The historical record shows that election fraud is as American as apple pie. The divided America of today is in a situation similar to the one it found itself in during one of its most corrupt elections, the presidential election of 1876—except worse.

The myth of American exceptionalism is the most powerful and lasting of all our national myths. It absorbs and assimilates all the others, including the counter-myths that have periodically challenged it. But there are facts that this national myth cannot assimilate, cannot reconcile, cannot acknowledge to be true—therefore, these facts cannot be spoken.

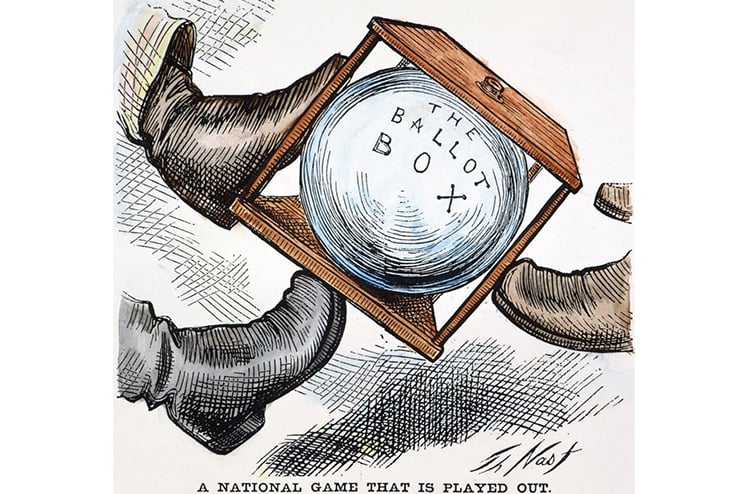

One of these facts is that cheating has been a recurring part of the American electoral process. “Election integrity” is rhetorical point of pride among politicians in our great shining city on a hill, a beacon radiating the principles of liberal democratic governance upon the world’s backward dictatorships. That elections may in fact be corrupt in the heart of the world’s greatest democracy touches what Thomas Merton called “the unspeakable.”

On a Sunday morning early in 2021 I heard my pastor say, “We have had contested elections before.” His were among the few words I ever heard spoken in my church about the 2020 presidential election. Given the calming, reassuring tone in which he delivered them, and the larger context of the sermon, I took his meaning to be something like this: we have been through bitter, angry post-election fights before, but have always emerged from them just as we were before, or maybe even better, with no real damage done to our body politic or constitutional order. We even had a post-election civil war. If we got through that, surely we will get through this—whatever this may be.

Recounting in narrative form what actually happened in the past, and how it happened, is the work of the historian. How difficult that can be is shown in the not only conflicting but absolutely contradictory contemporary versions about what happened before, during, and after the presidential election of 2020. If the people who lived through an event cannot agree about what happened, how can an historian living decades or centuries later ascertain the truth? And how can our country move forward when Americans strongly disagree on the facts of this recent history?

Think about what my pastor did not say, but could have said, as it is historically true, and highly relevant to our predicament: “We have had stolen elections before.” Perhaps he did not know that stolen elections in America are an historical certainty, or perhaps he did not want to suggest or imply that the 2020 election may have been stolen, too. Acknowledging that would offend the collective social entity which Plato metaphorically named “the Great Beast.”

All American presidential elections have been contested except for the first, in 1789, and the ninth, in 1820. In the ninth, President James Monroe ran for reelection and won 231 out of 235 electoral votes (with three abstentions and one dissenting vote for John Quincy Adams). That election is evidence of an organic national unity that is now as extinct as the western frontier.

America has also had at least two stolen presidential elections, as well as one that was almost stolen in 1800, and one in 1860 whose outcome was rejected by half the country, leading to a four-year civil war and a geopolitical division that persists to this day. That America “survived” this civil war depends on the meaning of the verb, and ignores the obvious implication that what happened once can happen again.

