I remember the day I stopped playing with toys as a kid. A small collection of G.I. Joes would usually occupy my afternoons. I would stage ambushes, march them along my windowsill and over the peaks of pillows, subjecting them to all the perils mustered by a boy’s imagination. Then, one day, whatever we call the thing that lives in children and animates this sort of play, went out like a candle in the wind. In my hands were lumps of plastic, cold and silent, nothing more. There might even have been a twinge of embarrassment upon the sudden realization. I had grown up. Well, sort of.

An inevitable part of fatherhood (and I am a relatively new father) is revisiting your childhood, whether you like it or not. The fairy tales of the past return to regale and encode our children as they did us. We teach our kids how to play by playing with them. We stoke the embers of their imaginations by imagining with them.

Sometimes, it feels childish. There is that twinge of embarrassment again. Adults have important things to do, and as we so often hear, we live in times of great political import. But perhaps we are wrong to feel embarrassed and to give in to the pull of more “important” things. Perhaps this is the reason so many adults end up dastards and dullards.

C. S. Lewis may have agreed. In his essay, “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” Lewis wrote, “Critics who treat ‘adult’ as a term of approval, instead of as merely a descriptive term, cannot be adult themselves.” Ironically, the preoccupation with being perceived as an adult is a mark of childhood and adolescence. America has managed to become a country of childlike grown-ups with stunted imaginations—the worst combination of each state of life.

Thus, we get the mindless grasping at childish things now permeating our culture. Witness the rise of people who proudly identify as DINKs, or “dual income, no kids.” Typically, they proclaim their status by boasting on social media about all the things they can do whenever they want to because they are not “burdened” with the responsibilities of having kids. They present themselves as permanent adolescents with a lot more money and time to spend on themselves.

“We don’t have kids to feed, but we’ve got lots of money to spend on goodies,” says one woman in a TikTok video with more than 1.5 million “likes.” She and her husband are in their early 30s, and the video shows them filling their Costco shopping cart with more than $250 worth of groceries, mainly junk food.

Fashion houses such as Gucci have begun selling $4,500 purses in the shape of Mickey Mouse’s head because plenty of adults will buy them. Marvel Cinematic Universe films are larded with paper-thin superheroes and CGI that does more to disengage our brains than enliven our imaginations. Each blockbuster is, to borrow from Shakespeare, “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Our wardrobes, which increasingly resemble the onesies and play clothes infants wear, also demonstrate the problem. It’s even in the kidspeak we use daily.

In short, in our fear of being shamed for humbling ourselves and becoming “like little children” in our wonder at creation, as Jesus admonished us to do in Matthew 18, we have instead become childlike in all the ways that matter least and are unworthy of us. It is a bizarre phenomenon. A nation of civilized children who lack the moral imagination of youth. You’d think a people like this would manage to be happier than we are, given how little we appear to need to take seriously. Yet anxiety and depression are on the rise. Ironically, our clinging to the “things” of youth deprives us of every worthwhile aspect of true youthfulness.

Even the young grow old before their time. That might be because social media hasn’t just allowed us to connect faster; it has made us “grow up” faster by giving kids front-row seats to war, politics, sex, and the brutalities of everyday life. As Lewis wrote, they are encouraged to desire the “approval” of adults and to be adults themselves at earlier and earlier stages of their lives. Social media platforms need to turn a profit, and they have located a lucrative market in the insecurities of children and adults alike.

A new Harvard study found that in 2022, platforms like Snapchat, TikTok, and YouTube collectively generated $11 billion in revenue from advertising that targeted children and teenagers. That figure includes nearly $2 billion in profits from users 12 and under. The data these companies harvest leads kids down rabbit holes, and down there they aren’t finding either Alice or Wonderland. The authors note at the outset that a “growing body of research documents associations between social media use, social media advertising, and negative mental health outcomes among youth, including depression, anxiety, and eating disorders.”

