This is the first article in a five-part series on Christian Nationalism. Following are links to the other parts: Two, Three, Four, Five.

This issue of Chronicles features a detailed discussion of Christian nationalism and its relevance for contemporary American society. Our discussion presents both defenders and critics of Christian nationalism, together with the views of both its Catholic and Protestant representatives.

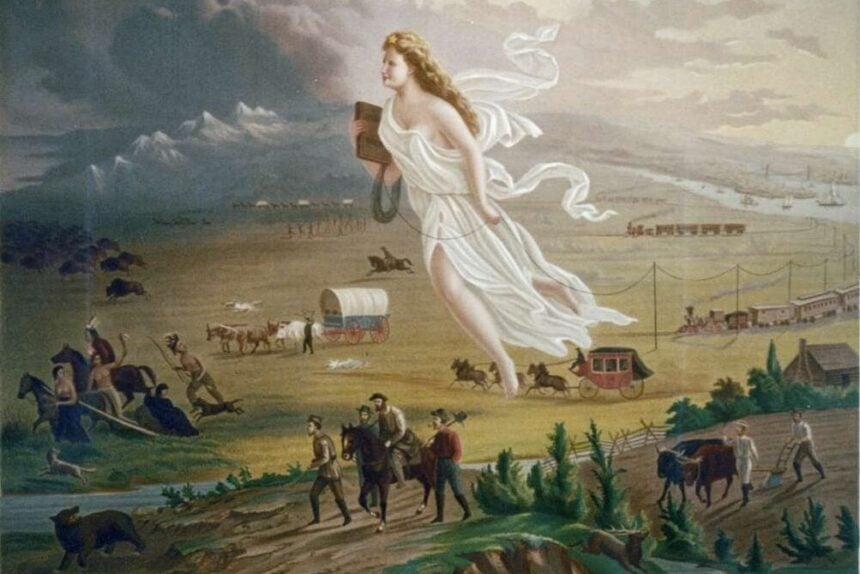

What looks like Christian nationalism can be located far back in the American past and was already discernible in 17th-century New England. Early Protestant settlers in the Massachusetts Bay Colony thought of themselves as executing an “errand into the wilderness.” They believed it was their task to bring biblical truth into what became the New World. Moreover, the “shining city on the hill” that the Puritans saw themselves building was intended to be a model of pious living for the rest of humanity.

As the historian Ernest Lee Tuveson documents in his 1980 book Redeemer Nation, the view that the New World was the setting for a true Christian community became bound up with millenarian themes by the 18th century, an association that continued throughout the next century. Famed Congregationalist theologian and prolific (if not particularly gifted) poet Timothy Dwight left behind a vast body of verse from the 1790s which presents “Columbia” as the recipient of a special grace. In his view, the fledgling America was the fifth kingdom predicted in the Book of Daniel and would soon come into its full glory: “Here the Empire’s last and brightest throne shall rise and peace and Right and Freedom greet the skies.”

Tuveson shows how the theme of America as a divinely chosen land became a dominant homiletic theme in sermons across the country by the early 19th century. By the time America emerged as a victor in the Great War, this providential destiny was turned into a divinely ordained mission to bring light to the entire human race. Sometimes this specifically American mission was given an apocalyptic framework and even treated as a prelude for the return of Christ to an already perfected world. Tuveson also demonstrates how the biblically framed picture of America’s destiny came to incorporate a pro-American reading of the Book of Revelations, in which most of the images in this arcane text were given an America-friendly twist.

What was definitely not interpreted in a friendly manner was the reference to “the Whore of Babylon” in Revelations 17. American Protestant nationalists identified the debauched Kingdom of Babylon with the Roman Church and the prostitute who ruled over this “Abomination” as the pope. Although the once-prevalent view of America as the ultimate Christian nation did not require a demonization of the Catholic Church, the two typically went together, as Protestant Christian nationalists, many of them pastors, whom Tuveson cites, were quick to point out.

It is also the case that many American Christian nationalists, as Walter McDougall, Richard Gamble, Martin Marty and scores of historians have stressed, were also moralizing imperialists. They felt religiously driven to bring “American values” to the rest of the planet, and over time the original Protestant impulse for missionizing was turned into a secular millenarian pursuit to transform humanity. Thus, we see the recasting of religiously motivated “wars for righteousness” into explicitly leftist crusades on behalf of expanding lists of human rights.

In recent months, Congressman Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) has turned this redemptive urge to save humanity in accordance with “our values” into a call for a woke military crusade against the anti-LGBT Babylon that is Vladimir Putin’s Moscow. Although Raskin is not well-disposed toward Christianity and probably abhors the older American nationalism, his obsessions and those of his voters have their distant roots in an American millenarian tradition. The Christian nationalist tradition has given way here to a radically leftist derivation in which the missionary nation remains, but in an obviously distorted form.