One of the stolen elections happened in 1960. Two Democrat political machines, one in Texas the other in Illinois, manufactured just enough votes to decide a close election in favor of John F. Kennedy. The closeness of the vote likely made it easier to steal. The healthier and less corrupt a country is—and 1960s America was certainly healthier and less corrupt that 2020s America—the narrower the vote must be to swing an election using illicit means.

How close was it? Kennedy won the popular vote by only 118,000 votes out of 68 million cast. Nixon won 26 states, Kennedy 23. Kennedy won the Electoral College and the presidency by a vote of 303 to 219. Shift Illinois and Texas to Nixon, and Nixon would have won by 270 to 252. That Nixon did actually win those states is the judgment of Seymour Hersh in his 1997 book The Dark Side of Camelot. Chicago was run by Democratic Mayor Richard Daly’s political machine and the mob. The two working together had no trouble inserting enough Kennedy ballots ward-by-ward to give him the victory in the state. Joe Kennedy made a deal to help get his son elected, as he had done in the past. After his reelection to the Senate in 1958, JFK even joked about his father’s influence at the Gridiron Club:

I have just received the following wire from my

generous daddy: “Dear Jack—Don’t buy a single vote more than necessary—I’ll be damned if I am going to pay for a landslide.”

Did it in the end really matter which of the two young World War II veterans was elected? Kennedy was a Cold War liberal, but so was Nixon. The New Left despised Kennedy as a right-wing Democrat and playboy, as David Horowitz recounts in his brilliant memoir, Radical Son. Kennedy was no radical, and Nixon was no reactionary. Had the vice president been elected instead of the senator from Massachusetts, one can easily see him signing civil rights legislation essentially the same as that signed by Kennedy’s replacement, Johnson. A reelected Nixon would probably also have gone along with something similar to the “war on poverty” launched by Johnson, though perhaps one resulting in a slightly less expensive welfare state. And one can envision Nixon losing his nerve and canceling the air strikes and Marine landings necessary to save the CIA’s exile army and regime-change operation in Cuba, just as Kennedy did.

In short, the theft of the 1960 election was more about Kennedy family ambition, political cronyism, and urban political corruption than anything ideological, treasonous, or malevolent.

The other definitively stolen election, in 1876, is worth examining in detail, both for the tactics used and for purposes of comparison with the situation in 2020. The 1876 election was about what a party in power will do to stay in power—especially when it is convinced that it deserves to do so. This time it was the Republicans who stole it. Just two years before, the Republicans had suffered one of the worst defeats in a congressional election in American history. They had lost 85 House seats, and the Democrats gained 77; what had been a 102-seat Republican majority became a 60-seat minority. They still had the Senate, having lost only four seats, but that body had been designed to resist such populist waves. In addition, the Grant administration was wracked by scandal, the country was still reeling from the Panic of 1873, and the passions of the war (the Republicans’ biggest political asset) had cooled. In short, the Republicans went into the election with a weak hand, and most observers expected the Democrats to win the presidency for the first time since 1856.

Yet the Republicans won the election with a bold plan to disenfranchise white voters in three Southern states that were still under military occupation 11 years after the war: Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. In that year, both parties ran governors for president, Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio for the Republicans and Samuel J. Tilden of New York for the Democrats.

By midnight of election day, Tilden looked to everyone to have won. He had a popular vote majority of 250,000 and 184 out of the 185 votes needed to win the Electoral College. He had won four Northern states: Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Indiana. In addition, he had a narrow lead in Oregon and comfortable leads in South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. All he needed to secure his victory was to carry one of those four states. Democrats began celebrating, and the chairman of the Republican Party, Zachariah Chandler, retired to his hotel room with a bottle of whisky.