That’s too bad for boys and girls, according to S. Bryn Austin, one of the authors of the Harvard study and a professor of social and behavioral sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Although social media platforms may claim that they can self-regulate their practices to reduce the harms to young people, they have yet to do so, and our study suggests they have overwhelming financial incentives to continue to delay taking meaningful steps to protect children,” Austin told CBS News. Like Bram Stoker’s Dracula, social media is a vampire that preys on the innocent, leaving it marked, drained, and enthralled. No wonder youth suicide rates increased 62 percent between 2007—the year the first iPhone was released—and 2021.

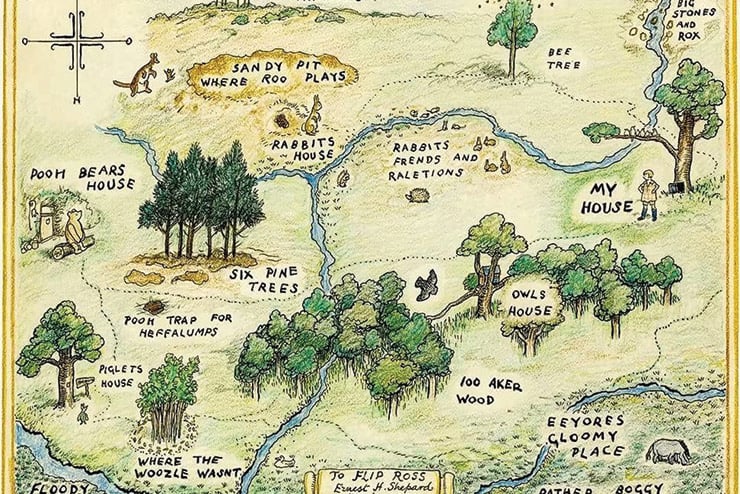

That’s what happens when society rushes kids out of the Hundred Acre Wood and onto the Interstate 405. Does Winnie-the-Pooh seem like too childish a reference for a Chronicles column?

Consider that A. A. Milne served in the British Army in World War I. The Arcadian world Milne constructed, hidden away in the Hundred Acre Wood, was supposed to be free from the sorts of horrors he saw on the Western Front, where Milne’s best friend, Ernest Pusch, died during the Somme offensive. “Just as he was settling down to his tea, a shell came over and blew him to pieces,” Milne recounted. A sniper killed Pusch’s brother Frederick just a few days later.

Milne intended The Hundred Acre Wood to be free from the ordinary restraints of adulthood, from the fear of the finality of death. He named our honey-loving friend after a teddy bear owned by his son, Christopher Robin Milne, and you can guess which character the boy inspired. Pooh and friends were Milne’s answer to W. B. Yeats in “The Stolen Child,” in which the poet wrote:

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

It’s no surprise that stunted children become stunted adults, combining the realms of adulthood and childhood while ruining both in the confusion. But these things are meant to be separate, each introduced in its own proper time. Smashing them together closes the door to the kingdom of awe that comes with being a child, where our imaginations are intended to be singularly free. It’s a place we can and should revisit in adulthood, but it is not supposed to be mistaken for reality. Ecclesiastes tells us:

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever. The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose. The wind goeth toward the south, and turneth about unto the north; it whirleth about continually, and the wind returneth again according to his circuits. All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.

There is a season for everything, a proper time and place. The DINK adults who want to live forever in a dull, suspended version of childhood end up getting the worst of both worlds. Real adults, however, can enjoy occasionally revisiting youthful passions without shame, because they have embraced the responsibilities of adulthood.

Lewis picked up on this. “When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so,” he wrote. “Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.”

It’s a childish thing to be afraid of being seen as childish. Before I became a father, I felt the same way. But now I have children of my own and I see how they are able to find grandeur all around them. I do my best to join them as I try to keep them in their own Hundred Acre Wood for as long as possible, where “the waters and the wild” will be waiting for them when it is their time to return. ◆

Leave a Reply