Our editor’s article on the 100th anniversary of the “March on Rome” focuses on the welcome boldness of the celebrants of Il Duce in Predappio, who, he writes, were “defending a nation than has been around for thousands of years, one which has produced a towering national culture and which is now struggling against the globalists and wokesters, who wish to put an end to all European national identities.”

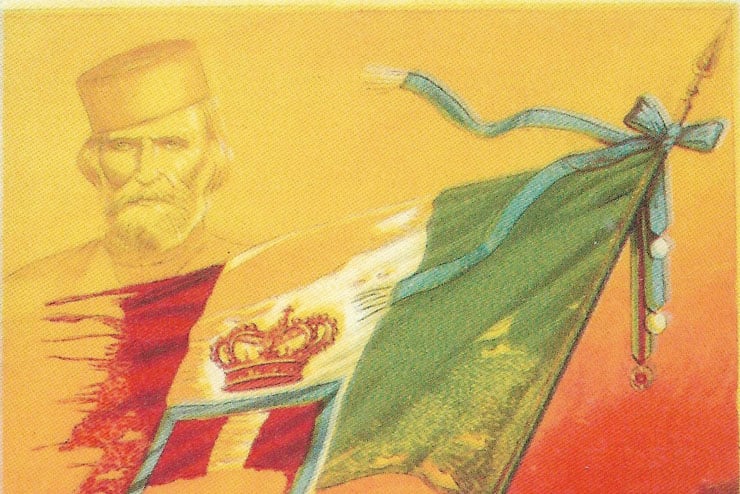

I agree with the drift of Prof. Gottfried’s argument. Resisting the assault on European identities and culture is, indeed, a worthy endeavor. But there is a problem with his premise of the existence of the Italian identity and nationhood. It most assuredly has not been around “for thousands of years” in any recognizable form. The establishment of the unified Italian state nearly two centuries ago was followed by a concerted attempt to forge one—by hook more than by crook—in the name of a Jacobin concept of “the Nation,” as desired by Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, two unpleasant characters and anticlerical Freemasons to boot.

To them and their followers, “Italy” was an imagined community—a horrid term which is in this case unfortunately applicable—whose creation entailed violent suppression of centuries-long identities and loyalties in Naples, Calabria, and Sicily (in which “Italia” was assumed among the unwashed to be the name of the Savoyan king’s wife). The endeavor was aided by the British Royal Navy, for geopolitical reasons that had nothing to do with the well-being and happiness of the people thus Italianized.

It is a little-known fact that Italian immigrants in Argentina in the late 19th century, where they vastly outnumbered those from Spain, quickly learned Spanish. They used Spanish to communicate not only with the state and municipal authorities but also to talk to other Italian immigrants from the Apennines. This was the easiest way to overcome the impossibility of the natives of Sicily or Calabria understanding their neighbors and fellow workers from Trentino or Veneto. Their descendants, generals Leopoldo Galtieri and Roberto Viola, commanded the Malvinas (Falklands) war in 1982

There has been a culture of the geographic term known as “Italy” for thousands of years, indeed, but the secularist concept calling itself “the Italian nation” remains moot to this day. My prematurely departed friend Alessandro Mussolino, a member of the legislative council of Veneto, once told me a joke: “Why was Sicily awarded the Nobel Peace Prize? Because it’s the only Arab country never to declare war on Israel!” To Alessandro, and to thousands of his constituents and fellow Northern Italians, Palermo or Reggio di Calabria are more foreign, today, than the Swiss Lugano or the French Nice.

Mussolini was a volunteer in the Great War, but it was—for many Southern Italians—a slaughter in which the haughty Piamontese officers ordered their despised southern recruits into fruitless attacks against the Austrians on the Piave and proved their ineptitude at the disaster of Caporetto in 1917. They died obediently—Italy lost half a million men to no visible avail—but they refused to fight meaningfully in North Africa or at Stalingrad, under Il Duce, a generation later. They surrendered en masse in Ethiopia, in Libya, and in the East. Not because they were cowards, but because they did not believe in Mussolini’s idea of the neo-Roman Italianità.

Authentic European nations—such as Hungarians, Poles, Greeks, Serbs and others, mainly in the East—steeped in the collective memory and culture, united by blood and sentiment, inspired by their glorious defeats which were turned into lasting victories (Mohacs, Kosovo), can and should defend themselves against the globalists and wokesters.

Italy is not one of them. Its putative nationhood rests on flawed foundations. Its political scene is a mess, as witnessed by the false-flag patriot Giorgia Meloni, yet another false promise of rebirth and renewal. Its political class is rotten to the core.

Italy is a wonderful, civilized European country, one in which I would like to spend my twilight years—but it is not a nation.

Leave a Reply