But some Republicans were made of sterner stuff, General Daniel Sickles for example. A Tammany Hall Democrat before the war who as late as 1860 insisted that secession was a constitutional right of all the states, Sickles was rewarded with an officer’s commission by President Lincoln after switching parties in 1861, and was now high in Republican circles. While Chandler was sleeping it off, Sickles arrived at Republican headquarters and hatched a plan. He would send telegrams to Republican leaders in the four states, three of them governors, not to concede the election. Then he would go to The New York Times, a paper which functioned politically then exactly as it does today, except for rather than against the Republican Party, and get its editors ready to promote the narrative of a contested election. Finally, he would send delegations of Republican leaders, lawyers, and bags of greenbacks to New Orleans and the three Southern capitols—Columbia, Tallahassee, Baton Rouge—to oversee election audits.

The strategy Sickles chose for challenging the legitimacy of the result was an obvious one. His bagmen would allege that white Democrats intimidated freedmen to keep them from voting, which was grounds under reconstruction law for canceling an equal number of white votes. The Oregon Republicans could take care of the vote themselves. After they woke Zachariah Chandler from his stupor and got him to sign off on it, they went to work. The first edition of The New York Times accordingly declared the new reality: “A Doubtful Election.” The second morning edition proclaimed not only Oregon but South Carolina and Louisiana for Hayes.

The exercise of power depends upon efficacy and will, but both rest upon that intangible but real phenomenon known as legitimacy, or what famed military historian Basil Liddell Hart called “the moral factor.” In other words, whether the exercise of power is seen as legitimate in the eyes of those being acted upon. As they worked out their plan to steal the 1876 election, Sickles and Chandler knew that their party still controlled all the levers of power and the trappings of legitimacy necessary: the Supreme Court, the White House, the Senate, and, most importantly, the state canvassing boards in the three Southern states.

Today’s Democratic Party seems to have come to a similar calculation. With effective control of the Senate, the Justice Department, the security agencies, the military high command, most of the federal judiciary, and all of the corporate consensus media, the Democrats have even more political power and the opinion-shaping tools at their disposal than did the Republicans of 1876.

Despite losing their congressional election two years before, the Republicans of 1876 were able to act one last time under the narrative that they were the victors who had won the Civil War, who saved the union, who freed the slaves—and who got rich doing it. Of course the Democrats saw things differently: The Republicans were the party that had provoked an unnecessary war and won it by exercising unconstitutional powers. They then forged a unitary republic out of the ruins of the confederation of states created by the Founders, which they had wrecked and overthrown.

On Dec. 6, 1876, the Electoral College convened in all the states but could not come to a decision, for there were two sets of election returns and two sets of electors from the four disputed states. Prior to the convocation, Louisiana’s Returning Board threw out 13,250 Tilden votes and certified Hayes the victor. South Carolina’s and Florida’s Canvassing Boards did the same.

It was up to Congress to resolve the dispute, just as it had been in 1801, when a contingent election had to be held to resolve a tie the year before. Jefferson was voted into the presidency on a tally of ten states to five and had been the clear choice of the nation, with overwhelming support from every part of country except New England. Tilden was also the clear choice in 1876, if less convincingly so, and he too faced his strongest opposition in New England, the moralistic, fanatical center of American Yankeedom.

How do we know which candidate really won those states in 1876? There are only two ways of forming a judgment. One is to go to the primary sources directly, though they are hard to find and may no longer exist. The other is to rely on our predecessors, closer to the event, better read in the primary sources, with broader and more detailed knowledge. These older historians may be just as

authoritative as primary sources, provided their authority is based on sound judgment.

James Ford Rhodes was to the second half of the 19th century what George Bancroft was to the first: America’s leading historian. Rhodes was a Northerner and yet believed the 1876 election to have been stolen from Tilden. He chronicled the Republicans’ fraud in volume 7 (1896) of his magisterial History of the United States.

