The first thing I did when I became president of the Motion Picture Association of America was to junk the Hays Production Code.” Jack Valenti eliminated the Hays Production Code in 1966—when the average weekly motion-picture audience in the United States was 38 million people. The very next year, with the “moral strictures” of the old code gone and the infectious “new” ideas of the counterculture seeping into Hollywood, the weekly average fell to 17 million. Less than half. It was the most astonishing one-year decline in motion-picture history.

And the industry has never recovered its lost audience. As recently as 1991, the weekly average was still only 18 million (and any seemingly impressive box office receipts are really the result of a ticket-price inflation of nearly 70 percent over the past ten years). What happened? Everyone knows what happened, but three-time Oscar winner Frank Capra, who retired in disgust from the business in the late 60’s, describes it with gusto in his autobiography The Name Above the Title (197]):

The winds of change blew through the dream factories of make-believe. . . . The hedonists, the homosexuals, the hemophilic bleeding hearts, the God-haters, the quick-buck artists who substituted shock for talent, all cried: “Shake ’em! Rattle ’em! God is dead. . . . Shock! To hell with the good in man. Dredge up his evil—shock! Shock!”

And yet, amazing as it seems, things have actually gotten far worse than they were in the late 1960’s.

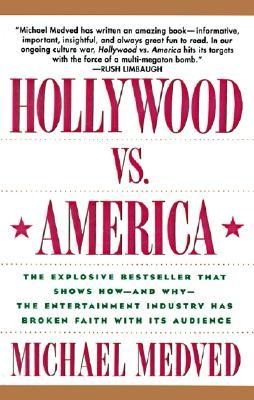

In his excellent and courageous new book, Hollywood vs. America, Michael Medved, co-host of PBS’s Sneak Previews, analyzes both the extent of the problem and the reason why things went wrong. Regarding the latter, he describes the core of the industry as a small community of insecure professionals who want, more than anything else, to be “taken seriously” and considered as “artists.” Generally uninformed about the arts, they eagerly bought into the 60’s revival of that old, simpleminded, and quite boring Jacobin notion that the “real” artist continually shocks and irritates the bourgeoisie. This led to a natural antipathy and arrogance toward the ideals of middle-class America—their potential audience.

For example, in his chapter entitled “The Glorification of Ugliness,” Medved discusses Hollywood’s most recent obsessions: cannibalism (at least 11 films in the past four years), urine (17 recent examples), and vomit (one could even compare the vomiting techniques of Meryl Streep, Sissy Spacek, and Pave Dunaway). Medved also prepares his readers for the forthcoming big-budget film Sacred Cows, in which the President of the United States somehow has sex with a barnyard bovine.

More fundamental aspects of the problem that are analyzed by Medved, with both depth and countless examples, arc Hollywood’s relentless assaults on religion and the traditional family, its exaltation of promiscuity (and even illegitimacy), its addiction to violence and obscenity, its antipathy to heroes, and its constant bashing of the United States. Concerning this last issue, Medved writes of the absurdly revisionist Dances with Wolves: “By converting these Sioux Indians into gentle, vaguely pacifist, environmentally responsible bucolics, Kevin Costner, in a state of holy empty-headedness, has falsified history as much as any time-serving Stalinist of the Red Decade.”

The motion-picture industry, of course, defiantly rejects such criticism. Everything it docs is either a “reflection” of society (an argument that Medved effectively demolishes) or simply a form of entertainment with no real impact on its viewers. Thus the same people who relentlessly drop gratuitous environmental “messages” into their films in order to “save the earth” will, at the same time, deny that The Deer Hunter’s premier on national television had anything to do with the 26 people who, in subsequent weeks, killed themselves playing Russian roulette. Medved is particularly effective in destroying the lingering myth that “no one really knows” whether film and television violence affects the viewing audience. As he discusses in detail, “more than three thousand research projects and scientific studies between 1960 and 1992 have confirmed the correlation between a steady diet of violent entertainment and aggressive and antisocial behavior.”

So what can be done? Michael Medved doesn’t believe that either federal censorship or a resurrected production code would work in today’s diversified Hollywood. He docs feel that boycotts and lobbying groups can be particularly effective. And he also believes that “movieland missionaries” of traditional Christian or Jewish beliefs can greatly affect the industry by offering a viable and fulfilling response to “the spiritual hunger” of many Hollywood professionals—a “hunger” that is frequently wasted on Scientology, Shirley MacLaine-type idiocy, or the latest industry fad; Marianne Williamson’s “Course in Miracles.”

[Hollywood vs. America: Popular Culture and the War Against Traditional Values, by Michael Medved (New York: HarperCollins) 288 pp., $20.00]

Leave a Reply