There has certainly not been a paucity of severe criticism of Christian nationalism on the right. MacDougall, Gamble, and the foreign relations scholar and Reformed Christian James Kurth have argued that American religious exceptionalism feeds dangerous expansionist tendencies and empty political pride. Such thinkers have characterized American liberal internationalism as a secularized form of religious nationalism and attacked it as morally unseemly and heretical.

Meanwhile, leftist critics of Christian nationalism, like Paul D. Miller and The Dispatch Senior Editor David French, have associated this bête noire with tribalism and racism. Miller, a former adviser to President Obama, has conspicuously warned his fellow Protestants against the exclusionary nature of Christian nationalism. He has even scolded the late historian Samuel Huntington (who was hardly a figure of the right) for praising the Anglo-Saxon Protestant template that engendered American political culture and morality. Although Miller sometimes sounds like conservative critics of Christian nationalism, he is far closer than they to the leftist cultural establishment, which features him as its spokesman for the danger of the religious right.

Unlike Miller, conservative critics are not asked to write about Christian nationalism for fashionable middle- or highbrow magazines; nor are they invited on to TV talk shows to denounce it. With due respect to leftist critics, it is also clear that Christian nationalists today are not racialists of any kind and are delighted to attract Christians of all ethnicities. The reasons that the contemporary left attacks them are obvious: these self-described Christian nationalists vigorously oppose the woke agenda and are mostly found in the flyover country disdained by urban elites.

The populist Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene has described herself repeatedly as a Christian nationalist. This label appeals to her constituents in rural Northern Georgia, who voted for her by an enormous majority. Congresswoman Greene was Catholic, at least until she stopped attending Mass due to priestly sexual abuse scandals, while most of her devoted constituents are Baptists or belong to other low-church Protestant denominations. Greene’s electorate has no trouble sharing the same label with their congresswoman despite denominational differences.

The anti-papist leitmotif of an older Christian nationalism no longer plays any role in this new Christian nationalist alliance. Christian nationalists have evolved from what they were in the American past to become a new movement, and it is quite likely that Greene and her voters have no memory of those earlier divisive associations.

But what is meant by Christian nationalism may not require the classification it has undergone. Unless I’m mistaken, conservative Christians of all denominations and even some non-Christians deplore the social and moral changes that have taken place in the United States and in other Western countries since the 1950s. The banning of prayers composed by instructors in public schools in the Supreme Court’s 1962 Engel v. Vitale decision and the high court’s prohibition of Bible reading and the singing of religious verses in Abington School District v. Schempp in 1963 helped turn the public square into an immaculately secular shrine.

In the 1960s, public schools quickly accelerated this judicially directed trend as the teaching profession moved sharply to the left. In the last 20 years wokeism has replaced nondenominational Christianity or Judeo-Christianity as America’s national religion, and a centralized cultural industry, with its LGBT fixation, has promoted this trend even more obsessively.

The feminist cult of abortion has also played a role in this process of militant antireligiosity, as the Democratic Party and public administration have worked to force all religiously affiliated institutions into supporting what have become unrestricted abortion rights. Even more recently, gender distinctions, which form an integral part of biblical morality, have been under attack, as gender reassignment has become a task that our public schools have begun to promote with enormous enthusiasm.

National Conservatism Conference founder Yoram Hazony has argued that the victory of the woke left signals the failure of the liberal ideology that replaced Christian culture and morality in the U.S. after World War II. Abandoning the older moral and theological foundations of American society, liberal intellectuals convinced their fellow citizens that all first-order questions could or should be settled through “open discussion,” a project that has collapsed in the face of the radical leftist assault upon the notion that the views of the enemy (traditional conservatives) have any legitimacy whatsoever. The agents of wokeism do not “discuss,” they silence.

Unlike Hazony, I have always questioned whether the open society was the real aim of earlier progressives, who claimed to be championing critical discussion but who may have been pursuing a tactic for undermining traditional belief systems. Whatever their intent was, this change in national orientation brought forth in the end a woke subversion, which is causing some of us to question whether the experiment was worth the disaster it caused.

The solution to our moral and social dissolution may be to go back to an older arrangement, which was rescinded in favor of an “open discussion” that was never as open as its classical liberal advocates claimed. That the older classical liberals are now being canceled by wokesters may be just desserts for those who led us astray.

What is less clear is that we should be describing this return to conservative moral foundations as “Christian nationalism.” That concept belongs to a past epoch and may no longer correspond to our historical situation. Instead, we should be speaking about repairing the disastrous mistake of liberalism, which to some extent may still be reparable. We now know that the era of the “open discussion” led to horrible repression and forced moral perversion, and if our society is to free itself from a series of bad decisions, it should try to go back to a situation that existed before the wrong turn was taken.

The Hebrew term “teshuvah,” a word meaning repentance and a return to correct behavior, which appears repeatedly in the prophetic writings, comes to mind here. Repentance should be seen not as turning toward something that is entirely new, but as a return to what the sinner was before he committed the trespass. Although such a going back may be difficult in the present circumstances, self-described Christian nationalists should be focusing on this task.

—Paul Gottfried

Leave a Reply