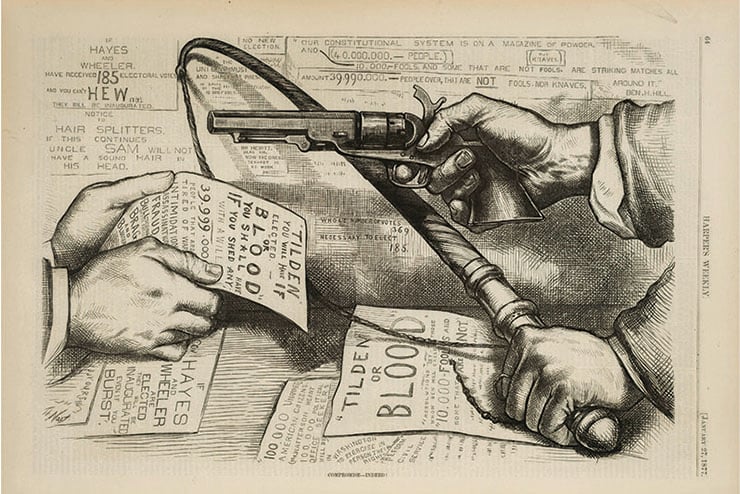

Primary sources recorded at the time of the 1876 election also show that every Democrat in the country, and even many Republicans, such as the historian Charles Francis Adams, believed the Republicans were in the process of stealing it. Northern Democrats held protest meetings and shouted, “Tilden or Blood!

(Massachusetts Historical Society)

This level of vehement opposition was still allowed to exist in 1876, unlike in the current day, when the Democratic Party exercises near-total control over America’s opinion-shaping media, which allows it to treat all opposition to itself as dangerous extremism and its own extremism as moderation itself. Given their hysterics over Donald Trump, imagine how America’s mainstream media and security services would react if Trump voters had held signs at the Jan. 6, 2021, protests at the Capitol that read, “Trump or Blood!”

That was not the case in 1876, when the Republicans could not simply demonize the opinions of the opposing party in the media, but had to act with the appearance of legitimacy.

The more radical Republican faction, who had been the leaders and bulwark of the party since 1860, urged a more brutal exercise of raw power. They believed that when Congress convened in January to ratify the Electoral College vote, the Republican president pro tempore of the Senate, Thomas W. Ferry, should simply ignore the Tilden electors from the four contested states and only count the Hayes ones. The House would object, but what could it do?

For the first time, more conservative and pragmatic Republicans took charge of the situation. If they were going to steal the election, they had to cover the crime in a cloak of legitimacy; there was no other way than to secure Democrat support for the final result. To that end, they created a bipartisan electoral commission to decide who won the disputed states. It was the perfect device for the Republicans to legitimize their fraud and also served as a face-saving device that would allow the Democrats to accept defeat. How successful the creation of this commission was for the political purposes of both parties is evident in that more Democrats voted for its creation than Republicans. TheRepublican stalwarts, with the unreasoning stupidity typical of fanatics, voted against the commission. The bill creating the commission passed the House on Jan. 26, by 191 votes to 86; Grant signed it into law on Jan. 29.

The Electoral Commission would have 15 members: five senators (3 Republican, 2 Democrat), five representatives (3 Democrat, 2 Republican), and five Supreme Court justices (3 Republican, 2 Democrat). The Democrats expected, or at least hoped, that the deciding vote (everyone expected partisanship to prevail), would be Justice David Davis of Illinois, who although a Republican appointed to the bench by President Lincoln, would render an independent judgment. The Republicans were taking no chances, and dashed the Democrats’ hope when, immediately after the creation of the commission, the Illinois legislature elected Davis to the United States Senate, and Davis resigned from the Court.

Davis’s successor, Justice Joseph P. Bradley of New Jersey, initially seemed like a fair-minded replacement, as he was also a moderate Republican who had written an opinion that the commission was obligated “to go behind the returns” in the disputed states. In other words, he planned to examine the evidence behind the claims made by Democratic attorneys that the Republicans had fabricated affidavits alleging widespread voter disenfranchisement by white Democrats. The irony behind the Republicans’ affidavits, of course, is that it actually was they who were disenfranchising Southern white Democrat voters.

