In the Introduction to Walker Percy Remembered, David Horace Harwell explains that he began his project with the idea of writing a conventional biography of Percy, one that would explore some fresh aspect of the novelist’s life. Then, as the research unfolded, he “found the form that best suits Percy.” The result is what Harwell calls a “community biography,” a collection of interviews with Percy’s friends, acquaintances, and family members. A “community biography” strikes me as a suspect notion. If one assumes that a biography is an attempt, however inevitably flawed, to write a coherent account of a person’s life, then it is difficult to see how a miscellany of interviews, even when conducted by the same interviewer, can amount to a biography, communal or otherwise. Moreover, Harwell’s approach works at cross purposes. On the one hand, he attempts to bring some thematic coherence to most of these 13 interviews by focusing his questions especially on Percy’s involvement in the community of Covington, the Louisiana town on the north shore of Lake Pont-char-train where he lived for the final decades of his life. On the other, Harwell gives his interviewees free rein to ramble on at length about anything they please—which, more often than not, turns out to be themselves. Thus, Harwell’s attempts to maintain thematic continuity are frequently thwarted by the garrulousness of some of his subjects. That said, I hasten to add that, however misleading the concept, Harwell’s “community biography” is not without interest and would no doubt have amused Dr. Percy himself, who was, as Harwell notes, “a man who lived for just such conversations.”

Percy lived in Covington with his family for over 30 years and died there in 1990. In his 1980 Esquire essay “Why I Live Where I Live,” Percy claimed to have moved his family to Covington because it was the perfect “nonplace” for him—just far enough from his Greenville, Mississippi, upbringing to keep the ancestral ghosts at bay, yet within shouting distance of the Big Easy, a city oozing with a sense of place. Of Covington, Percy wrote,

It had no country clubs, no subdivisions, no Chamber of Commerce, no hospitals, no psychiatrists . . . I didn’t know anybody, had no kin [there]. A stranger in my own country. A perfect place for a writer!

Indeed, Percy wrote five of his six novels in Covington, not to mention a number of first-rate philosophical essays and the whimsical Lost in the Cosmos. Yet Percy did not remain a stranger there. As Jay Tolson’s 1992 biography of Percy, Pilgrim in the Ruins, reveals, and as Harwell’s collection of interviews amply confirms, Percy was—contrary to expectation, perhaps—very much a part of his community. He was an active member of the Community Relations Council of Greater Covington, a biracial group of citizens who worked to improve employment and housing conditions for blacks; he was enthusiastic about the local Head Start program, even volunteering to drive a Head Start bus; he was a key figure in organizing a credit union for poor blacks; he was involved in his local parish and served on the school board at St. Scholastica’s, a Catholic girls’ high school; and he was active in a number of reading groups, both in Covington and in New Orleans.

In these interviews, Harwell is particularly intent on highlighting Percy’s involvement in civil-rights issues during the turbulent 1960’s, but very little is revealed that has not already been covered in the standard biographies. Certainly, it is well known that, on racial matters at least, Percy was a JFK liberal in those years and worked hard to oppose the influence of the Ku Klux Klan in the Covington area. When Harwell asks Nikki Barringer, a Covington attorney and a good friend of Percy’s, about the novelist’s civil-rights work, Barringer notes, among other things, that Percy became involved in a Confederate-flag dispute after some black students in the local high school became “incensed” that the flag was being displayed in the office of the school’s principal, Louis Wagner. After the students filed suit to have the flag removed, Percy was called to testify. According to Barringer, Percy testified “that he was a person knowledgeable in the business of icons . . . and that, yes, indeed, this sort of thing would incite children in the school to aggressive behavior.” In fact, the Tolson biography covers this incident in more detail; there, we learn that, after the U.S. district court in New Orleans ruled that the flag was a provocation and would have to be removed, the Percy family received bomb threats from the local Klan and spent two weeks sleeping in the attic of their house. Since Tolson says nothing about how Percy came to be called as a witness in the first place, one would have thought that Harwell might attempt to probe attorney Barringer’s memory for some illuminating background detail, but he fails to do so. I was left wondering whether the protest and subsequent legal action had been organized by the students themselves, or whether the NAACP (or some other group of activists) had been involved. Harwell also passes up a wonderful opportunity to ask how Percy’s ideas about the Confederate flag might have changed over the years. For example, did he, in the 1980’s, years after the Klan’s power had been successfully crushed, still believe the flag’s symbolism to be hopelessly tainted by racist associations? And how did Percy view the rise of the affirmative-action culture of the 1970’s and 80’s? Did he feel that the work of the civil-rights movement was genuinely furthered by racial quotas? Harwell never asks such questions, though a number of the interviewees in this book would no doubt have been able to provide some insight.

Another line of inquiry that Harwell pursues involves Percy’s commitment to the Catholic Church. James Boulware, described by Harwell as “a former priest at [Covington’s] St. Joseph Abbey,” makes the somewhat controversial claim in the book’s opening interview that Percy “was never comfortable as a Catholic,” that he was “still Protestant, but he saw through the kind of thin veil that you find in Protestantism, and he saw the richness of the Catholic church.” Percy attended Mass at St. Joseph’s for many years as one of Boulware’s parishioners; we might assume, then, that Boulware had some pastoral reason for questioning the depth of Percy’s commitment to Catholicism. However, he offers nothing substantial in evidence. In Boulware’s opinion, Percy the philosopher always had the upper hand over Percy the man of faith:

I don’t think he ever found something that was completely convincing for him. He just kept peeling the onion, trying to move further and further to the core of something, and I don’t think he ever found it.

