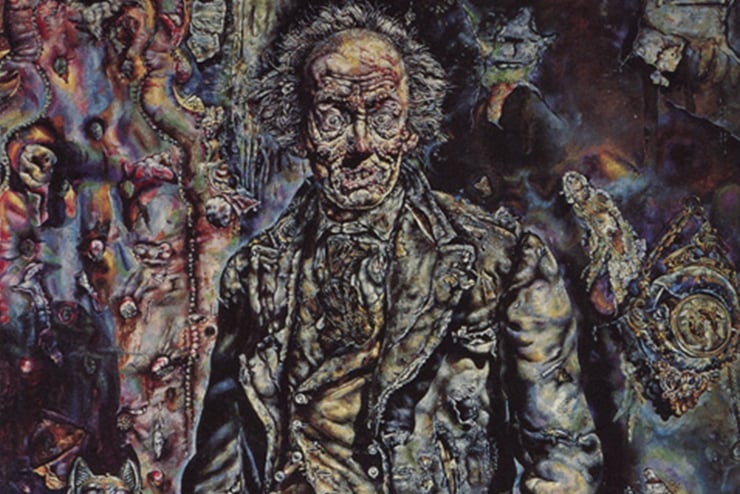

Decades pass and yet Dorian’s facial expression and body are suspended in time. The portrait, however, has been changing. As Dorian commits one evil act after another (including even murder), the young Dorian in the painting becomes a grotesque vision of darkness. His eyes bulge, his face fills with thick and heavy lines, his perfect hair grows into a wormy mess. The painting is the mirror to Dorian’s ugly existence, which looks like a decaying and disfigured body. There is no dignity or beauty here, only painted slopes of evil and one man’s descent into Hell.

To conceal his despicable acts, Dorian hides the portrait, ironically in his childhood room. There, amid the detritus of his forgotten innocence—an old pupil’s desk, wooden blocks, and a bit of embroidery celebrating Dorian’s birth—stands the grand portrait his friend Basil painted so long ago. It is covered because Dorian cannot bear to look at his true self. He shows no remorse for his sins. In fact, as the years go by, he becomes more and more calculating, reveling in the power he has gained over life and death. Nothing can stop him, he thinks, not even God. He is the Übermensch, and the harmless vanity and self-centeredness we witness at the beginning of the film has become this compassionless monstrosity.

Hurd Hatfield’s Dorian is restrained. In the beginning, we read his subdued emotion as a youthful shyness. But Hatfield’s unchanging statuesque expression of absolute void and abyss eventually is unsettling and frightening to look upon. The real horror of Lewin’s film is Dorian’s lack of humanity and personality amid all of the other characters’ reactions to his countenance and life itself. It is precisely this unchangingness that is the horror.

The film is filled with contrasts. As Dorian peels open the layers of depravity and commits evil acts with expressionless indifference, his friends’ reactions become ever more intense. They are fully alive as they face their mortality, whereas Dorian’s only consolation (if such a thing even matters to him) is his security in the knowledge of his immortality and power. He is holds onto it with such fervor, however, that his paradoxical awareness of continuous oblivion is disfiguring his interior life. Can he return to innocence or has his experience taken him into no-man’s land, in which remorse and forgiveness do not exist? The only end is death itself.

By far, the most significant contrast in the film are the two paintings that signify the young Dorian and the evil Dorian (painted for the film by two separate artists). Although the film is shot in black and white and the cinematography creates sharp lines and uneasy shadows reminiscent of Weimar Cinema’s silent classics, the paintings are presented in full color. Thus the contrast between the two personae of Dorian is stark and palpable. This technique gives the theme full effect. The beauty and ugliness, the good and evil, the creation and destruction—all are contained in the small universe called Dorian Gray.

The film is framed by a quote from a poet, Omar Khayyám (1048-1131): “I sent my soul through the invisible,/Some letter of that after-life to spell:/And by and by my soul returned to me,/And answered, ‘I myself am Heaven and Hell’.” Dorian Gray may have been influenced by Lord Wotton’s cynicism about love and marriage, but it was by his own volition that he chose to make a pact with the forces of darkness for the sake of the false light that was his own vanity. Thus, he opened up the “doors of perception” that only led to destruction, without ever truly realizing his own nature or finding his purpose, let alone those of the others once dear to him.

Leave a Reply