But the right people whispered in Bradley’s ear, namely, Senator Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen and Secretary of the Navy George M. Robeson, both New Jersey Republican politicians and friends of Bradley, and he voted with the other Republicans not to investigate the disputed returns. Gore Vidal, who told the history of the election in his book 1876: A Novel, describes Bradley as wearing a perpetual half-smile, just like our own John Roberts, who similarly failed the country during the 2020 election. On Feb. 10, Bradley voted with the other Republicans to award Florida’s electors to Hayes; Louisiana followed on Feb. 16, Oregon on Feb. 23, and South Carolina on Feb. 28. In each case, both houses of Congress voted to accept the commission’s opinion and accept the Hayes’ electors, giving him 185 electoral votes to Tilden’s 184.

It remains the closest Electoral College result in American history. On March 2, the President of the Senate declared Rutherford B. Hayes the duly elected president of the United States.

Three days later Hayes was inaugurated on the steps of the Capitol, surrounded by federal troops. The troops were there to quell a potential rebellion. As Vidal puts it, “Daily the nation is reminded that the Democratic Party having once gone into rebellion might do so again.” The fear of a renewal of hostilities is in part why the Democratic Speaker of the House, Samuel J. Randall of Pennsylvania, voted with the majority to accept Hayes’ presidency and the fig-leaf of the electoral commission, as did the majority of Southern Democrats in the House. For Hayes’ part, he was no radical, and tried to govern in a way that would appease the Democrats. Though he was sarcastically referred to as “His Fraudulency,” unlike America’s current fraudulent president, his purpose was not to betray but to conciliate his country.

To secure Southern support, Hayes made three promises, all of which he kept: He would appoint a Southerner to his cabinet, David Key of Tennessee, who became Postmaster General; he would support federal funding for Southern infrastructure projects; and, most important, he would withdraw federal troops from Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana.

Louisiana had installed a Democratic governor in January. With the troops gone, and the Republican canvassing boards dissolved, Florida and South Carolina followed. And so, as the newspaper editor and historian Claude Bowers put it, “the South was free again to rule herself.” Thus did the Republicans cede military and political control of the three states they had used to steal the election, ensuring that they could not do it a second time.

No such concessions were made by the Biden Democrats to the MAGA Republicans after the November 2020 election. On the contrary, Democrats began the ongoing harassment and prosecution of those who alleged electoral fraud. As an added perversity, the Democrats’ silent junior partners, the establishment Republicans, likely helped to steal the Arizona gubernatorial election in the fall of 2022 from the Trump-endorsed candidate, Kari Lake. In a choice between a left-wing Democrat and an America First Republican, Arizona’s Republican machine saw the Democrat as the lesser evil. The victorious Democrat in that state, Katie Hobbs, refused to debate Lake and barely even campaigned. Yet she won. Among those elected in a near-Democratic sweep of high statewide offices was Adrian Fontes, a former lawyer who had represented clients the FBI alleged were affiliated with Mexican cartels. Fontes is now the Arizona secretary of state who will supervise and administer the state’s 2024 presidential election results and, with the new Democratic governor, certify the result.

Every empire that has ever existed always ends the same: by conquering the people who created it.

Toward the end of 1876, Vidal has his main character, Charlie Schuyler, ask the poet and newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant, “How have things managed to go so wrong with us?” Bryant’s answer is immediate, “The war.” One hundred and forty-four years later, is that not the same answer to the same question?

Every empire that has ever existed always ends the same: by conquering the people who created it. The American empire may be in terminal decline and increasingly an international joke, but its domestic administrative apparatus retains its absolute hold on power. To do so, it has had to rely upon force and fraud in equal and increasing measure. What succeeded the Cold War abroad was a cold civil war at home, interrupted only briefly by the amorphous war on “terror,” whose object is now domestic opposition to the empire. The election of 2020 is best understood in the context of the suppression of internal dissent within a dying empire. And while America has been through stolen elections before, we have not been through this before.

Leave a Reply