Whatever truth there may be in such claims, it is curious that Harwell never asks Boulware why he left the priesthood (in 1979), thus depriving the reader of the kind of perspective that would allow him to make a more informed judgment about the validity of this renegade priest’s claims. It is undoubtedly the case that Percy, according to Tolson and others, suffered a crisis of faith in the 1970’s, but he reaffirmed that faith in subsequent years and, by most accounts, remained a staunchly traditional Catholic to the end.

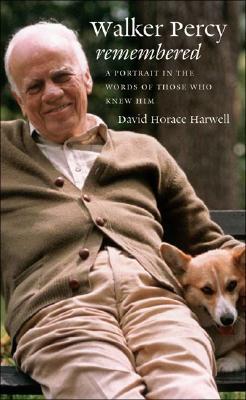

While Walker Percy Remembered adds little of substance to our biographical knowledge of Percy, it succeeds in several of these interviews in placing Percy firmly within the Covington milieu, largely through an accumulation of minor but revealing detail. We learn from Judy La-Cour, a teacher at St. Paul’s School in Covington in the 1970’s and 80’s, that Percy frequently visited her high-school English classes (at her invitation) and spoke enthusiastically with the students there about the questions raised in his novels, and that the school now annually honors its outstanding English student by adding his or her name to a plaque that features a picture of Percy and his dog, Sweet Thing. We learn from Lee Barrios, who typed Percy’s manuscripts for several years and who describes herself as having been “heavy-duty into the Bible” in those days, that he was particularly concerned that his novels might offend her. Shyly, and sometimes stuttering, he would tap on the door of the room where she worked in the Percy house and ask, “Lee, having any problems?” or say, “Well, I hope you’re not embarrassed by any of the characters in there.” From Carrie Cyprian, the Percy’s black housekeeper and cook, we discover that Dr. Percy once repaired one of her Thanksgiving turkeys with his surgical kit and that he loved her fried liver smothered in onions and her squash pie. Cyprian also talks about an occasion when Percy’s dog turned up missing. When her husband found the dog and returned it, Percy gave him a signed copy of The Last Gentleman, a novel that Cyprian never read and twice calls Gentleman, Gentleman.

Ironically, the most entertaining of the interviews with Covington locals is the one from which we learn the least about Percy himself. Harwell interviewed John “Red” Smith, tradesman and raconteur, at his family hardware business in downtown Covington. Smith provides a wealth of anecdotal information about the 19th-century origins of Covington, its commercial history, and its more recent transformation into a bedroom community for commuters who work in New Orleans.

I tell you what, though, they got some people coming over from New Orleans now, and they’re bringing New Orleans over here. . . . They come over here, and they say, “This is the way we did it in New Orleans.” Well, why in the hell did they leave New Orleans?

Asked how well the people of the town knew Percy, Smith says, “He never associated too much with my type of person because I ain’t an intellectual. He was, and he’d associate with the Friends of the Library, people of that nature.” Later in the interview, however, Smith admits that Percy invited him to the house on several occasions, though he never did pay a visit. He claims that, before Percy’s death, he didn’t even know that Percy wrote books. “The only thing I know about him, is that he called Covington a ‘non-place,’” Smith adds. “I wasn’t quite sure why he stayed here because a ‘non-place,’ in my definition, would be an undesirable place. So why’d he come over here to a non-place to live?”

Given his intention of providing a portrait of Percy’s life and community involvement in Covington, it is unfortunate that Harwell did not interview more Covingtonites of “Red” Smith’s ilk. It is notable that only 8 of these 13 interviewees are (or were) Covington residents. The five remaining interviews, all clustered in the second half of the book, offer precious little insight into Percy’s life in the town. These include lengthy interviews with “bootleg preacher” and longtime friend of Percy, Will Campbell; Shelby Foote; and Phin Percy, Walker’s youngest brother; as well as somewhat shorter conversations with LeRoy Percy (another brother) and Rhoda Faust, owner of the Maple Street Book Shop in New Orleans. And while all of these interviews provide some valuable details about Percy’s relationship, for example, with his revered Greenville uncle, William Alexander Percy (who reared the Percy brothers after the deaths of their parents), or about Percy’s literary influences, one has to wade through a good deal of irrelevant material to find out those details. I, for one, am not particularly interested in Campbell’s friendship with country singer Waylon Jennings or his childhood as a dirt-poor Baptist in Amite County, Mississippi. Similarly, Shelby Foote’s legendary loquacity is here, as elsewhere, merely tedious at times, though he is occasionally interesting on literary matters. He notes, for example, that, from childhood (Foote and Percy became friends when both were still adolescents in Greenville), he had always been “a great champion of Tolstoy,” while Percy was a diehard defender of Dostoyevsky. Foote loved to “infuriate [Percy] by saying that Dostoevsky was the greatest slick writer that ever lived,” and claims that, decades later, Percy admitted, “You were right about Dostoevsky.” Sadly, however, we never learn just why Foote thought Dostoyevsky a “slick writer” or why Percy came to agree. Harwell simply fails to pursue the matter.

Students of Percy’s life and work will no doubt find Walker Percy Remembered a welcome, if somewhat redundant, addition to their bookshelves. It is clearly a labor of love and respect, and for that reason alone I wish that I could give it a more wholehearted endorsement. On the whole, this “community biography” does, by fits and starts, manage “to flesh out the character of [Percy] in the context of his community, his closest friends, and his family” (though Percy’s widow, Bunt, chose not to be interviewed). I do wish, though, that Harwell had done a little less “muting of the authorial voice” and had intervened a little more often and a touch more aggressively during the course of these interviews.

[Walker Percy Remembered: A Portrait in the Words of Those Who Knew Him, by David Horace Harwell (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press) 200 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply