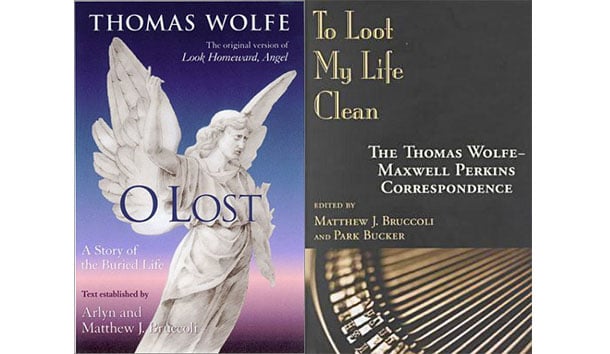

What we have here are two good books published by the increasingly adventurous University of South Carolina Press in celebration of the centenary of Thomas Wolfe (1900-1938). O Lost is the original version of what became Look Homeward, Angel (1929), the text being carefully established and edited by Arlyn and Matthew J. Bruccoli from a pencil draft in 17 ledgers, a typescript carbon copy (with a few missing pages), and five clusters of the ribbon copy. The editors tell us that “The setting copy of Look Homeward, Angel is unlocated and presumed lost.” The job of composing an accurate text—a labor of love by the editors who have foregone any earnings and royalties in favor of the Wolfe estate—was more complicated than it might have been since neither Wolfe nor his famous editor. Maxwell Perkins, nor his typist, Abe Smith, troubled themselves very much with small details. Most of the line editing and proofreading and correction for Scribner’s was accomplished by poet-editor John Hall Wheelock. A few months after publication of Angel, Wolfe received a letter from Louis N. Feipel, whose hobby was proofreading published books and who sent Wolfe a list of hundreds of errors and inconsistencies. According to the editors, none of these errors and inconsistencies in Angel was ever emended. The scholarship is solid, and the strategy of the editors direct. “The rationale for this edition is to establish the text of O Lost that should have been published in 1929 by Charles Scribner’s Sons after necessary editing, house styling and proofing.”

To Loot My Life Clean: The Thomas Wolfe-Maxwell Perkins Correspondence, published simultaneously with O Lost, is what it announces itself to he and something more. It offers some 251 letters exchanged between Wolfe and Perkins, John Hall Wheelock, Charles Scribner, III, and others at Scribner’s, roughly two thirds of which have never been published. The letters are presented chronologically from the March 1928 “Note For the Publisher’s Reader,” written before Wolfe first made contact with Perkins, to Perkins’ final telegram to Fred Wolfe on the occasion of Tom’s death—”Deeply sorry . . . ” In addition to useful notes, there are five appendices—”Undatable Letters,” “Unmailed Wolfe Letters,” “Maxwell Perkins’ Biographical Observations on Thomas Wolfe,” “Errors and Inconsistencies in the Published Text of Look Homeward, Angel,” and “Scribner’s Alteration Lists for Of Time and the River.” Taken together, these two books, among other things, definitively dispel the popular myth that, somehow or other, Wolfe was an invention of Maxwell Perkins. As Bruccoli and Bucker put it,

According to the popular version of this story, Wolfe was an undisciplined writer whose exuberant, overwritten prose could only be published through a collaboration with his editor. Perkins is portrayed as a controlling editor-father to Wolfe, the child-writer, from whom words flowed unhindered and unexamined. . . . The letters published here document Wolfe’s artistic and professional problems and demonstrate how Perkins, as both editor and friend, aided Wolfe in solving them. They set the record straight.

Perkins, who worked with a variety of well-known writers — Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Caroline Gordon, Nancy Hale, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings among them—seems to have concerned himself chiefly with questions of structure and point of view. Thus, the fundamental differences between O Lost and Angel are structural and depend on limiting the point of view, as much as possible, to the consciousness of the protagonist, Eugene Gant. O Lost was clearly intended by Wolfe to be a much more inclusive and omniscient narrative. Certainly the book, though composed of much of the same autobiographical materials as Angel and Of Time and the River, is a different novel and one well worth the expense and effort of resurrection. Whether or not it is, as the editors assert, a “better” novel than Look Homeward, Angel is a judgment call: It all depends. What is certain, though, is that, as a first novel by a new and unknown writer, it would not likely have been published by Scribner’s (or anyone else) except in some kind of cut and rearranged form. Not that O Lost was, by any serious standards, too long or too experimental. Once Look Homeward, Angel had been published and had achieved considerable commercial and critical success, length and size were less of a problem, as witness the next novel—Of Time and the River.

In combination, O Lost and To Loot My Life Clean serve to answer some longstanding questions, even as they raise others. After them, Wolfe has to be taken as demonstrably a more assured craftsman, possessed of a larger and more complex vision than he has usually been considered to have had. Perkins was uniformly helpful and sympathetic, especially in the making of Of Time and the River, but Wolfe was always his own man. “Real life” was somewhat more complicated, however. Driven by a fierce hunger for fame (something more than “celebrity”), Wolfe was often difficult and disingenuous; often, in Perkins’ word, “turbulent.” Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, his presence on the Scribner’s back list ultimately earned the publisher a fortune. Wolfe, however, had serious money problems: Scribner’s was considerate, but niggardly. With full appreciation of the venture of the University of South Carolina Press, one must wonder if the present-day Scribner’s were not the appropriate publisher of these books. We are also left wondering why it took so long for all this to matter—that is, why Wolfe’s literary reputation suffered after his untimely death and in spite of his undeniable achievement. The Perkins myth, overturned by these books, is part of it. So is politics. The 1950’s version of political correctness was, if anything, even more obnoxiously obstreperous than the current one.

Finally, there is the aesthetic factor. Though Wolfe was much admired by readers and many other writers, he was an original, a romantic, not easily to be understood or honored by modernist and postmodernist critics. Nevertheless, his works have remained in print and his influence on three generations of American writers seems undiminished.

[O Lost: A Story of the Buried Life, by Thomas Wolfe, Text established by Arlyn and Matthew ]. Bruccoli (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press) 736 pp., $29.95]

[To Loot My Life Clean: The Thomas Wolfe-Maxwell Perkins Correspondence, Edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli and Park Backer (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press) 340 pp.. $39.95]

Leave a Reply