For the nearly four decades that I have had the privilege of writing for Chronicles, I have consistently berated the Supreme Court for abandoning the original understanding of the Constitution. The Court has indulged, in effect, in rewriting America’s founding document to find a constitutional protection for abortion, to misread the First Amendment to prohibit religion in the public square, and to undercut the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause in order to permit preferential treatment of some Americans on the basis of race.

In the past few years, culminating in these last two Supreme Court terms, and as a direct result of Donald Trump’s appointments, the Court has begun, finally, to recapture the Constitution by reversing some of its past mistakes. Most notably, in the 5-4 decision last term in the Dobbs case, to the surprise of many of us, the Court flat-out confessed error in Roe v. Wade, ruling that there was nothing in the Constitution about abortion and that the states were free to determine for themselves whether or not to permit that practice. Other decisions in the last few terms have given increased protection to those professing religious objections to mandatory governmental policies protecting purported LGBTQ rights, to those seeking to pray at public functions, and to those seeking to recognize the historical Judeo-Christian roots of the American polity.

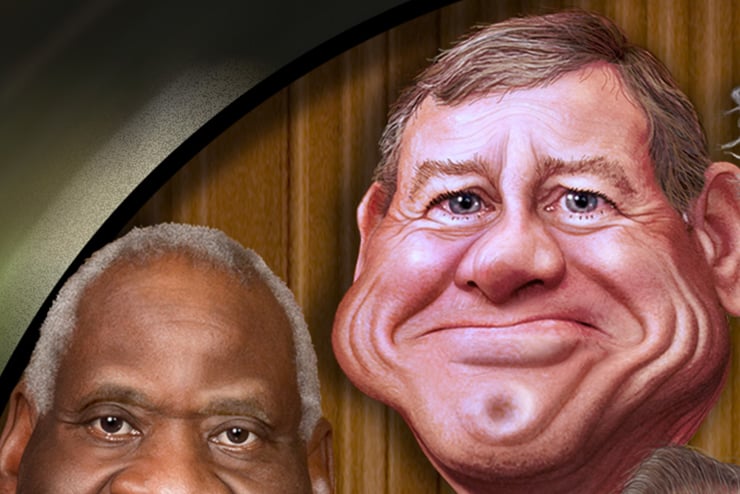

Finally, this term, the Court, in a 6-3 decision written by Chief Justice John Roberts, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, has ruled that neither public nor private universities may make admissions decisions based solely on the race of the applicant. In the course of this decision, the Court ruled against the admissions policies of Harvard and the University of North Carolina, which policies were plainly implemented in order to maintain, over many years, a balance of admitted students from different races. The effect of this policy, clearly demonstrated in the case, was to make it much harder for Asian and white students to be admitted to those universities while facilitating the admission of black and Hispanic applicants. Asians and whites needed higher standardized scores and GPAs to be admitted to universities than did blacks and Hispanics.

In ringing words, in what could be his greatest opinion on the Court, Roberts wrote that the Constitution has a “pledge of racial equality,” and that the “core purpose” of the Equal Protection Clause was “doing away with all governmentally imposed discrimination based on race.” Thus, he concluded, North Carolina’s and Harvard’s preferential admissions for racial minorities and stricter standards for other races were unconstitutional. Some progressives, including some of the dissenting justices, bewailed the decision as a betrayal of deserving minorities and as an abandonment on the part of the Court of America’s national commitment to justice and “equity” for previously-discriminated-against groups.

Unfortunately, the Court’s opinion left a gigantic loophole that allows college admissions officers to continue to do precisely what Roberts’s opinion expressly condemned. In language that was immediately seized upon by the very Harvard administrators the Court had ostensibly ruled against, Roberts wrote,

Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.

Roberts’ ameliorative language all but implies that America has been riven with systemic racism and that a student’s efforts to overcome that might well gain preferential admissions. If this was not affirmative action under slightly different terms, it’s difficult to know what else it could have been. Unfortunately, this uncertainty, indecision, and slipperiness is an all-too-common trait of this chief justice, who appears to see himself as a moderate “institutionalist,” who pulls his punches, lest he plunge the Court into the kind of maelstrom it was in in the aftermath of Bush v. Gore.

The result of Students for Fair Admissions, rather than ending counting by race is likely to be increased litigation and unpredictability as admissions officers, through such tactics as abandoning standardized tests and requiring Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity statements (of a kind that Roberts seems to invite by his language) unashamedly try to maintain the racial balance the Court ostensibly seeks to condemn. It is not clear that much university administrative behavior is likely actually to change.

The outstanding failure of Roberts’s opinion was its lack of a clear rejection of the “diversity” rationale for affirmative action. There was at least a sparkling dissent by the Court’s conscience, Justice Clarence Thomas, who did ridicule the current dogma of diversity. “The solution to our Nation’s racial problems thus cannot come from policies grounded in affirmative action or some other conception of equity,” Thomas wrote. “Racialism,” he added, “simply cannot be undone by different or more racialism.”

There is, then, some reason to hope that the conservative majority of the Court will continue with the project of restoring the Constitution, and surely the broad condemnation of counting by race ought to be an indication that reparations plans can never pass Constitutional muster. Nevertheless, it is the good faith of college administrators and government officials that is required to maintain adherence to the rule of law—and that appears to be in short supply in our trying times.

Leave a Reply